Understanding Power Transmission Financing

Search

Please fill the input to search

The group of authors who donated their expertise (and time!) to this book came together for a simple and collective intent: to address the critical deficit of transmission capacity in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is stated that roughly half the population of Sub-Saharan Africa (or 600 million people) lack reliable access to electricity. The lack of electricity access is particularly stark at a time when the global number of persons without access to electricity is falling.

While there is no adequate information on the breakdown between generation, transmission, and distribution, historically investment in generation has been roughly four times higher than transmission and distribution combined. Furthermore, the distribution sector has also attracted more investment than transmission, leaving this segment of the African energy market as the most impacted by a lack of both public and private investment.

The critical nature of transmission infrastructure to the overall function of an energy market cannot be overstated. As generation expands, transmission is needed to bring electricity to the demand centres. Additional transmission capacity (including cross-border) can also provide access to large power generation sources and connect them to unserved demand. Transmission across national borders, often referred to as interconnection, enables economies of scale that bring down the cost of power and allow for greater efficiency in matching production with consumption.

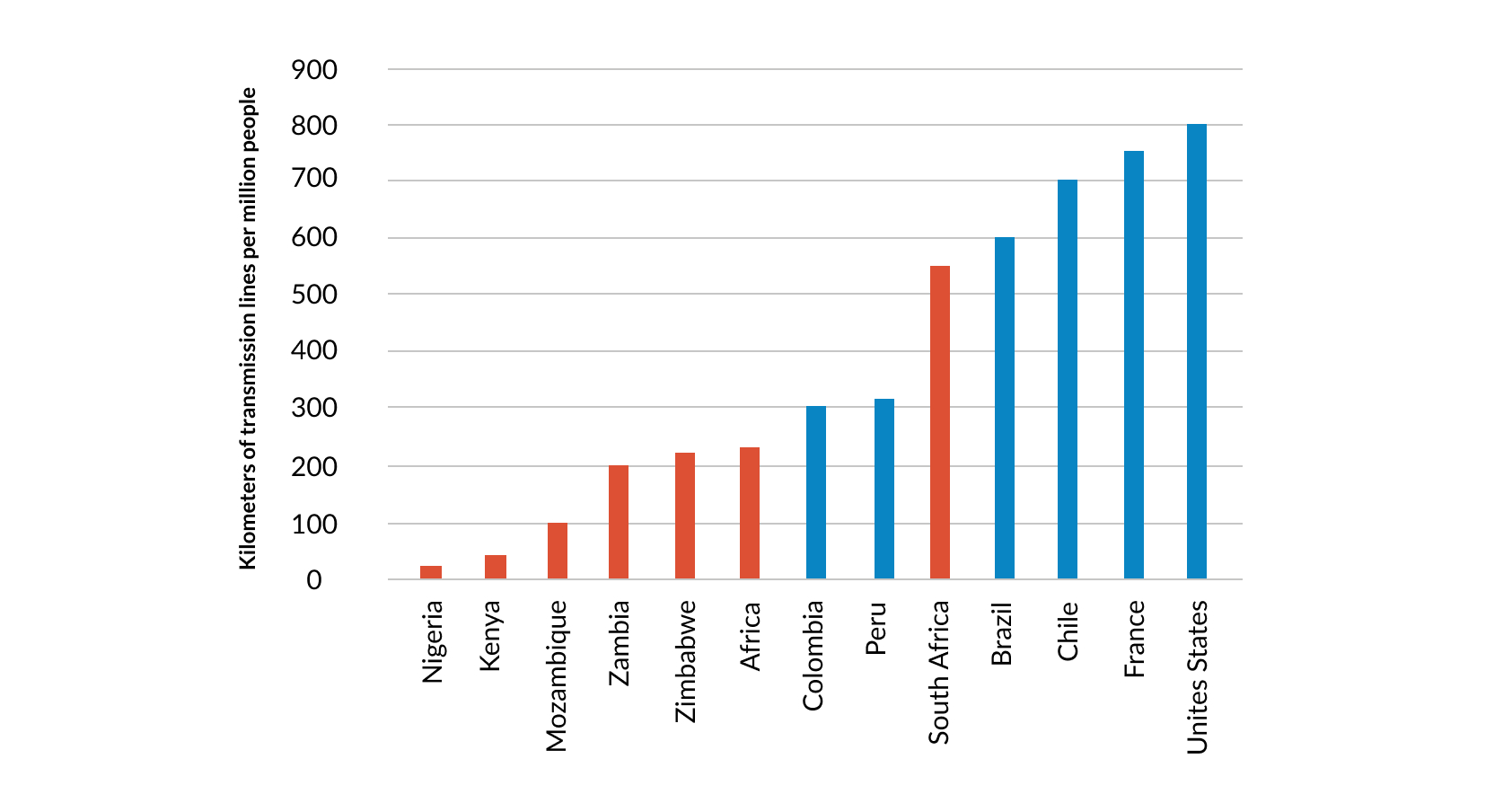

Current estimates place the total investment requirements for the period 2014-2040 at $80-$140 billion, which equates to $3.2–$5.4 billion per year. Of the 38 Sub-Saharan African countries, 9 have no transmission lines above 100 kilovolts (kV). The scale of the transmission deficit is also significant when one considers that the combined length of transmission in the 38 Sub-Saharan African countries is about 112,196 km, less than the length of the domestic transmission network of Brazil. The following Figure 1.1 helps further illustrate the transmission deficit in Sub-Saharan Africa as compared to energy markets around the world.

At a time when the world is coming together to address the threat of climate change, it is also important to note that transmission infrastructure is essential to the transition towards a less carbon-intensive power market. Without it, many grid-connected utility-scale renewable energy projects cannot be implemented. More importantly, developing and maintaining highly optimised transmission systems that can manage the intermittent nature of renewable energy helps to reduce technical losses and avoid the need to build additional generation or storage capacity.

The critical lack of development of transmission infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa, despite the increased investment in other segments of the power value chain, naturally leads to two important questions: How did the situation become so dire? and how can we overcome the transmission deficit to widen the access to energy? The first question demands an intense inquiry into economics, politics, sociology and geography that is beyond the capacity of the authors of this handbook. The second question, however, can be answered constructively and is the focus of this book.

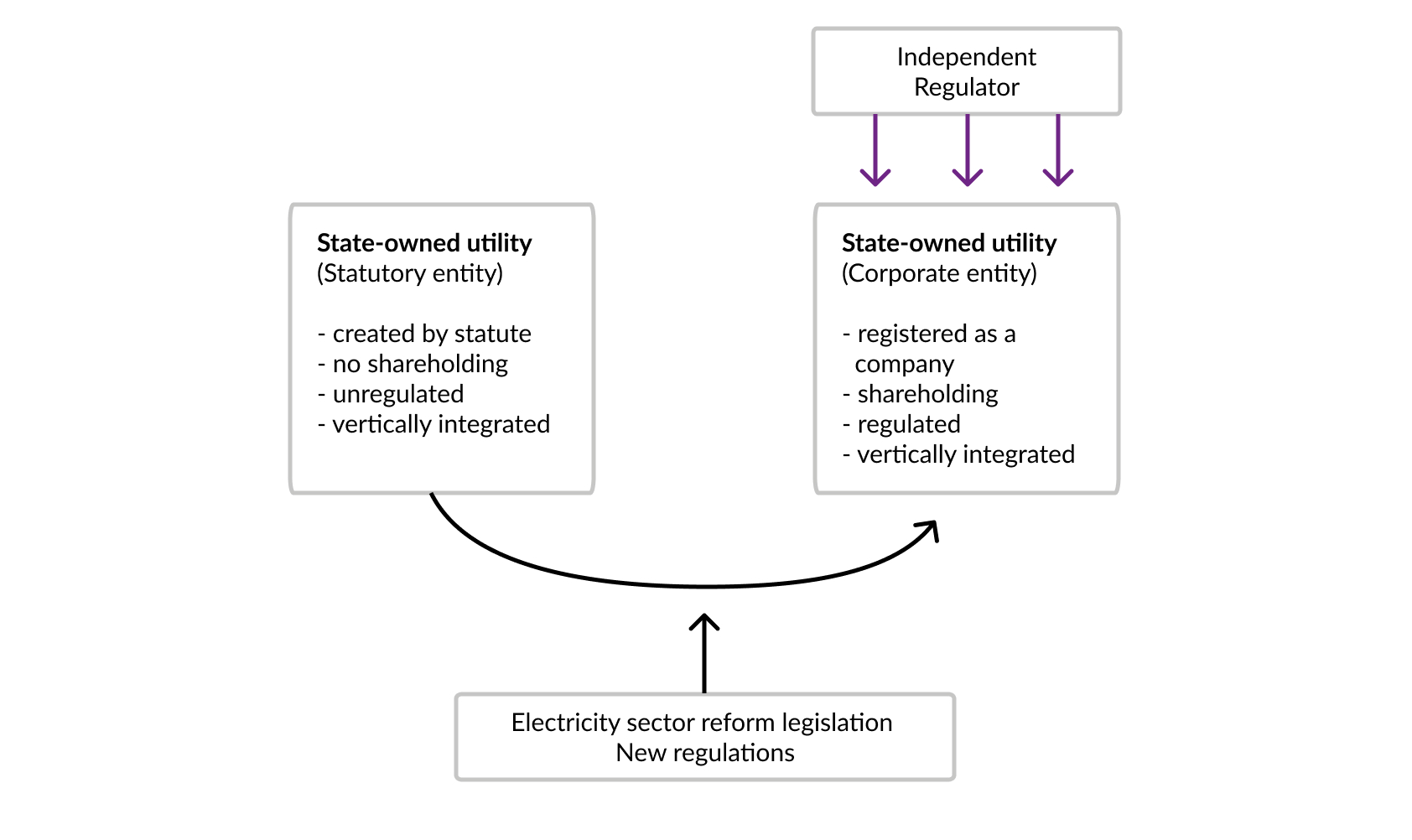

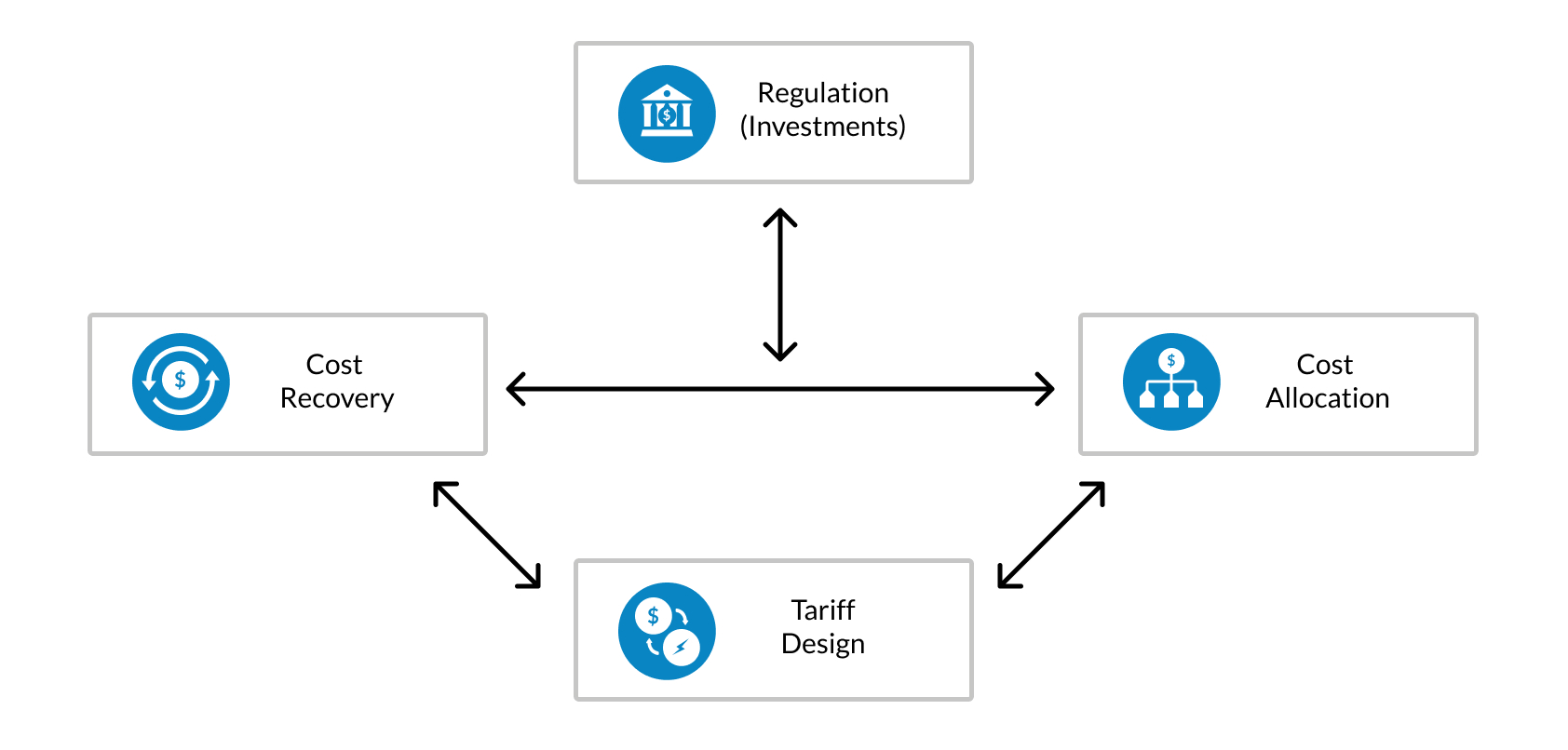

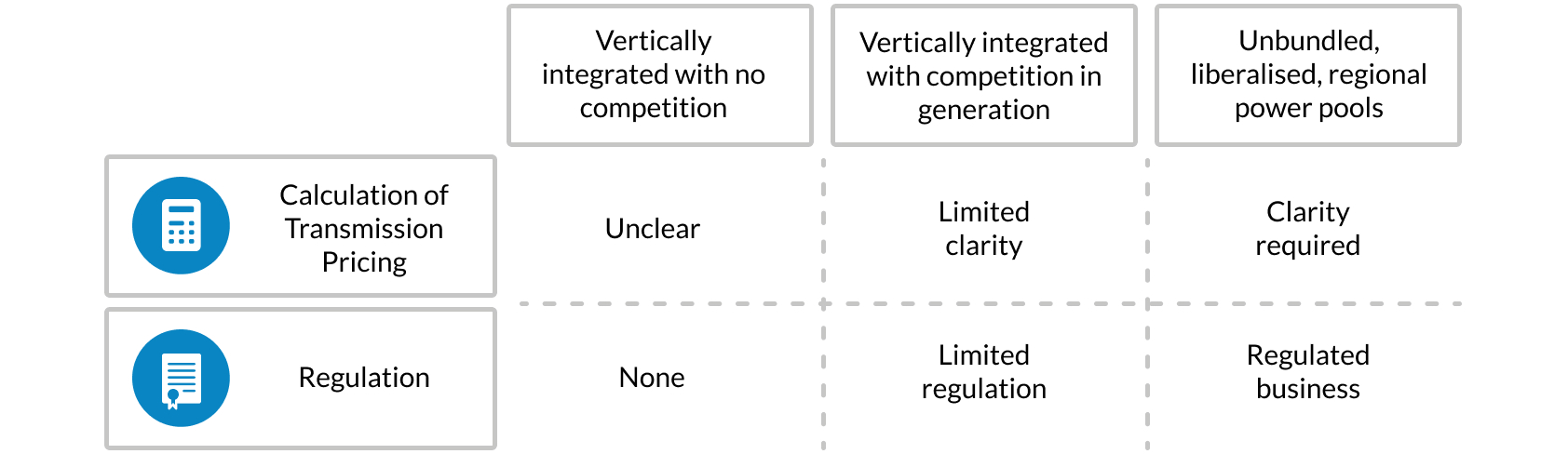

Virtually all development of transmission infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa remains within the responsibility of fully or partially state-owned utilities. One reason is that it is difficult to prioritise and justify transmission projects when transmission costs are not clear and transparently allocated within the sector. As a result, the utilities that currently manage transmission infrastructure often require public subsidies to counter operating losses that arise when costs are not properly allocated and recouped. These subsidies usually take the form of direct budget support from the government. The effect is that state-owned utilities are not incentivised or able to invest in new projects.

This vicious circle of generating losses and failing to invest in new infrastructure is not inevitable. There are numerous examples around the world where energy markets have been able to overcome this transmission deficit through a combination of concerted regulatory reform and partnership with the private sector. This book presents these examples as case studies distributed throughout the chapters. The common narrative across the experiences from other markets is as follows: if the existing market actors (government, utility, regulator) can bring clarity and predictability to the transmission sector, the private sector can deploy its expertise and capital to overcome the infrastructure gap.

It is important to note at the outset of this book that the primary constraint on private investment is not the lack of the availability of capital (see chapter 2. Financing Structures and Capital Sources). The key constraint is, rather, the ability to access that funding through market regulations and project structures that provide the predictable operating conditions and revenue that are fundamental to any commercial investment. This book is intended to outline how public officials can satisfy these expectations from the private sector through a general description of transmission sector regulation, planning and operation, and a detailed explanation of the structures for private investment in the transmission sector.

As previously noted, the existing transmission gap in Sub-Saharan Africa is driven in large part by the inability to fund new infrastructure through public budgets or finance public infrastructure due to a history of operating losses. Thus, the first motivating factor for using private capital to fund transmission infrastructure is to mobilise finance over and above what the public sector may be able to provide. The private sector is not, however, simply a source of capital. It is also a partner in project management, cost control and risk mitigation. With the appropriate set of incentives, the private sector can be an extremely efficient implementation model for transmission projects at a low cost and on schedule. Successful private transmission projects have been implemented in India, Latin America, the Philippines, United Kingdom, and elsewhere. Brazil alone has financed over 50,000 km of transmission lines through private investments.

Inviting private investment in the transmission sector can also bring innovation through the utilisation of state-of-the-art technologies which are transforming the energy landscape. For example, smart grid technologie introduce new capabilities and provide opportunities for more efficiency, as well as new services (energy management, distributed generation, internet and telecoms).

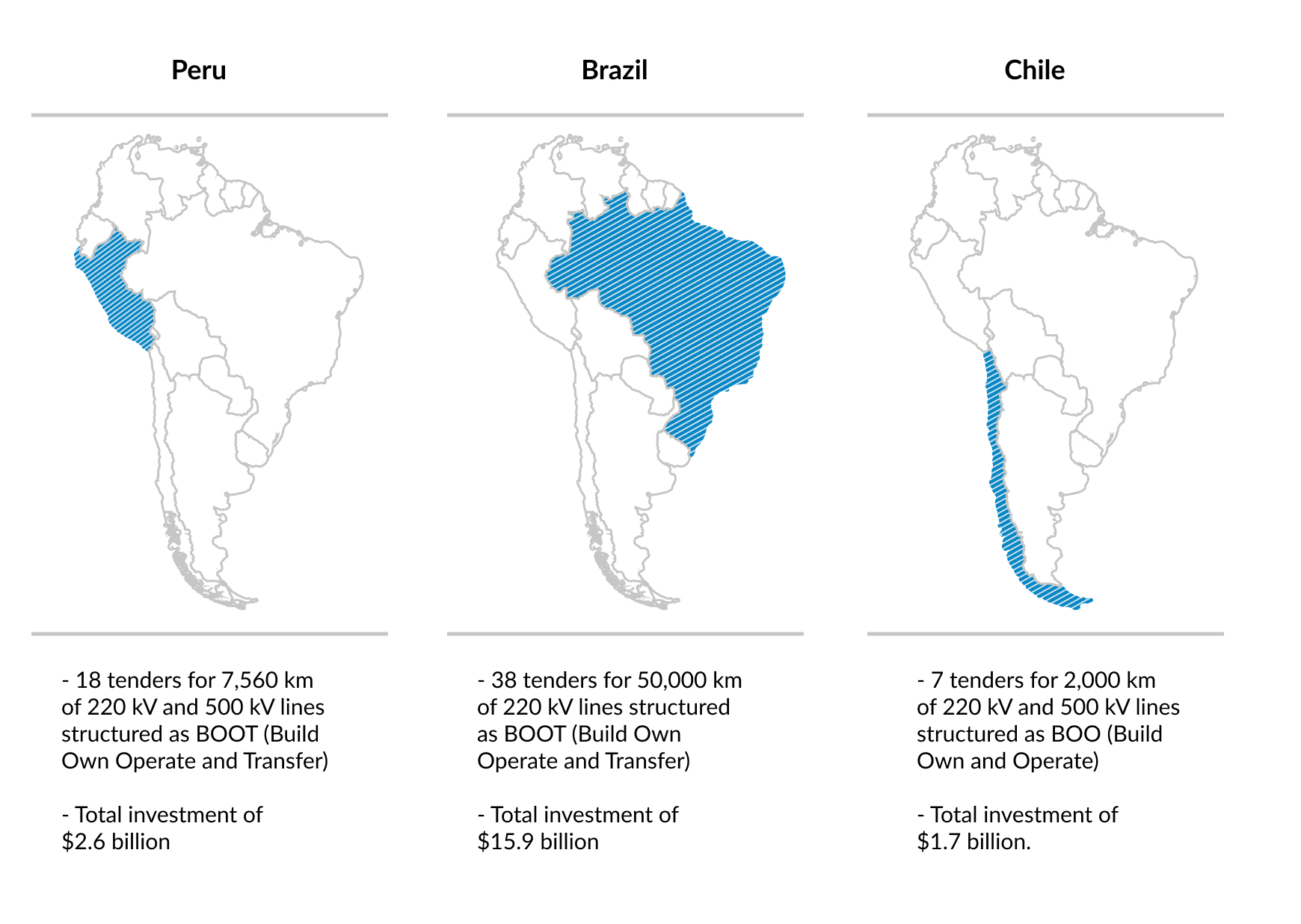

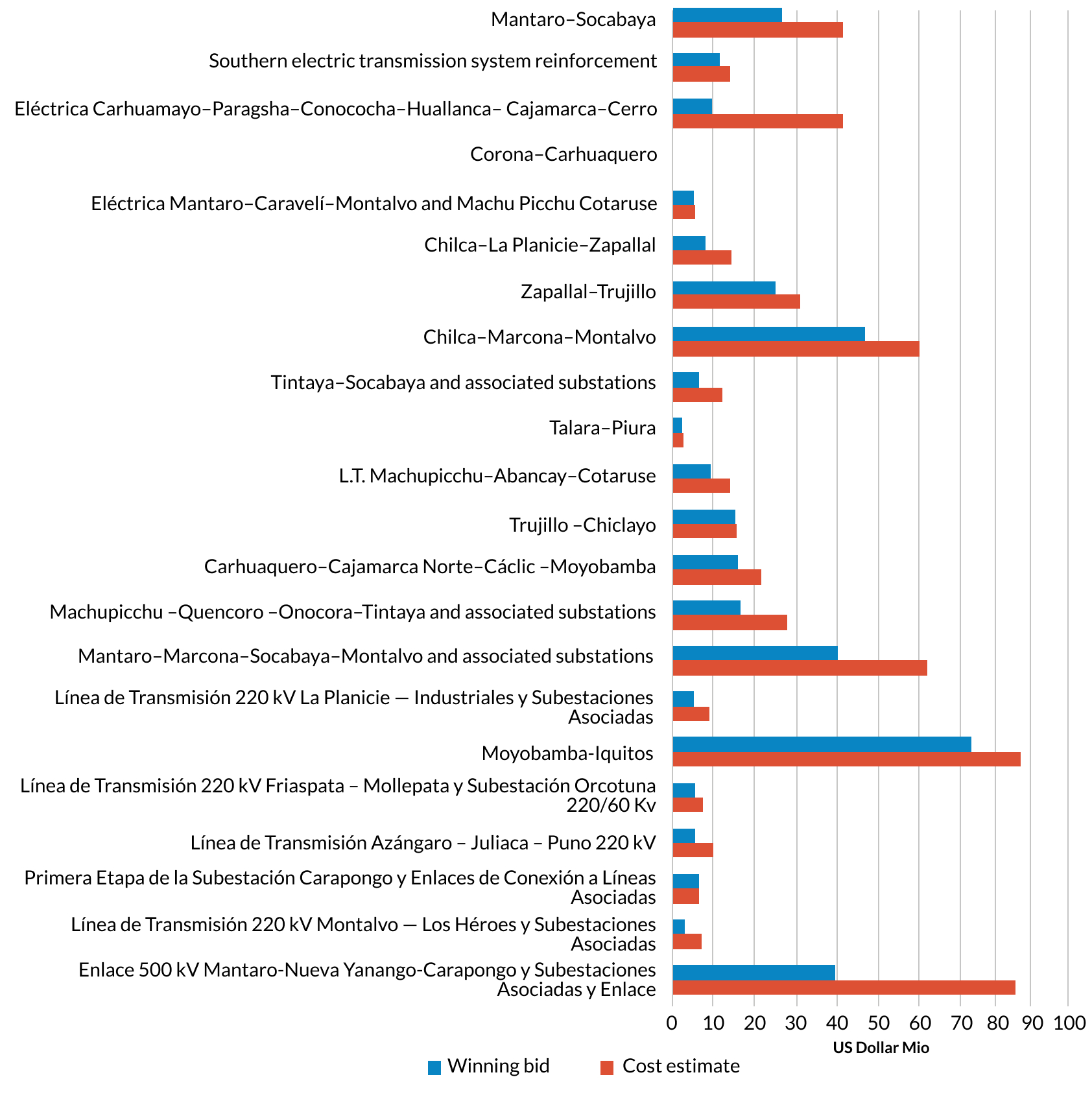

While private investment is not as widespread in transmission as in power generation, there is substantial experience worldwide. In addition to well-functioning power markets in OECD countries (e.g., United Kingdom), private transmission has become common in the last twenty years across Latin America and in countries such as India, Kazakhstan, and the Philippines. Just in the period 2000-2015, multiple projects materialised in Latin America as summarised in Figure 1.2.

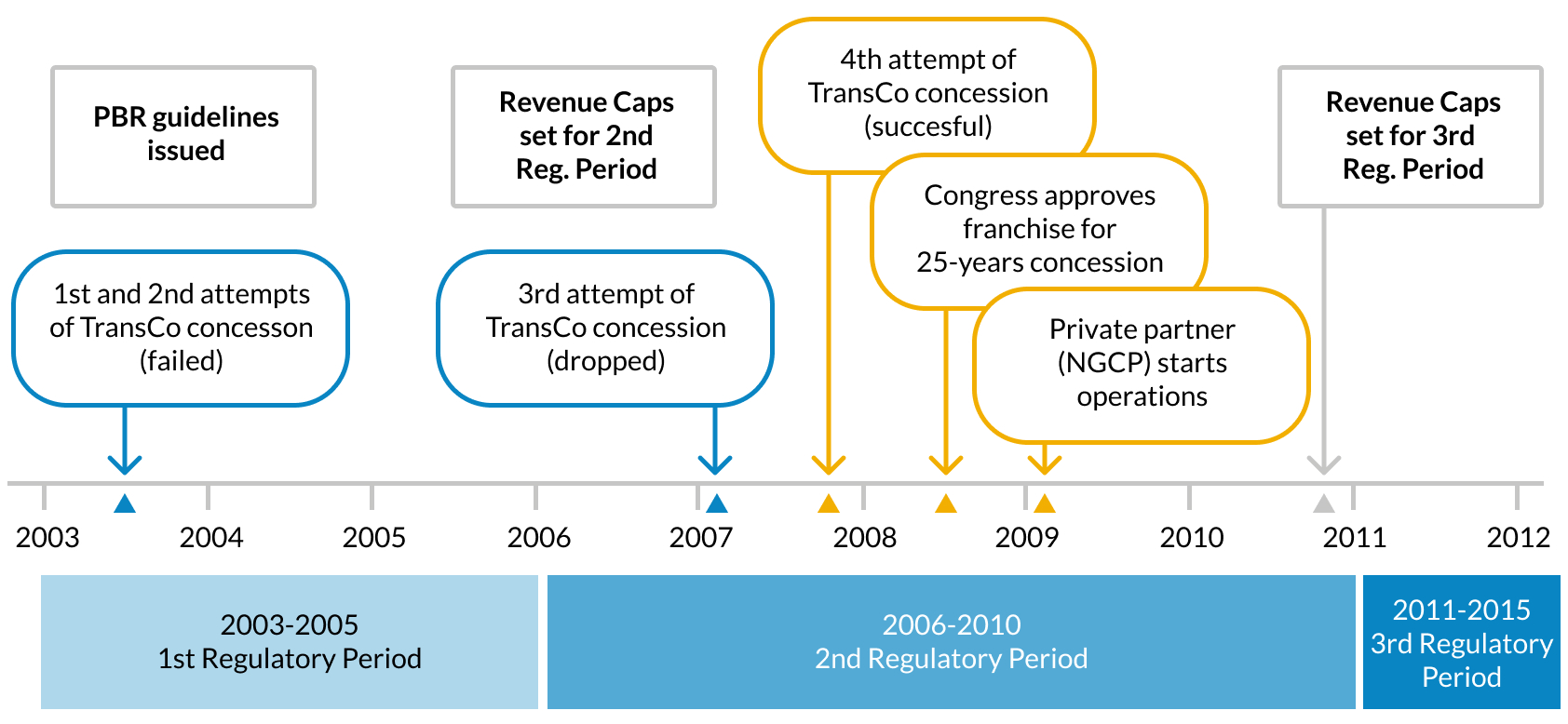

Similarly, India has developed more than 500 km of 400kV and 765kV lines through private investment. Kazakhstan has a privately owned and financed transmission system, and the Philippines privatised their existing transmission system through a 25-year concession in 2009.

Sub-Saharan Africa was able to leverage the experience from other markets to adopt new business models and avoid legacy infrastructure (for example, deploying wireless data/voice systems rather than installing landlines). In the same way, the African energy market can learn from the recent experience in peer markets around the world to move past the traditional focus of publicly financed transmission infrastructure and instead foster a dynamic market place that is driven by private investment.

This handbook would benefit all stakeholders involved in the power sector and more specifically in the development of transmission infrastructure. The book is intentionally designed to benefit all levels of readers:

Beginner: The book provides an overview of the fundamental regulatory structure of transmission markets, the planning and procurement of transmission systems and the core principles of contracting and finance that are required to attract private investment. The intent is that with this essential background information in mind, the detailed explanation of private investment models will be easier to understand.

Utility/Regulator: The observations and guidance in this handbook are presented from the perspective of a public official in an utility or a regulator. Specifically, the assumption is that such an official has already recognised the need to bring private-sector investment into the market. Further, the book assumes that the official is considering the required adjustments to the existing regulatory framework and the specific obligations in any partnership with a private-sector investor to develop transmission infrastructure.

Procuring Agency/Negotiator: Perhaps the greatest value that we can convey in this book is the collective experience of the authors in planning, procuring and negotiating transmission projects. As a result, the book contains significant detail on the structuring of private transmission projects, the allocation of risks and obligations within those structures, and related considerations around financing and regulatory compliance.

In addition to the public sector readers described above, this handbook should also be helpful to other sector participants including the transmission companies, transmission system operators, regulators, investors, and financial institutions as it presents a diverse set of considerations that those parties must address in their role in the development of private transmission projects.

The knowledge and guidance presented in this book are not intended to represent the opinion of any one author. As emphasised throughout this book, the development of transmission infrastructure through a partnership between the public and private sector requires close collaboration between stakeholders and the application of expertise from many disciplines. To hold to this guiding principle, the development of this handbook also brought together a diverse group of stakeholders and experts. Our group of authors, who each contributed their time on a pro-bono basis, includes contributors from governments, development banks, investment funds, project developers, universities and leading international law firms. Equally important is that our group includes engineers, economists, lawyers and regulators who collectively have over 200 years of experience in the energy sector. Our sincere hope is that the collective wisdom and dedication of this group demonstrates how important it is to make progress in addressing the infrastructure gap in Sub-Saharan Africa and that our contribution will make a meaningful impact on that effort.

The unique conditions for the preparation of this handbook are notable

since they differ from the rest of the Understanding series. As with previous books, this handbook was produced using

the

The authors would like to thank our Book Sprint facilitator Barbara Rühling for her ability to adapt the Book Sprint process to a virtual format and for her patient guidance throughout the hours of staring at our confused faces on a computer screen. The authors would also like to thank Henrik van Leeuwen and Lennart Wolfert for turning our rushed scribbles into beautiful and meaningful illustrations. The tireless work of Book Sprints’ remote staff Raewyn Whyte and Christine Davis (proofreaders), and Agathe Baëz (book design), should also be recognised. It is also important to recognise the considerable planning and development that went into the conceptualisation of this handbook before the drafting process. In particular, our deepest appreciation goes to Elizabeth Clinch (International Program Specialist, CLDP) for the original research at the outset of the concept development and for her tireless work to bring our group together in a virtual space. The authors would also like to recognise the following individuals and institutions that helped focus dialogue to build a consensus around the need for a handbook focused on transmission financing: Jennifer Baldwin (Power Africa); Megan Taylor (Power Africa); and Kenyon Weaver (Commercial Law Development Program). The authors would also like to thank the generous funding and logistics support from the United States Agency for International Development’s Power Africa programme and the African Legal Support Facility.

To continue the tradition of open-source knowledge sharing that is at the core of the Understanding series, both as a standalone reference guide and as a jumping-off point for further discussion and scholarship, the book is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY NO SA). In selecting this publication license, the authors welcome anyone to copy, excerpt, rework, translate and/or re-use the text for any non-commercial purpose without seeking permission from the authors, so long as the resulting work is also issued under a Creative Commons License. The handbook is initially published in English with translated editions soon to follow. The handbook is available in electronic format at http://cldp.doc.gov/Understanding as well as in print format. Many of the contributing authors are also committed to working within their institutions to adapt this handbook for use as the basis for training courses and technical assistance initiatives.

This handbook is the fifth in the Understanding series published by Power Africa. The first handbook,

Gas and LNG Options

|

Reason Abajuo Legal Counsel African Legal Support Facility |

Samson O. Masebinu Development Assistance Specialist: Energy Finance USAID/Power Africa (South Africa) |

|

Mohamed Rali Badissy Professor of Law Penn State Dickinson Law (USA) |

Subha Nagarajan Managing Director Global Capital Advisory (USA) |

|

Christopher Flavin Business Development Director Gridworks (UK) |

Gadi Taj Ndahumba African Legal Support Facility |

|

Jay Govender Projects and Energy Sector Head Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr Inc. |

Kaushik Ray Partner Trinity International LLP (UK) |

|

Ryan Ketchum Partner Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP (UK) |

Stratos Tavoulareas Energy Advisor and Visiting Scholar George Washington University (USA) |

|

Julius Kwame Kpekpena Chief Operating Officer Millennium Development Authority (Ghana) |

Omar Vajeth Principal Corporate Relations Officer African Development Bank |

|

Mohammed Loraoui Attorney Advisor (International) U.S. Department of Commerce (USA) |

The business models used to finance transmission infrastructure are heavily impacted by sources of funding for the sector. Before introducing the different business models, it is necessary to understand the various external funding options and their criteria, which this chapter explores.

In the next chapter 3. Common Funding Structures in the African Market, we discuss the status quo of transmission infrastructure financing in the African continent — the public sector structures generally used to finance these types of projects at present. We then look to business models involving the private sector in chapters 4. Introduction to Private Funding Structures, 5. Independent Power Transmission (IPT) Projects, 6. Whole-of-grid concessions, and 7. Other Private Funding Structures.

Transmission projects will go through a detailed planning phase before a source of financing and a business model are selected. Chapter 9. Planning and Project Preparation explains this process.

The risks highlighted in chapter 11. Common Risks must also be considered as these will impact sources of funding as well as business models. The funding decision will have implications for the introduction of the private sector or continued reliance on public sector funding, and together these will inform the business model selected.

Below we set out the broad principles of financing that have been or could be applied to the funding of existing and future transmission infrastructure projects.

Many businesses, especially large businesses in capital intensive industries, raise debt funding on the strength of their balance sheets, the stability of their revenues, and their ability to service their debts. They do not grant security over any part of their assets to lenders or bondholders, and they agree with each lender that they will not grant security over their assets to any other or future lenders. This type of financing — financing that does not involve the grant of security over a company’s assets — is referred to as corporate finance.

When considering corporate finance in the context of funding transmission infrastructure, the relevant entity procuring funding has historically been the national transmission company of the country. The financial health and liquidity of this entity’s balance sheet (assets and cash flows) will determine its borrowing capacity (which can be enhanced with government support). If the credit of the national transmission company does not allow it to raise debt, additional support from the government’s balance sheet will be required to secure external debt.

In a project finance context, the funding is secured against the viability of a specific project. In this option, a project company is created for financing, constructing and potentially operating the transmission assets and is financed with a mix of equity and debt. In typical project finance funding structures, the project company also retains ownership of the transmission asset. A lender considers the revenue generated by the transmission project as the primary, and often singular, source of loan repayment. The projected cash flows after meeting operating expenses must be sufficient to service debt in terms of capital repayment and interest. The cash flows available after debt service should also provide a reasonable return on equity.

The predictability, sufficiency and certainty of cash flows will determine the project company’s borrowing capacity to finance the project. If the project underperforms and the borrower defaults on the loan as a result, the lender will have the right to enforce its security on the project company’s assets. If liquidating the project company’s assets is insufficient to recover the balance of loan owed due to default, the lender will have no recourse to the owner(s) of the project company for further compensation: the sponsor's liability is limited to the investment it has made via its equity contributions. Therefore, the key to project finance is the underlying revenue stream generated by the asset in question (e.g., annuity, use of system or wheeling charges for a transmission infrastructure project).

If the transmission asset is not linked to a dedicated generation facility or a large industrial consumer, and there is uncertainty as to how well-utilised the transmission infrastructure will be, lenders will expect a payment regime similar to a fixed capacity payment or fixed availability payment. Such payments are not vulnerable to changes in the amount of power flows on the transmission line.

In the context of transmission infrastructure, an entity’s borrowing capacity via corporate finance is limited by its existing balance sheet, including how much existing debt it has (and the state of its revenues and assets). Any existing balance sheet constraints will limit the borrowing capacity of transmission utilities to fund transmission infrastructure using corporate finance structures. The state utility may have the opportunity to borrow further with government support. Project finance structures, however, do not look at the transmission company’s borrowing capacity because the debt capital raised is treated as off-balance-sheet financing.

Under corporate finance, since repayment is divorced from a transmission asset’s underlying economic value or performance, repayment risk will be a function of a borrower’s existing level of leverage compared to the financial or market value of its total assets to determine its liquidity. A healthy balance sheet will attract a lower cost of financing (more efficient pricing). As the credit quality of an entity decreases, the cost of funding increases due to higher risk perception.

Under the project finance option, since repayment is secured via project revenue, lenders will focus on mitigating all risks to those cash flows. Project finance transactions tend to be highly structured and complex, with emphasis placed on appropriate contractual allocation of risks that impact the underlying revenue stream. This adds to the time and cost of pulling together the number of stakeholders and related documentation. The pricing of the project is influenced by the perceived risk of the cash flows, the credit quality of the source of those cash flows, and if needed, the enhancement of these cash flows.

Transmission networks require ongoing investment. Ongoing investment requires continuous capital injections in the business in the form of new projects or upgrades of existing assets. As a general rule, state-owned transmission utilities, whole-of-grid concessionaires, or privatised utilities will typically find it more practical to raise debt financing using corporate financing techniques. In contrast, a project company established to implement an independent power transmission (IPT) project will use project finance to allow for higher debt to equity ratios, longer tenor, and limited recourse for the shareholders in the project company. Given these factors, IPTs are likely to be financed using project finance techniques.

The sources of capital for a transmission project will depend upon the outcome of the planning, risks related to the project, and a government’s and state utility’s balance sheets and the ability to raise finance. In chapter 3. Common Funding Structures in the African Market, the existing model of government balance sheet financing for these assets is discussed in more detail, and in later chapters, we discuss some private sector finance models. Below, we set out the typical capital sources — government budgetary allocation, debt, and equity — and indicative terms used in most funding models.

In the context of its annual budget, a government may choose to allocate a certain amount of the fiscal budget to the development of the country’s transmission infrastructure. When an allocation is made, the specific method of application of these funds is likely to vary from one government to another depending on the country’s laws and conventions for public procurement of infrastructure. In some jurisdictions, the funds will be managed and applied directly by the Ministry of Energy (or equivalent); in others, they may be channelled via a department of public works or the state-owned entity licensed to construct and maintain transmission infrastructure. Nonetheless, the source of these funds will invariably come directly from the government’s accounts or “balance sheet” as shown below, and thus the government’s ability to finance transmission infrastructure through a budgetary allocation will depend on the country’s priorities and fiscal constraints. Ultimately, the decision as to whether to use this model will depend on the government’s balance sheet (i.e. availability of cash) and its expenditure priorities (based on its current policies) given a country’s wider infrastructure investment needs.

In practice, financing transmission infrastructure through budgetary allocations is difficult and has become increasingly rare. The size of the investment puts significant pressure on a government’s budget and its available cash. The allocation can be structured in a way as to accumulate yearly until reaching the required amount, but depending on the size of the investment, the desired amount may take many years to be collected. Furthermore, in addition to slowing down the development of the power grid, this approach requires significant fiscal discipline as the government needs to set aside the funds each year and resist the temptation to use them when a crisis or economic downturn arises.

Transmission infrastructure necessitates long-term funding, given the relatively high capital expenditure required for identification, development and construction. Given constraints in local commercial banking markets, public financial institutions are an important source of debt financing for transmission infrastructure.

The stakeholders and financial products described below cover both public and private sector debt financings — their application in real-world scenarios is dealt with in later chapters.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and donor-backed funds can lend directly to governments on concessional or grant terms for identified projects which follow the MDB procurement guidelines, and can also be lenders for the financing of independent power transmission projects in the private sector.

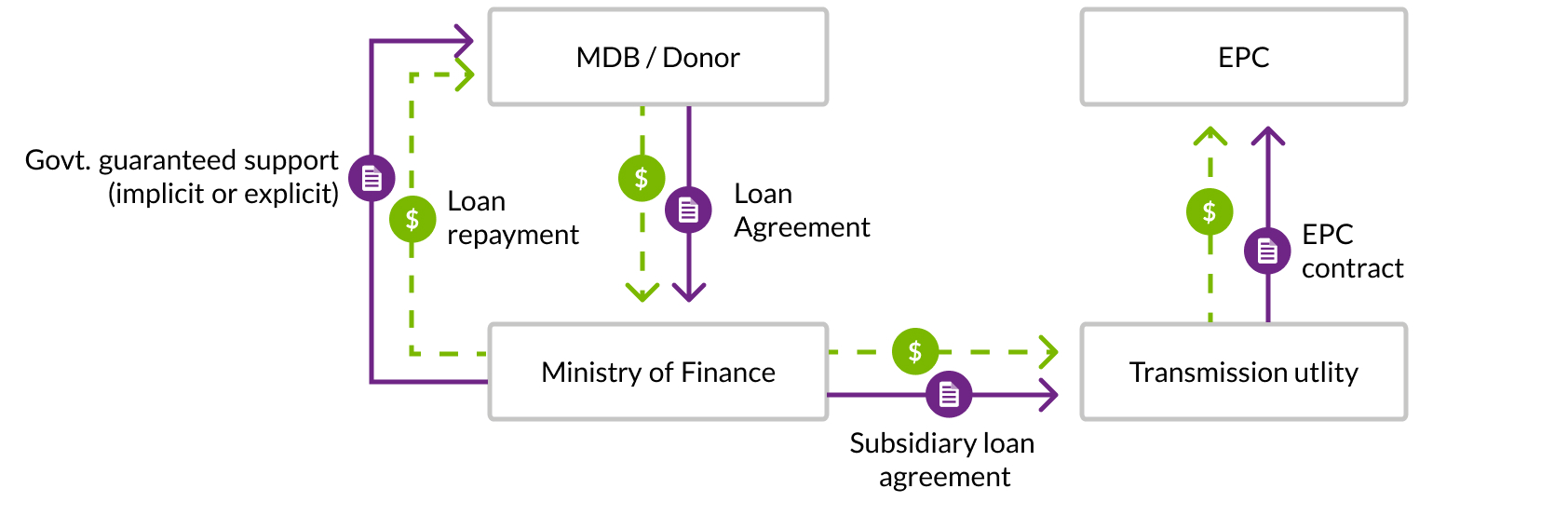

Examples of MDBs, which provide concessional finance, include the African Development Bank, European Investment Bank, and the World Bank Group. Concessional in this context means that the terms of the loan are likely to include low or subsidised interest rates, extended grace periods, and long amortisation schedules that can extend beyond 30 years. Typically these loans are provided to the government via the Ministry of Finance, and on-lent to the transmission utility. These loans are accounted for on the government’s balance sheet, typically as both an asset and a liability. The transmission company will own the asset, but repayment, if required, will be secured from the government's balance sheet. MDB and donor concessional money may be used to settle contractor invoices directly, but the government remains the obligor.

Transmission projects funded through MDB concessional funds can in some instances take longer to secure the funding and the necessary contractors. This is often the case where the government or the utility does not have the necessary capacity to manage the high degree of coordination, planning, and adherence to MDB procurement guidelines for such projects. In addition, MDBs have country and sector limits (often called “funding envelopes”) that are available to countries for this type of financing support which get revised based on the country’s capacity for debt and the requirements of the ministries. When the funding envelopes may be nearing their limits, countries will have to prioritise the infrastructure projects they want to support. Bilateral donor agencies can be another source of grant or heavily subsidised financing which can provide sector viability gap funding or support to an individual transaction.

Private sector MDB funding

The same MDBs have “private sector windows”, i.e., funding available for private sector projects, such as IPTs. These are loans granted on commercial terms rather than concessional terms, and for tenors up to 18-20 years. Importantly, private sector MDB loans are not captured on the government’s balance sheet, unless a government guarantee or financial backstop helps secure repayment. The structures under which MDBs participate in IPTs are set out further in chapter 5. Independent Power Transmission (IPT) Projects.

Export Credit Agencies (ECA) are institutions that are publicly owned financing agencies that help finance national exports by providing direct loans, guarantees, or insurance to overseas buyers, including entities such as transmission companies. ECA finance can be used in the public sector, in government balance sheet financing, and project finance involving IPT structures.

Examples of active ECAs in Sub-Saharan Africa include the Export Credit Insurance Corporation of South Africa, US Export-Import Bank, UK Export Finance, BPIfrance, SERV from Switzerland, Euler Hermes from Germany, and the Export-Import Bank of China. Some of these agencies can provide local currency solutions in certain jurisdictions, but for the most part, provide USD and Euro denominated loans.

To ensure financing discipline and promotion of fair and transparent trade practices, financial terms and conditions follow guidelines set by the OECD, called the OECD Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits guidelines. Eligible financing is typically up to 85% of the relevant export contract, with some allowances to cover a portion of local on-shore costs, but the expectation is that the government (or borrower) covers the 15% balance, usually in the form of a down payment in cash. Financing terms include longer tenors than commercial banks can competitively price or sometimes provide to borrowers in certain jurisdictions (up to 12 years for corporate finance and 14 years for project finance loans), but the cost of funds is generally more expensive than concessional borrowing. For transmission infrastructure associated with a renewable energy generation project, the OECD Arrangement allows project finance loans up to 18 years, on an exceptional basis.

In the context of transmission infrastructure, ECAs can provide (1) corporate finance loans, underwriting the sovereign’s capacity to repay the loan, lending directly to Ministries of Finance, which helps to reduce the cost of financing, and (2) project or corporate finance loans to IPT special purpose vehicles (SPVs) or private companies, respectively.

Depending on the ECA, they can either lend directly or insure/guarantee (between 95-100%) a commercial bank that will provide funding, which will be reflected in the commercial bank’s lower cost of funds to the project.

Development Financial Institutions (DFIs) which include MDBs, are usually majority-owned by national governments and source their capital from national or international development funds, or benefit from government guarantees. This ensures their creditworthiness, which enables them to raise large amounts of capital from international capital markets and provide financing on very competitive terms. DFIs can provide up to 15 to 20 years, long tenor competitive commercial lending to projects with some degree of private ownership. Some examples of DFIs active in Sub-Saharan Africa include the Development Bank of South Africa, Development Finance Corporation from the US, the CDC group from the UK, Proparco from France, and FMO from the Netherlands.

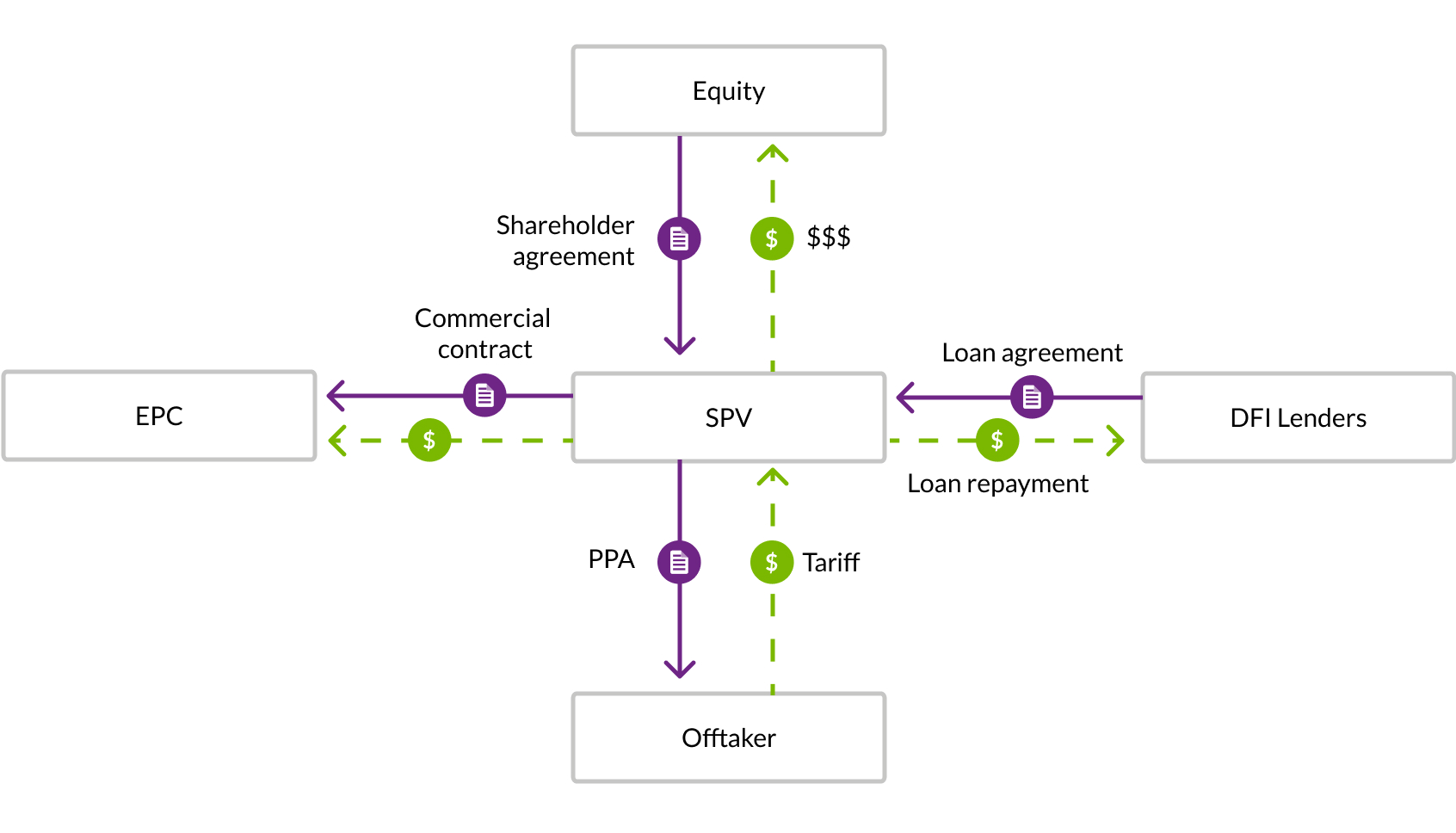

Some DFIs can provide loans to state-owned utilities which demonstrate independent governance, depending on that utility’s balance sheet and ownership of assets. All DFIs can provide commercial project finance debt to a project company, which can be used in IPT transactions. The diagram below shows a DFI-funded project finance structure.

In addition to lending, some DFIs such as the AfDB and the WBG can

offer a guarantee and insurance products to help credit enhance a

project structure by covering off certain credit or political risks.

Guarantees include partial credit guarantees (PCGs) and partial risk guarantees (PRGs) to cover commercial lenders and investors against the risk of a

possible government failure to meet contractual obligations to a

project. Please see the

Some DFIs provide political risk insurance (PRI) to mitigate and manage risks arising from the adverse action, or inactions, of governments that go against contractual obligations. PRI can also be used to backstop termination support under a government guarantee or other forms of government undertakings if the government is unable to pay as per its contractual obligation.

Green/climate-backed financing

There are many clean technologies and climate change donor-backed funds which can provide grant funding to support grid modernisation and transmission lines, if the infrastructure can be linked to projects and initiatives which promote and advance sustainable development and encourage the development of a more sustainable economy, for example, renewable energy generation. Given the emphasis that many countries are placing on decarbonisation to support countries on their journey to a green energy transition, it is expected that the EU and other publicly backed institutions will make more grants or highly concessional finance available to support these activities.

The advantage of these resources is that they provide subsidised financing, which, when combined with more commercial sources of funds, can help blend the cost of capital to reduce financing costs for transmission infrastructure.

Transmission is the enabling infrastructure for renewables, and, as such, it should be credited with greenhouse gas reductions and be eligible for green financing. In addition, the strength of the existing transmission and grid networks will determine how much greenfield renewable energy generation a country can support. Many emerging countries with mandates to significantly scale up renewable energy generation will need to simultaneously invest in upgrading and expanding their transmission network to support greater renewable energy penetration. While this is still an evolving field, greenhouse gas reduction calculation methodologies have been considered by numerous organisations and both governments and developers should monitor progress to identify potentially attractive financing options.

In addition to DFIs, commercial banks provide debt financing to transmission infrastructure projects. Commercial banks are privately owned banks that participate and provide funding to a range of projects, including transmission projects. Commercial banks more typically lend to projects that have creditworthy cash flows or cash flows that are enhanced with cover via DFIs or ECAs.

Typically, commercial banks are financial institutions that are regulated by central banks and other international banking regulations which impact the level of liquidity, risk thresholds and pricing.

Blended finance

Providing hybrid private sector/donor funding for IPTs, for example, can significantly boost the availability of funding to the sector. The provision of grant funding for a project is unlikely to impact returns for investors positively or negatively since funding models for this asset class are typically fixed or capped. The impact of such funding would be to increase the number of projects which can be undertaken.

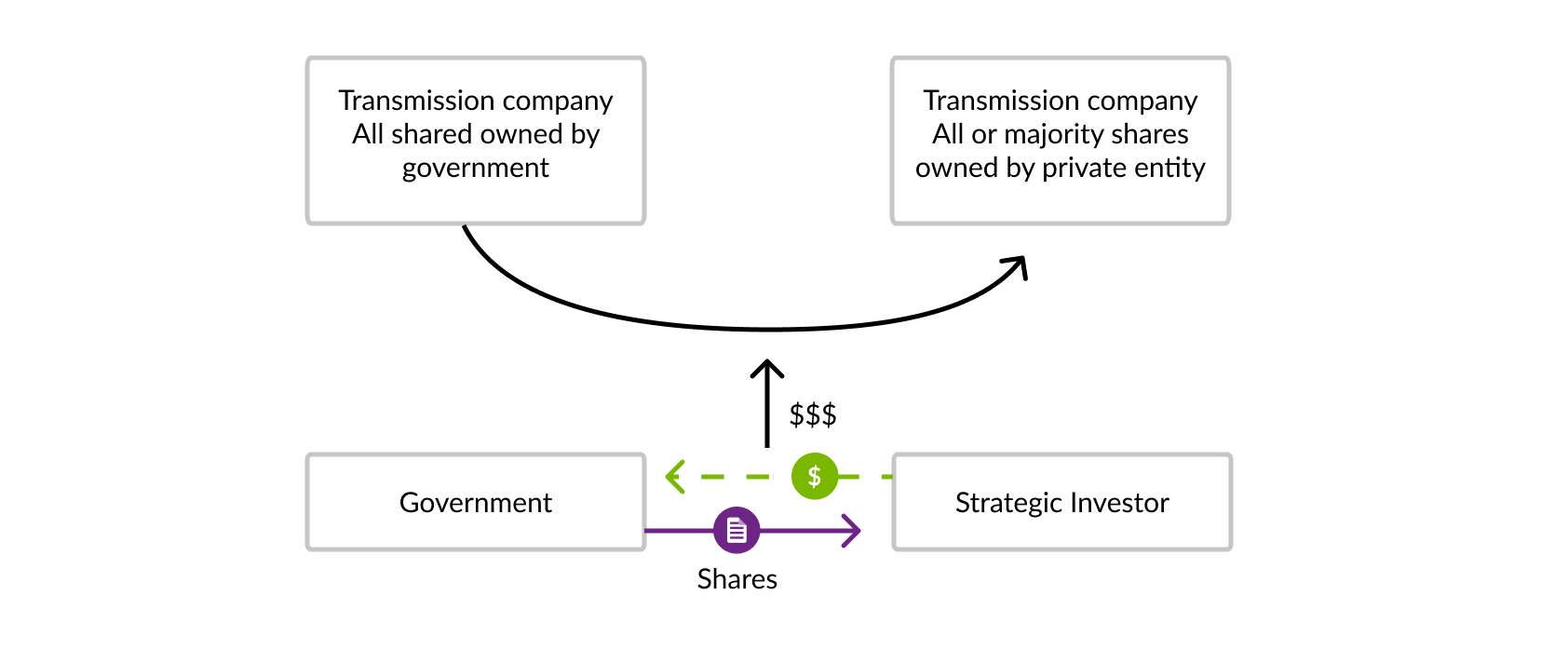

In IPT and other project finance structures, lenders generally require project owners to invest an amount of equity in exchange for shares in the project company, usually for at least 20-30% of the total project cost. This form of long-term capital earns dividends over the life of the project which are paid from the remainder of cash flows after operating expenses and debt service obligations have been met. The capital structure and cash waterfall are intentionally aligned so that equity owners are incentivised to ensure that the transmission assets are constructed and perform as contractually specified, to generate and collect the forecasted revenue. Equity providers for transmission infrastructure include:

In some instances, state-owned transmission companies or energy utilities also invest capital (or some other form of consideration) into a project company and acquire equity interest.

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce some private sector business models which have been applied to finance transmission infrastructure in other parts of the world. More detailed information on the different funding structures will be provided in the following chapters which dive into the details of each model. This chapter aims to provide tools to ensure that well-informed decisions can be made. More specifically, we will look at key considerations in determining whether these business models are, or could be, applicable in a particular country or market.

Which model is more suitable for a country or a specific project depends on many factors which are country and project-specific. A detailed assessment is recommended to identify all the relevant considerations and provide the advantages and disadvantages of the various options, so the government can make the best decision. Nevertheless, whilst private sector involvement in the transmission sector can take many forms, this book will discuss:

The two most applicable structures to the African context based on the current state of its electricity supply industry are the IPT and the whole-of-grid concession. For this reason, more details will be provided on these two models than on privatisation, merchant lines, and industrial demand-driven models.

An obstacle to privately financed transmission infrastructure is often the perception that the national power company or transmission system operator (TSO) will lose control over the sector. On the contrary, in many cases, the private investor builds the transmission project and turns over the operation of the assets to the TSO immediately upon completion of construction and project acceptance. In other cases, the private investor only owns and operates physical transmission assets without managing the electrical system and coordinating generation dispatch and power flows.

Another important consideration is that ownership and control do not have to be held under the same organisation. Who owns the transmission infrastructure may vary depending on whether it is an IPT or a whole-of-grid concession. It is also possible to find variations within the same model. For example, an IPT may be entitled to own the infrastructure which it constructs on a long-term basis, but it may also be a condition of the project documents or a condition of the relevant licensing regime that ownership of the assets is transferred to the state-owned utility or another state-owned entity at the end of a fixed period.

Furthermore, operation and maintenance can be separate as maintenance of the transmission assets (under the project) can be carried out by the private investor or a maintenance contractor or even be subcontracted to the national transmission company.

Depending on the objectives of the government, it is, therefore, possible to calibrate the degree of control retained in respect of the transmission asset as well as define the ownership of the asset during and after the duration of the core agreement.

Although there are many advantages to private funding, the nature of the financing will also carry constraints and requirements. When choosing a private funding model for financing transmission infrastructure, a government must be aware that it will require efforts in negotiating a complex commercial transaction often driven by well-established market standards. This is especially true when it comes to project finance which is typically the method of financing for IPTs.

Risk allocation is the key component of project financing and by extension may determine the success or failure of the privately-funded transmission project. While there is a natural tendency to attempt to shift risks to other parties, it is wise to keep in mind the golden rule of risk management: Each risk should be allocated to the party that is in the best position to first control/reduce it and then manage it. Imposing risks on the private investor, even though it is not in the best position to manage them, will typically result in a more expensive or even unbankable project. Allocating the risks to the party which is in the best position to manage them will help to de-risk and reduce the overall cost of the project and the final tariffs.

There may be concerns that the legal/regulatory framework may not be ready for some forms of private investments. Although this may be a genuine challenge, it is not an insurmountable obstacle. It is usually possible to put some of these models in place within existing frameworks. If legal change is required, the project could be structured to address the lack of laws/regulations (regulation by contract) and can be used as a testing ground to learn from and ensure that the laws/regulations which are finally approved are the right ones for the country.

As is the case with all power projects, transmission projects have many risks, some unique to transmission and others similar to all power projects. The most challenging risks in private transmission projects are: 1) land acquisition (“rights-of-way”) and 2) securing the revenue stream.

While each country and project have their own uniqueness which needs to be taken into account, some important lessons learned have emerged from the numerous transmission projects that have been implemented so far:

We would further note that countries that have successfully delivered IPPs may well choose to replicate some parts of the documentation structure of IPP models into the transmission sector. This may inform, for example, how the risk allocation between the government and the private sector is documented. In countries where political risks are taken by the government by way of a put/call options agreement (PCOA) for example, this documentation method may be replicated in the transmission sector. In other countries, political risks are dealt with in an “implementation agreement” or “concession agreement” and government officials may be more comfortable with both the nomenclature and risk allocation set out in these documents, as negotiated in the IPP space.

While it is important to be efficient and not “reinvent the wheel”, it is also crucial to take a fresh look at how risks are allocated as there may be particular differences in the risk allocation agreed in that country on the generation side that does not apply to the transmission side, due to the specific nature of a particular project.

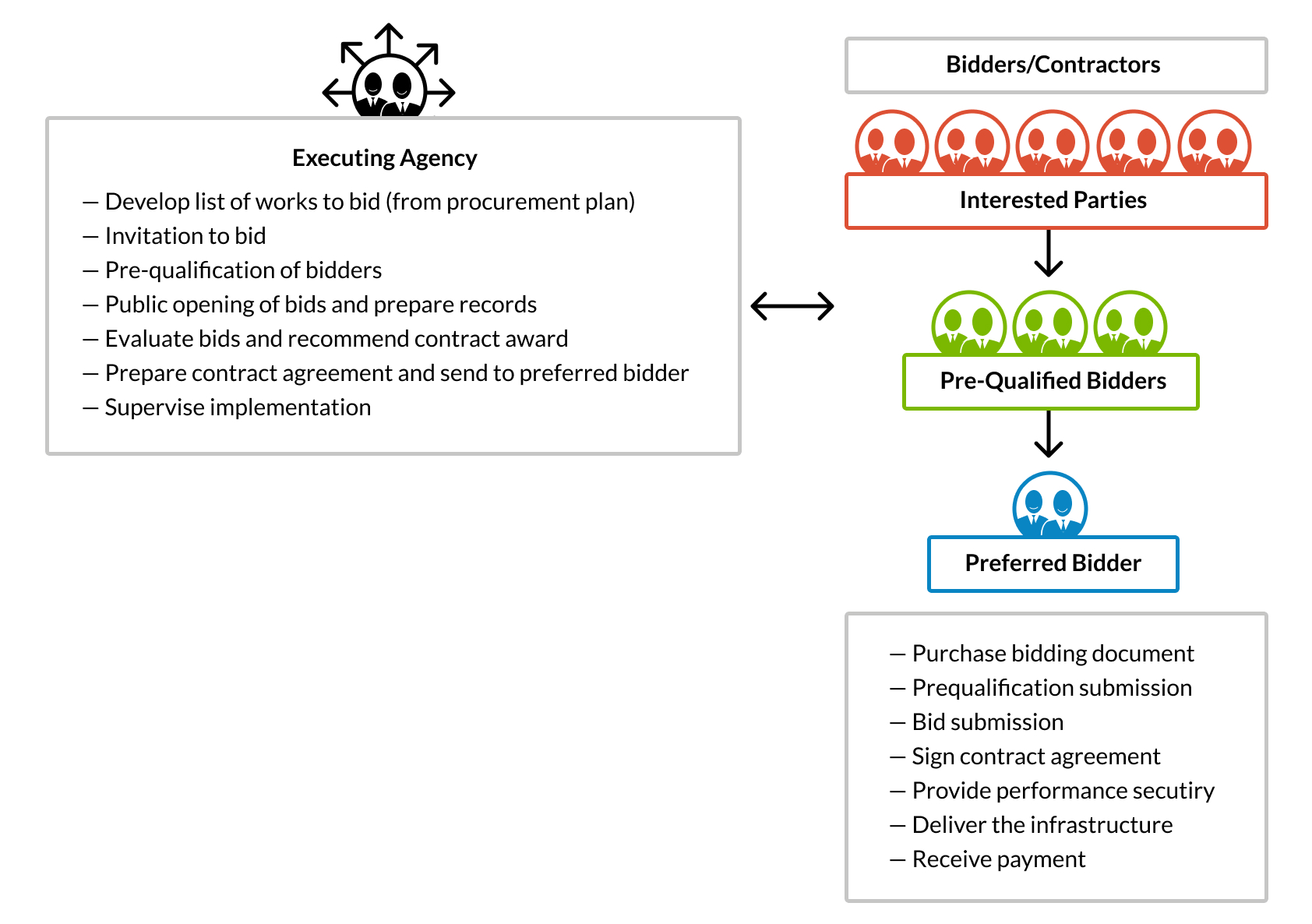

The private developer/investor can be responsible for some or all of the project preparation, design, financing, construction and operation of the project. Depending on how and when the project developer will come on board, it may have substantial project preparation activities to complete. This depends on the procurement approach to select the developer/investor (competitive bidding or sole source).

Financing will typically be provided by other organisations too, including equity and debt. The financial institutions will carry out due diligence of the project including review of the various contracts, as well as assessment of the risks and project “bankability”, ahead of financial closure. At financial closure, the lenders will commit to the project and their funds will be drawn down to fund construction.

The government may have a substantial role to play in the transaction, especially if the project is not commercially viable. The risk allocation matrix in fact should determine the role of each project stakeholder including the government. In an IPT, the investor and the government may enter into a Government Services Agreement (GSA) which supplements the agreement between the investor and the offtaker.

Often, the Multilateral Development Banks have a substantial role to play. In the case of a financially unsustainable power sector, the government might work closely with the MDB to develop a roadmap to power sector sustainability. This roadmap could be developed in parallel with the project but it should include specific milestones which should be monitored and may be linked to the project agreements. Also, the MDBs may provide:

Last but not least, bilateral organisations and donor agencies could play a catalytic role too. They may help with technical assistance in project planning activities, but also they may provide grants or concessional lending because the projects fulfil an important role in the country’s economy. Also, they may provide funding to close the viability gap (e.g., similar to KfW’s GETFiT programme). In this way, scarce grant funding can be used in a targeted way to unlock larger sums of private sector investment. Private sector procurement and management practices can also benefit projects which may otherwise have been solely donor-led or implemented by transmission utilities with capacity shortages or governance shortfalls.

Providing hybrid private sector/donor funding for IPTs, for example, can significantly boost the availability of funding to the sector. The provision of grant funding for a project may not have a positive or negative impact on investor returns since funding models for this asset class are typically fixed or capped. The impact of viability gap funding like this would simply increase the envelope available to multiply the number of projects which can be undertaken.

The purpose of this chapter is to set out, in a non-exhaustive fashion, some of the common methods of funding transmission infrastructure that are currently used on the African continent and to highlight some of their features.

Most of these funding methods are public-sector led. However, they are akin to corporate finance structures as the financing is based on the strength of the government or state-owned utility balance sheets and not on the viability of the cash flows from the transmission projects specifically. These methods include government borrowing/ECA financing and state-owned utility borrowing. Of these methods, government borrowing and ECA solutions (which also require a government guarantee) are by far the most common funding structures utilised.

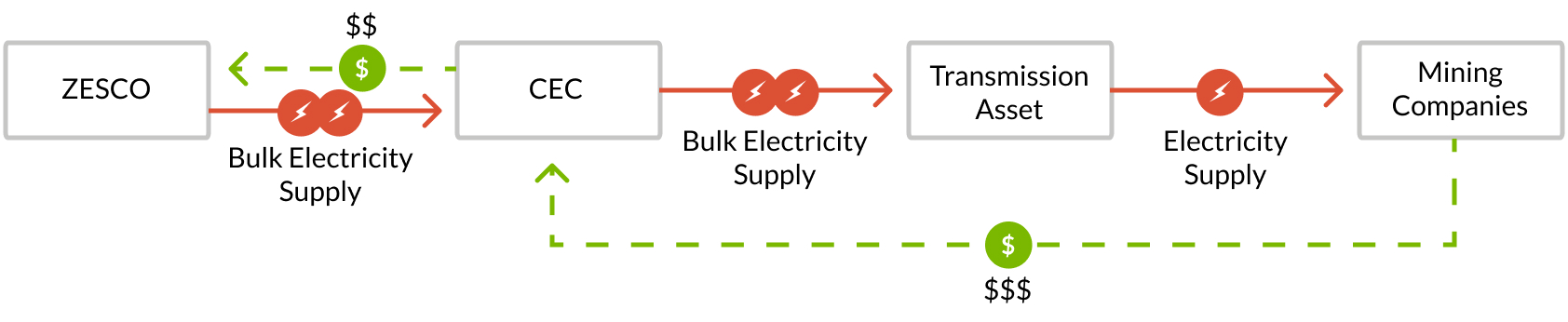

The most common private sector-led funding method used for transmission projects on the continent is the wrapping up of the financing of the transmission project into a related IPP project. This method, discussed in this chapter as the generation-linked transmission model, is the closest to project financing for transmission projects on the continent. As will be discussed in detail in this chapter, the cost of the transmission project is included as part of the construction costs of the IPP project. Since the IPP project is funded using a project financing structure, the costs of the transmission project are typically recouped from the cash flows of the IPP project.

From one country to another, the names of ministries are likely to vary and their functions can be separated differently among fewer or more ministries (e.g., the functions of the Ministry of Finance in one country may be shared between the Ministry of Economic Planning and the Ministry of Finance in some other countries). For this chapter, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) refers to the ministry (or ministries) responsible for raising and collecting both foreign and domestic revenues, managing the budget process and cash resources, setting fiscal policies and forecasting government revenues. The MoF is also responsible for borrowing on behalf of the government and managing the purse strings, which sometimes requires limiting the spending by which ministries try to deliver on their respective policy goals.

In a funding structure using government borrowing, the MoF effectively serves as the borrower on behalf of the government. The borrowed funds will be used for the procurement of the transmission infrastructure and the government accounts will reflect a new debt. Once the funds are borrowed, the government can choose to either procure the transmission line itself or, in turn, lend the borrowed funds to the transmission utility which will procure the transmission infrastructure and repay the government from its revenue (diagram below). Even for the latter scenario, the government remains responsible for the entirety of the debt and will have to pay its lenders even if the transmission utility fails to repay the government.

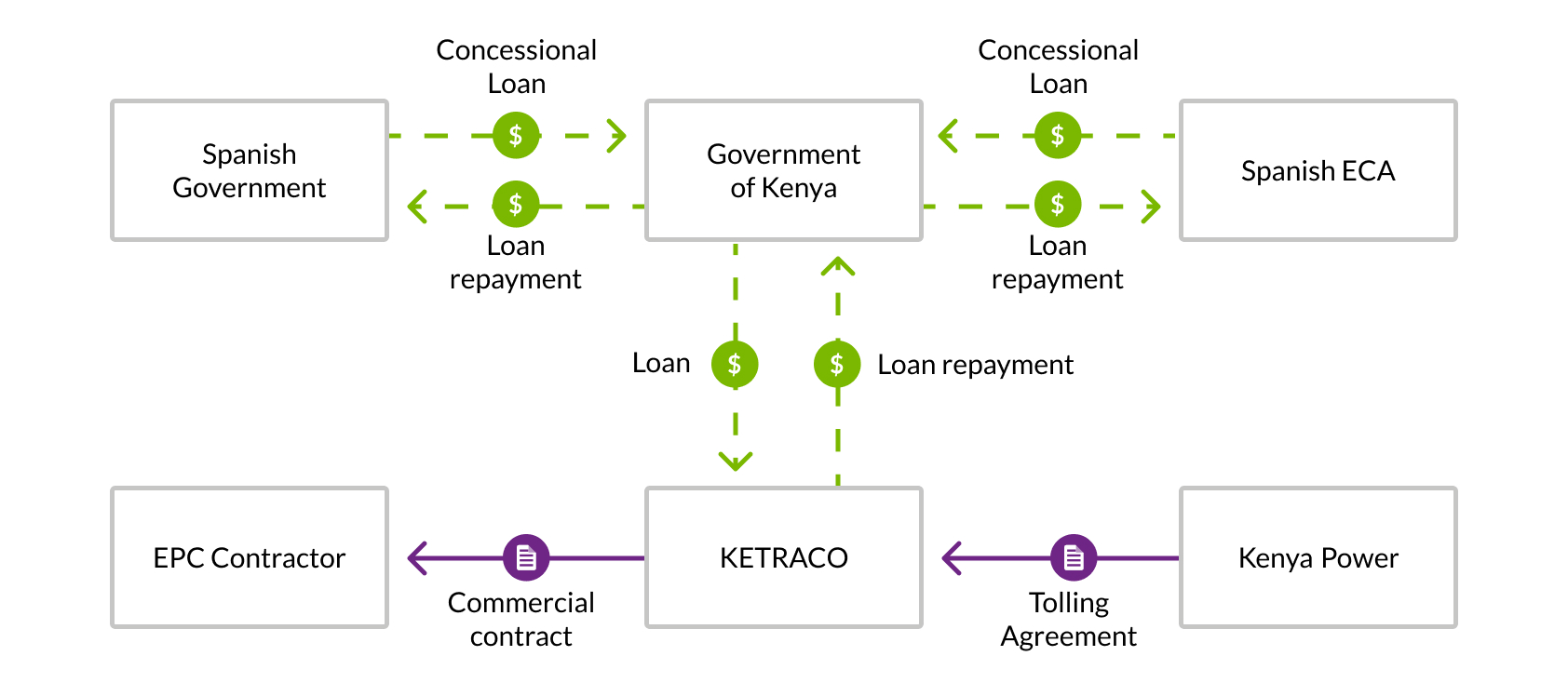

On the African continent, the government is most likely to access financing for transmission infrastructure via concessional borrowing or ECA financing. The borrowed funds are used to procure and pay an EPC contractor to construct the specified transmission infrastructure. As explained in the funding chapter 2. Financing Structures and Capital Sources, MDBs and ECAs can lend to a government via the Ministry of Finance to fund capital expenditure costs. The Lake Turkana Transmission Line case study described below illustrates the use of concessional borrowing and ECA financing for the construction of a transmission line.

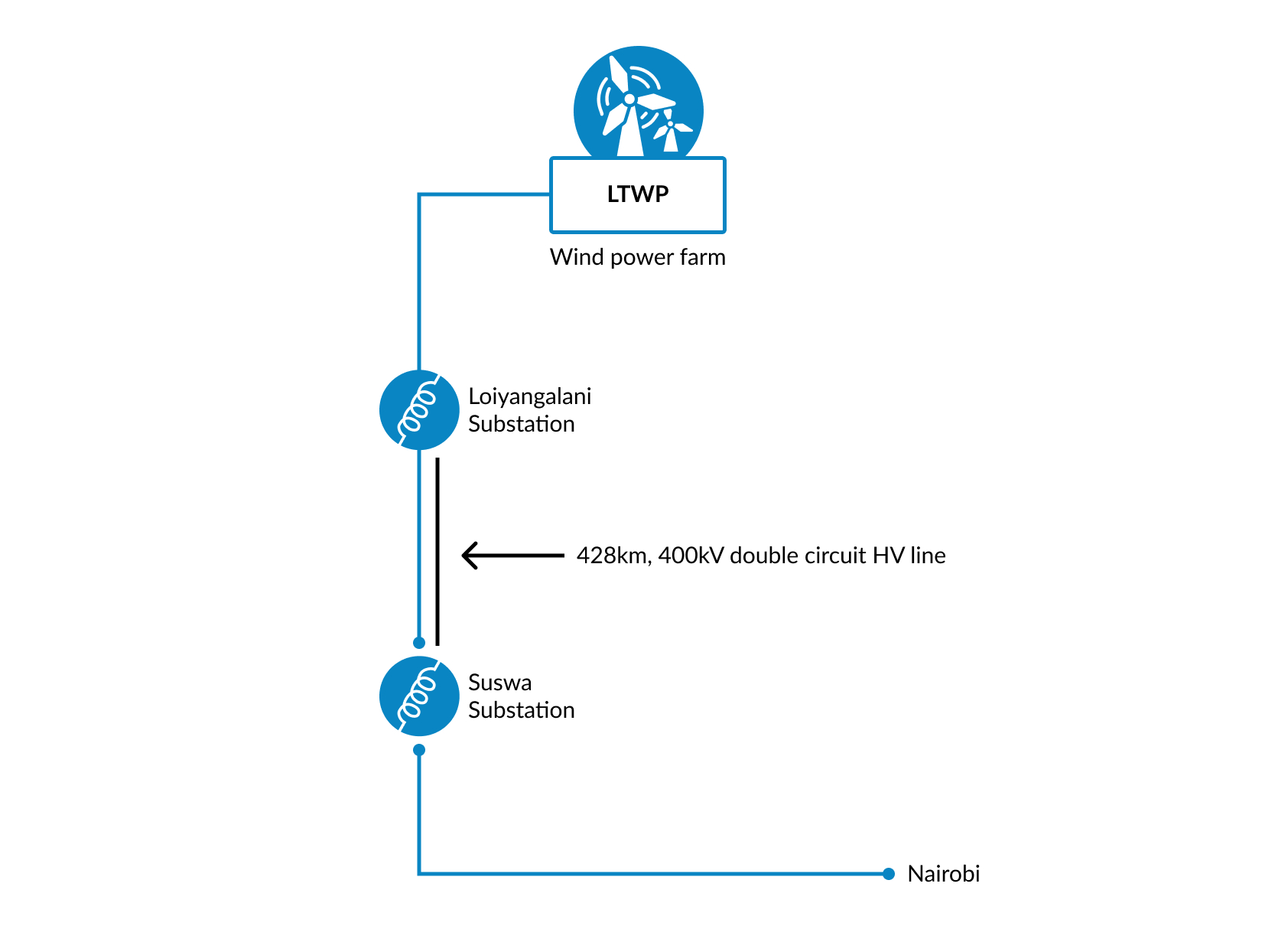

Case Study — The Loiyangalani–Suswa High Voltage Power Line (“Lake Turkana Transmission Line”)

The Lake Turkana Transmission Line starts at the 310 MW Lake Turkana Wind Power plant in Marsabit County, Kenya, and runs south for approximately 428 km to the KETRACO substation in Suswa, Narok county, approximately 100 km west of Nairobi. In 2010, the Spanish government offered to finance the construction of the double circuit line. This included a concessional loan (for 30 years, with a low interest rate) of €55m and a commercial credit in an equal amount offered by the Spanish ECA (with commercial lending sitting behind it).

The Kenya Electricity Transmission Company (KETRACO), created in 2008, agreed to partly fund the line and substation by way of a tolling agreement with Kenya Power. With a large dedicated generation project attached, the potential for future generation projects alongside the transmission line corridor (an area with geothermal power potential) and the possibility for the line to interconnect with the Kenya-Ethiopia interconnector, the economic case for the project was clear.

Interface risk and cost overrun

The initial Spanish EPC contractor who was awarded the contract to construct the transmission line faced many implementation challenges, including a protracted wayleave and land acquisition process for which KETRACO was responsible, which delayed construction works. The initial Spanish EPC contractor subsequently filed for bankruptcy. The transmission line was eventually completed by a consortium of Chinese firms and officially commissioned in July 2019, behind schedule with a $96M cost over run ultimately financed from the government's balance sheet. The Lake Turkana Power Plant had already been commissioned in September 2018, earning deemed energy payments while waiting for the power plant’s connection to the grid to deliver energy to the wider Kenyan grid via the newly constructed line.

Given the Lake Turkana Wind Power project was an IPP and fully developed by the private sector, it raised an interesting discussion of “project on project” risk, with the two projects entirely interdependent but financed by separate means, and the former through commercial sources with the latter via sovereign borrowing. The risk allocation between the various stakeholders was heavily negotiated, with the Government of Kenya (GoK) bearing the responsibility for the timely delivery of the transmission line. The AfDB provided a €20 million PRG to backstop GoK’s completion risk on the transmission line, providing comfort to the Lake Turkana Wind Power lenders that deemed energy payment obligations would be met in the event the transmission line commissioning was delayed.

The Lake Turkana cost overruns highlight the magnitude of the interface risk for interdependent projects. For this reason, transmission lines are often wrapped in the financing and scope of a generation project. Further in this chapter, we discuss generation-linked transmission projects for which it was decided to finance and construct the transmission asset via the same project to significantly reduce the interface risk.

The financing of transmission infrastructure from government borrowing is an attractive method of funding as it can produce favourable terms (e.g., low-interest rate, long repayment period, etc.) provided the government can afford the debt. This type of loan is not extended based on the transmission utility's ability to secure the necessary income to repay the loan but on the government’s fiscal ability to collect sufficient revenue to service and repay the debt. It, therefore, provides more flexibility and allows the government to rely on its full fiscal revenue for the development of the power sector.

Nonetheless, this method of funding requires careful management of the impact of the borrowing on the country’s debt sustainability efforts. Hence, the transmission project will have to compete with other projects as it will ultimately affect the country’s ability to borrow for other sectors of its economy. Moreover, the government will have to ensure that the transmission infrastructure will ultimately improve the viability of the sector as a series of uneconomical transmission financing can easily drain the government’s finances and have long-lasting repercussions on the overall economy. Furthermore, government balance sheet funding may be restricted by other international geopolitical factors as most government borrowing in SSA is provided by other governments, government agencies and MDBs.

Countries with energy sectors that can independently recover their investment and operating costs have state-owned utilities that require minimal government subsidies or interventions to stay financially solvent. There are only a handful of state-owned power utilities in SSA that are sufficiently creditworthy to allow them to borrow from external sources. The repayment of the loan is not necessarily linked to the performance of the underlying asset that has been constructed but secured against other sources of income or revenue generated by the state-owned utility. The state-owned utility borrowing can be from ECAs and DFIs or the capital market.

An ECA and some DFIs can lend directly to the state-owned utility to fund the capital expenditure (CAPEX) requirements of a specified transmission infrastructure project, securing repayment against the utility’s balance sheet. Whereas the DFI will be agnostic on sourcing, as described above, the ECA will finance and disburse against invoices for a specified EPC scope of work which shows equipment and services from the ECA country.

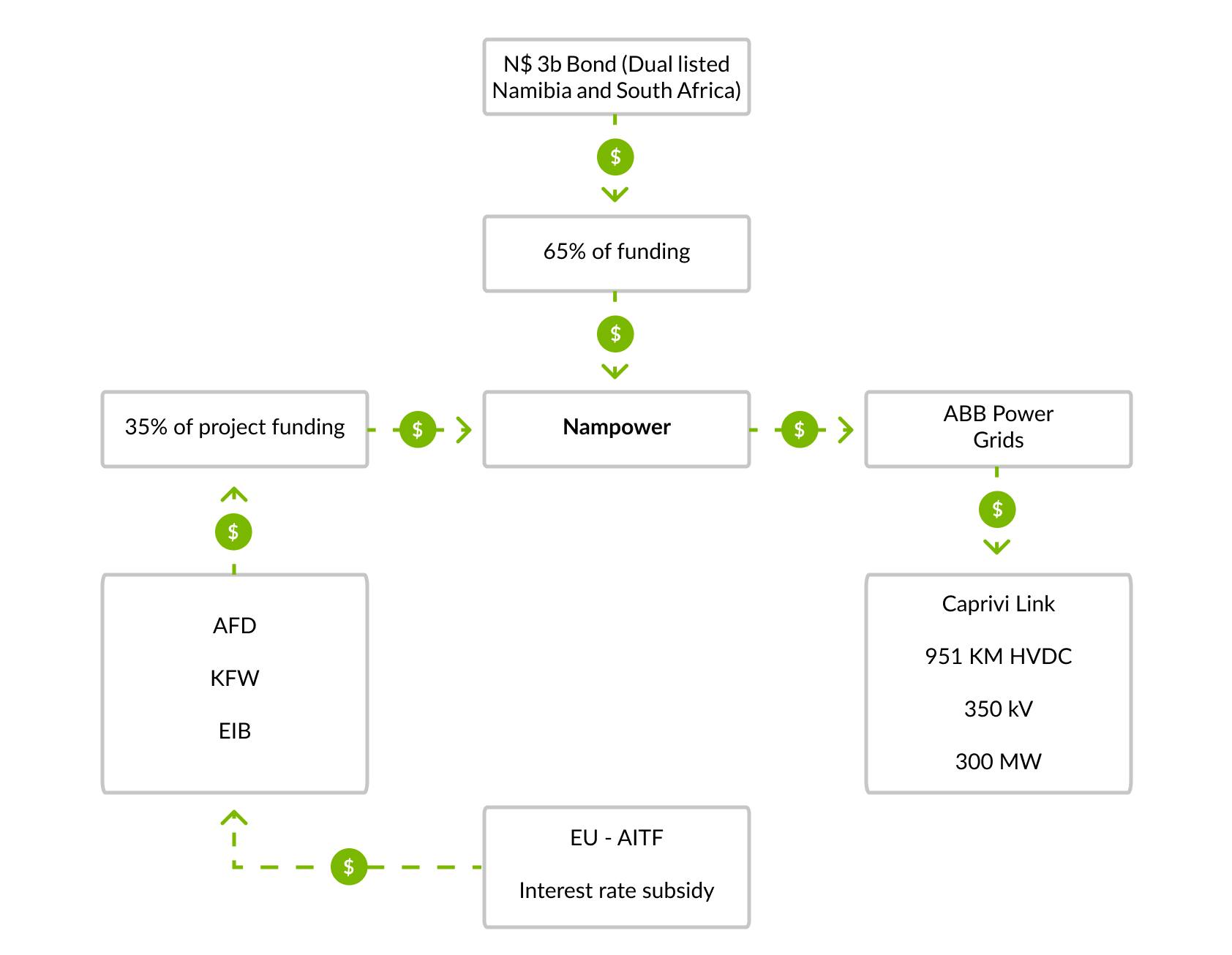

Further, a creditworthy power utility responsible for transmission assets may choose to raise a corporate bond from capital markets for general-purpose borrowing, and then use a portion of those proceeds for investment in new, or the rehabilitation of existing, transmission infrastructure. An example of state-owned utility capital market borrowing is provided in the following case study.

Case Study — Caprivi Link InterConnector

NamPower, Namibia’s national power utility, is responsible for generation, transmission and energy trading, reporting up to the Ministry of Mines and Energy. Its favourable and independent financial credit rating has allowed it to raise financing from the capital markets for its long-term projects.

In 2007, NamPower successfully dual-listed a $3B Namibian dollar-denominated long-term debt issue on both the Namibian and South African stock exchanges to fund the Caprivi Link Interconnector connecting Namibia to the Zambian and Zimbabwean electricity networks by 2009. Notable features at the time included a 300MW bipolar scheme, upgradeable to 600MW, and comprising a 951 km 350kV high voltage direct current (HVDC) bipolar line, along with numerous substations. This represented the first cross-border debt-raising transaction completed in Southern African capital markets, to finance a cross-border interconnection in line with the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) with the objective to interconnect all Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries.

Government-supported financing is the most common approach to financing transmission infrastructure projects in Africa. Government balance sheet financing supports infrastructure ownership and controls being retained by the government and/or the relevant transmission utility, thereby increasing the asset base of, and sources of revenue, for the country. In addition, the government or the transmission utility remains in full control of the technical designs, timelines and process in the development of the transmission infrastructure.

Where the transmission utility maintains ownership of the transmission infrastructure, it also bears the risk and responsibility for the proper management and maintenance of the infrastructure. This extends to:

This often results in significant reserves being required to meet the costs of such obligations.

Public sector-led funding structures will affect the balance sheets of both the government and the utility. Such funding structures also affect the extent of the government’s debt sustainability. Hence, these structures require significant fiscal discipline.

There are examples of transmission infrastructure that is built by an IPP developer as part of a generation project. Generation power projects tend to be located as close as possible to fuel sources (river, coal mine, solar radiation, etc.). However, especially for renewable projects, the fuel sources are often far from existing grid connections and may require the construction of additional transmission infrastructure including substations. When procuring a new generation project, the government or the transmission utility may therefore decide that the transmission infrastructure is to be built by the IPP as part of the broader generation project and handed over to the government. Depending on the developer’s appetite and the size of the transmission line asset, the IPP might be interested to accept to take on the construction (and potentially financing) of a transmission line that will connect its project to the grid. Nonetheless, since the transmission line is transferred to the utility at some point in the project, the transmission line is ultimately will be government-owned.

This kind of model is used to reduce the connection risk in IPP projects. This ‘connection risk’ is the risk that the IPP or power plant is producing (or able to produce) electricity but cannot deliver it to end users because of a lack of connectivity to a transmission line. This could manifest itself in the construction phase of the power generation project where the delay in the construction and completion of the transmission infrastructure in turn delays the achievement of an anticipated commercial operations date under the power generation project.

This model allows the IPP to be in control of the interface risk between the two projects — generation and transmission. If this risk is not managed in this way, the typical remedy to the IPP is the inclusion of “deemed energy” payments under the power purchase agreement. These are payments calculated based on the loss of revenue from the energy that would have been delivered but for the transmission line unavailability event. Where generation is in the private sector but transmission is in the public sector, there is an increased financial risk on the government to pay these “deemed energy” payments (e.g., see above Case Study — Lake Turkana Transmission Line) to the extent the government or transmission utility does not manage or deliver the transmission infrastructure or make it available for the IPP to use.

The extra equity investment and debt funding necessary for the supplemental transmission work can either be repaid via a cash payment by the transmission utility when the transmission infrastructure is handed over or can be compensated through a higher generation tariff which reflects the additional fixed cost incurred to connect the power project to the national grid. The transmission asset will typically be handed over to the transmission utility at the commercial operation date, even if the cost of the construction is repaid to the IPP through the electricity tariff under the PPA.

Some considerations that arise when transmission infrastructure is built and captive to the benefit of one beneficiary (closed access for other usages) but which is ultimately handed to the transmission utility to maintain via public funds, is whether the transmission line still serves the greater public good. This may still be the case if the captive line provides reliable electricity to industrial users, who have wider economic benefits for a country.

Case Study — Self-build funding model in the South African IPP programmes

The South African government, through its energy ministry, has undertaken the competitive procurement of many independent power producer (IPP) programmes across various technologies since 2010. One of the most lauded of these programmes is the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP). Today REIPPPP is in its fifth round of procurement. As of the end of round 4 bidding, the South African power utility Eskom Holdings SOC Limited (Eskom) concluded PPAs for 92 renewable energy projects with a total capacity of 6327 MW. Grid connection and integration of the power generation facility to the national grid was a key feature of the REIPPPP.

Facing Eskom funding constraints and the short timelines required for grid connection, the REIPPPP was structured to allow bidders to elect to build the grid connection facilities on a "self-build" basis as part of their bid. The option was initially only made available for distribution facilities but in the second quarter of 2015, Eskom's transmission division introduced a self-build option to its customers, both electricity generators and consumers.

In this option, the customer can elect to design, procure, construct and commission the transmission assets. The customer undertakes the design, route selection and procuring of all authorisations, with consultation and the approval of Eskom, who ultimately ensures the transmission infrastructure aligns with existing grid technical specifications. After successful commissioning, the customer is obliged to transfer full ownership of the transmission assets and all environmental authorisations, wayleaves, approvals and permits to Eskom. Eskom states in its Transmission Development Plan published in January 2021 that the intention is to give customers greater control over risk factors affecting their network connection. However, it is important to note that transmission infrastructure expects that it is open access, meaning there could be the possibility of connecting other generation assets and other customers to the self-build transmission line after it is handed over to Eskom.

The self-build option has since also been expanded to allow customers to also build associated works (such as substations) that will be shared with other customers, based on an assessment by Eskom of the accompanying risks to the transmission system and other customers. Since this is purely a voluntary option, the option of Eskom constructing the generator or customer's network and paying a connection charge also remains available to bidders and customers alike.

What is important to note with this option is that the customer bears the risk and responsibility to finance the transmission infrastructure construction works, including the authorisations required and the wayleave acquisition (including compensation). These costs are recovered through the tariff over the term of the PPA, so IPPs need to consider these additional costs when bidding into the tender.

Due to the success of the self-build option, this approach has been adopted by the South African government in all subsequent IPP programmes.

This chapter will discuss the Independent Power Transmission (IPT) model, the scope of which involves the design, construction, and financing of a single transmission line or a set of transmission lines and/or associated transmission infrastructure such as substations. The IPT models described below assume transmission assets that are connected with the country’s wider electricity network rather than captive assets for the benefit of an industrial offtaker (which are discussed in chapter 7. Other Private Funding Structures). Although an IPT is typically used for the development of greenfield assets, we will also explore how the same concepts can be used for the refurbishment of existing transmission assets.

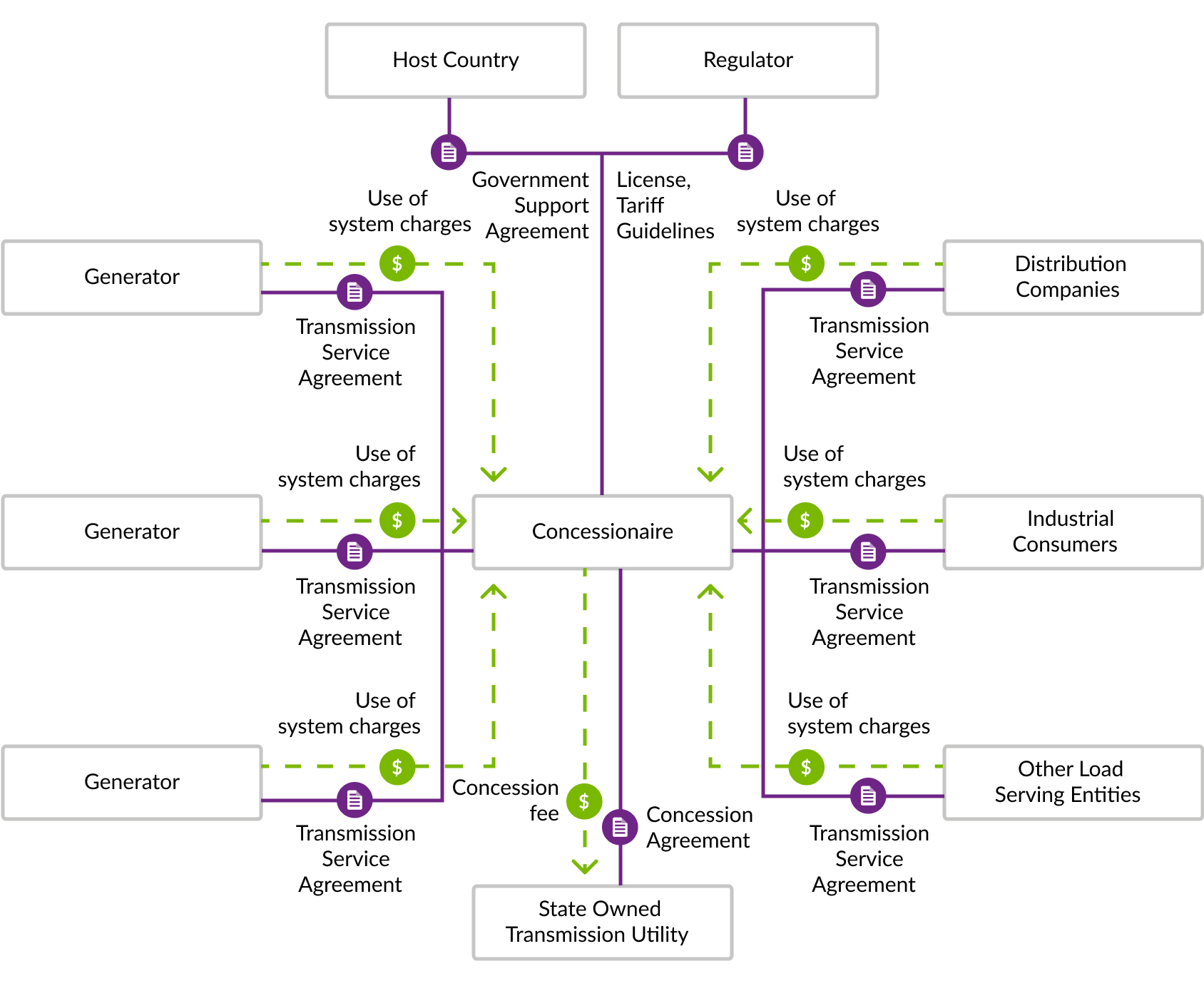

In emerging markets, IPTs are implemented under a long-term contract, generally between the state-owned transmission utility and a project company. The contract will typically define the economic payment model, and the roles and responsibilities for the new infrastructure, including ownership, construction, maintenance and financing responsibilities. These contracts can be structured as transmission service agreements (TSA) but may also take other forms such as lease or line concession agreements. In this chapter, the long-term contract will be referred to as a TSA although it might have another name in practice.

IPTs have a proven record in many countries across the world including Latin America and Asia. They are often described as a less disruptive intervention in the transmission sector than the other available private business models as they typically can be implemented with limited or no regulatory reform. The IPT model, therefore, has the potential to unlock many critical infrastructure projects in SSA and, if well structured, could help African transmission utilities quickly finance lines that have a direct and positive impact on their revenue.

There are a handful of different IPT business models which have successfully resulted in transmission infrastructure built, maintained and financed by private project companies. While very similar, in that the private party assumes construction and financing risk in all IPT models, they vary by degree of ownership and maintenance obligations which will normally change the terms of repayment and the risk allocation between the project company and the transmission utility. The return on investment expectations, as well as the cost of financing, will increase the more the project company bears risks that condition its repayment.

“Operations” — Line operation and maintenance or system operation

“Operations” in this chapter refer to specific maintenance activities required to ensure that a transmission line and other associated infrastructure are available to be used when specified. This is different from “System Operations'', which is carried out by the transmission utility/transmission system operator (TSO) on a whole network basis and involves system control and dispatch of generation facilities. Notwithstanding the IPT model used, system control and dispatch will be carried out by the transmission utility/TSO, not the project company. Hence, in this chapter, operations refer to “line operation & maintenance” only.

The TSA establishes the financial terms and period during which the project company is entitled to receive payment in exchange for ensuring the constructed transmission infrastructure is available to be operated by the transmission utility as specified. In most cases, the project company will not take demand risk (volume or price), or utilisation of transmission infrastructure risk, since the transmission utility will determine how, when, and by what means the grid is managed and electricity is dispatched. The simplest way of structuring TSA payments is as a fixed return on investment amortised over the term of the TSA, structured as a service charge with scheduled payment dates. This type of annuity (or unitary payment) very clearly defines the revenue stream by which investors and lenders can recover their respective capital injections, which should lower lenders’ cost of capital and investors’ return expectations. Also, when the transaction is structured appropriately, the annuity payment becomes the key criterion for selecting the winning bidder, assuming of course that competitive bidding is used.

The annuity payment will be sized to ensure the project company can recover expenses associated with capital expenditure, financing and operating and maintenance agreement (O&M) expenses related to constructing, financing and, if applicable, operating the transmission infrastructure. Depending on the IPT business model, there may be an element of payment variability associated with asset performance linked to O&M obligations. However, baseline payment will be sized to ensure ongoing debt servicing. Below are the most common IPT business models:

In most IPT models that have been successfully implemented to date in Latin America and Asia, the private ownership of transmission-related assets is transferred to the transmission utility at the end of the TSA term.

BOOTs used extensively in Latin America

38 projects implemented in Brazil (220kV lines for a total of 50,000 km) and 18 projects in Peru (220kV and 500kV lines for a total of 7,560 km) were BOOT.

There are some countries in SSA that have the regulatory environment or experience with IPPs to be able to implement IPT business models within existing legislation. For countries with a track record in IPPs, IPTs could be considered a logical next step in using private capital to develop and expand their electricity networks. Many of the same government stakeholders who are familiar with the process and requirements of an IPP are likely to have the capacity and relevant experience to enable IPTs, especially when generation and transmission are bundled under the same utility.

In many countries, a transmission licence will need to be granted to the project company, either by a regulator or other relevant authority. There may also be a legal prohibition on private companies owning and operating transmission infrastructure (e.g., due to concerns about the natural monopoly characteristic of transmission infrastructure). If there are legal prohibitions, then there may be ways to structure around this as described in the section below (Ownership of transmission assets). If this is not possible, then an IPT business model can only be implemented if the regulatory structure is amended to allow the granting of a licence or appropriate authorisations by the regulator or relevant authority.

A regulator will typically have a role in approving (and likely licencing) the project company to implement a specified IPT business model. Thereafter, the regulator is likely to be responsible for monitoring compliance with licence conditions, which could include identified KPIs under the TSA during the O&M phase. When the TSA includes a simplified payment model, which eliminates demand risk, the regulator will typically wish to understand and approve the payment model. Before a TSA is being agreed to, the regulator needs to understand the cost and benefit to the sector but will not need to review complex tariff methodologies periodically during the TSA as required with power generation projects.

There are three key phases of an IPT project:

See chapter 9. Planning and Project Preparation for a description of the planning process of transmission projects. Project selection is critical in determining which transmission infrastructure is suitable for an IPT. Some of the key criteria to examine include:

The economics of the relevant project will have to be analysed based on the available data on the sector’s financial viability and growth prospects, and a set of assumptions. Projects that deliver the following efficiencies are well suited for an IPT business model: (i) can be delivered faster with lower O&M costs by the private sector, and (ii) likely to improve the sector’s cash flows by increasing the network’s availability (e.g., by connecting new end users to power supply, thereby meeting unserved demand). These types of projects are generally identified during the power system planning phase.

An analysis of whether there are other funds in the budget at the national, ministerial, or utility level for the financing of the infrastructure should be completed. The government should also assess whether there are donor funds readily available to procure the project without it being an IPT — if this is the case, some efficiencies from the private sector’s ability to maintain and operate the asset at a lower cost may be lost. If some alternative funding sources are identified, the government should then decide whether the transmission infrastructure is the best use of these funds.

An IPT is unlikely to be a suitable solution for smaller projects. Typically, for projects less than US$50 million, given the expense required for project preparation and execution, an IPT may not be the most suitable method of financing. It should be noted, however, that a series of smaller projects can be aggregated into a portfolio and executed as part of a single IPT investment.

An assessment of the overall legal and regulatory regime will be key to identify any particular challenges with an identified project. Environment and social risks should also be considered early to avoid obstacles that might stifle the financing efforts at a later stage (e.g., the construction of a transmission line through a protected natural reserve). This is not to say that easy projects should be implemented through the IPT model, but it would be wise that the first IPT project does not have added complications, as implementing a privately financed transmission project is challenging enough in a country with no relevant experience.

The host country can decide to allocate a project to a developer at an early stage in the project’s development or to undertake a certain level of preparatory work first. Allowing the developer to take responsibility for early-stage preparation provides more flexibility and may result in more innovation and cost savings. It also relieves the government from raising funds for project preparation and requires less capacity and government resources, although external funding may be available for conducting feasibility studies by the government or by the private sector. On the negative side, the developer needs to be selected before the design and investment requirements are finalised.

Countries can also choose to carry out a certain level of preparatory work centrally before conducting an auction or tender process to attract a greater level of investor interest and procure the most cost-effective construction solution and lowest cost of financing. While effective, this approach requires more resources initially to manage the project preparation phase until the developer is selected. Further detail on choosing between these approaches can be found in the Understanding Power Project Procurement handbook.

Regardless of who will be responsible for each activity, the following workstreams need to be completed during the preparation stage:

The development phase will end when the project reaches “financial close,” i.e. when all conditions precedent to the disbursement of the debt required for the project have been met, and monies disbursed.

After a financial closure has been achieved, construction will begin. The project company will typically be responsible for managing the project activities required to complete the infrastructure, although in some instances there may be a third party acting as construction manager. Even in the case of a single contractor (EPC), an owner’s engineer will typically be retained to supervise all aspects of the project and advise the project developer/owner. Some financial institutions may employ their own engineers and legal advisors to monitor construction, in particular the environmental and social aspects. Lenders will typically disburse their loans to fund the construction of the assets during this phase, although in some cases the equity investor in the project company may decide to finance the construction phase and refinance once the asset is built and delivered.

Generally speaking in IPT models, the control and dispatch of power will be the responsibility of the transmission utility acting as TSO, given the interface with the wider network. It is possible, but rare, for the private sector project company to take operational control of a section of the transmission network. Maintenance of the asset, which may include some localised operational activities, may be the responsibility of the project company. The project company may decide to have its own staff or hire a contractor to undertake this maintenance. In some cases, maintenance will be the responsibility of the transmission utility, either under the terms of the TSA or because the project company contracts back to the transmission utility under a maintenance agreement. The role of the project company in this respect has an impact on investor risk and is likely to determine the most suitable payment model that is agreed between the project company and the transmission utility (or an alternative offtaker). The decision as to which party is responsible for the maintenance and/or localised operations is a function of the risk analysis and how the project fits into the overall system strategy of the government.

The roles of each relevant sector participant concerning an IPT are set out in the table below.

|

Sector Participant |

Role |

|---|---|

|

The project company will have at least one shareholder/equity sponsor. In the case where projects are allocated earlier in the process, the owner of the project company will probably also develop the project. The developer will then either fund the project company with sufficient equity to capitalise it in the long term at a financial close or it will bring in a new shareholder. As with the IPP sector, developers usually carry out work and fund early-stage activities “on risk” in consideration for earning development fees, which are typically paid at financial close. Among the other project development activities undertaken by the developer/equity sponsor, it will take responsibility for arranging debt finance for the project company. During the lifetime of the IPT investment, the developer/equity sponsor will manage the project company and be the key point of interface between the project company and the stakeholders. |

|

Lenders will finance the project company with loans. They will typically be mandated during the development phase to review the contracts developed by the developer/equity investor and test their “bankability” ahead of financial close (see below). At the financial close the lenders will fund the project and their loans will be drawn down to fund construction. IPT lenders include MDBs, bilateral DFIs, ECAs, and donor agencies. To provide long-term lending, international commercial lenders will likely only be able to participate with some kind of political risk or credit insurance from an ECA or DFI. Some local funding may be available as part of an overall funding package. |

|