2

Financing Structures and Capital Sources

Introduction

The business models used to finance transmission infrastructure are heavily impacted by sources of funding for the sector. Before introducing the different business models, it is necessary to understand the various external funding options and their criteria, which this chapter explores.

In the next chapter 3. Common Funding Structures in the African Market, we discuss the status quo of transmission infrastructure financing in the African continent — the public sector structures generally used to finance these types of projects at present. We then look to business models involving the private sector in chapters 4. Introduction to Private Funding Structures, 5. Independent Power Transmission (IPT) Projects, 6. Whole-of-grid concessions, and 7. Other Private Funding Structures.

Transmission projects will go through a detailed planning phase before a source of financing and a business model are selected. Chapter 9. Planning and Project Preparation explains this process.

The risks highlighted in chapter 11. Common Risks must also be considered as these will impact sources of funding as well as business models. The funding decision will have implications for the introduction of the private sector or continued reliance on public sector funding, and together these will inform the business model selected.

Below we set out the broad principles of financing that have been or could be applied to the funding of existing and future transmission infrastructure projects.

Corporate Finance

Many businesses, especially large businesses in capital intensive industries, raise debt funding on the strength of their balance sheets, the stability of their revenues, and their ability to service their debts. They do not grant security over any part of their assets to lenders or bondholders, and they agree with each lender that they will not grant security over their assets to any other or future lenders. This type of financing — financing that does not involve the grant of security over a company’s assets — is referred to as corporate finance.

When considering corporate finance in the context of funding transmission infrastructure, the relevant entity procuring funding has historically been the national transmission company of the country. The financial health and liquidity of this entity’s balance sheet (assets and cash flows) will determine its borrowing capacity (which can be enhanced with government support). If the credit of the national transmission company does not allow it to raise debt, additional support from the government’s balance sheet will be required to secure external debt.

Project Finance

In a project finance context, the funding is secured against the viability of a specific project. In this option, a project company is created for financing, constructing and potentially operating the transmission assets and is financed with a mix of equity and debt. In typical project finance funding structures, the project company also retains ownership of the transmission asset. A lender considers the revenue generated by the transmission project as the primary, and often singular, source of loan repayment. The projected cash flows after meeting operating expenses must be sufficient to service debt in terms of capital repayment and interest. The cash flows available after debt service should also provide a reasonable return on equity.

The predictability, sufficiency and certainty of cash flows will determine the project company’s borrowing capacity to finance the project. If the project underperforms and the borrower defaults on the loan as a result, the lender will have the right to enforce its security on the project company’s assets. If liquidating the project company’s assets is insufficient to recover the balance of loan owed due to default, the lender will have no recourse to the owner(s) of the project company for further compensation: the sponsor's liability is limited to the investment it has made via its equity contributions. Therefore, the key to project finance is the underlying revenue stream generated by the asset in question (e.g., annuity, use of system or wheeling charges for a transmission infrastructure project).

If the transmission asset is not linked to a dedicated generation facility or a large industrial consumer, and there is uncertainty as to how well-utilised the transmission infrastructure will be, lenders will expect a payment regime similar to a fixed capacity payment or fixed availability payment. Such payments are not vulnerable to changes in the amount of power flows on the transmission line.

Corporate Vs Project Finance

Balance sheet flexibility

In the context of transmission infrastructure, an entity’s borrowing capacity via corporate finance is limited by its existing balance sheet, including how much existing debt it has (and the state of its revenues and assets). Any existing balance sheet constraints will limit the borrowing capacity of transmission utilities to fund transmission infrastructure using corporate finance structures. The state utility may have the opportunity to borrow further with government support. Project finance structures, however, do not look at the transmission company’s borrowing capacity because the debt capital raised is treated as off-balance-sheet financing.

Cost of funds

Under corporate finance, since repayment is divorced from a transmission asset’s underlying economic value or performance, repayment risk will be a function of a borrower’s existing level of leverage compared to the financial or market value of its total assets to determine its liquidity. A healthy balance sheet will attract a lower cost of financing (more efficient pricing). As the credit quality of an entity decreases, the cost of funding increases due to higher risk perception.

Under the project finance option, since repayment is secured via project revenue, lenders will focus on mitigating all risks to those cash flows. Project finance transactions tend to be highly structured and complex, with emphasis placed on appropriate contractual allocation of risks that impact the underlying revenue stream. This adds to the time and cost of pulling together the number of stakeholders and related documentation. The pricing of the project is influenced by the perceived risk of the cash flows, the credit quality of the source of those cash flows, and if needed, the enhancement of these cash flows.

Business model considerations

Transmission networks require ongoing investment. Ongoing investment requires continuous capital injections in the business in the form of new projects or upgrades of existing assets. As a general rule, state-owned transmission utilities, whole-of-grid concessionaires, or privatised utilities will typically find it more practical to raise debt financing using corporate financing techniques. In contrast, a project company established to implement an independent power transmission (IPT) project will use project finance to allow for higher debt to equity ratios, longer tenor, and limited recourse for the shareholders in the project company. Given these factors, IPTs are likely to be financed using project finance techniques.

Sources of Capital

The sources of capital for a transmission project will depend upon the outcome of the planning, risks related to the project, and a government’s and state utility’s balance sheets and the ability to raise finance. In chapter 3. Common Funding Structures in the African Market, the existing model of government balance sheet financing for these assets is discussed in more detail, and in later chapters, we discuss some private sector finance models. Below, we set out the typical capital sources — government budgetary allocation, debt, and equity — and indicative terms used in most funding models.

Government budgetary allocation

In the context of its annual budget, a government may choose to allocate a certain amount of the fiscal budget to the development of the country’s transmission infrastructure. When an allocation is made, the specific method of application of these funds is likely to vary from one government to another depending on the country’s laws and conventions for public procurement of infrastructure. In some jurisdictions, the funds will be managed and applied directly by the Ministry of Energy (or equivalent); in others, they may be channelled via a department of public works or the state-owned entity licensed to construct and maintain transmission infrastructure. Nonetheless, the source of these funds will invariably come directly from the government’s accounts or “balance sheet” as shown below, and thus the government’s ability to finance transmission infrastructure through a budgetary allocation will depend on the country’s priorities and fiscal constraints. Ultimately, the decision as to whether to use this model will depend on the government’s balance sheet (i.e. availability of cash) and its expenditure priorities (based on its current policies) given a country’s wider infrastructure investment needs.

In practice, financing transmission infrastructure through budgetary allocations is difficult and has become increasingly rare. The size of the investment puts significant pressure on a government’s budget and its available cash. The allocation can be structured in a way as to accumulate yearly until reaching the required amount, but depending on the size of the investment, the desired amount may take many years to be collected. Furthermore, in addition to slowing down the development of the power grid, this approach requires significant fiscal discipline as the government needs to set aside the funds each year and resist the temptation to use them when a crisis or economic downturn arises.

Debt

Transmission infrastructure necessitates long-term funding, given the relatively high capital expenditure required for identification, development and construction. Given constraints in local commercial banking markets, public financial institutions are an important source of debt financing for transmission infrastructure.

The stakeholders and financial products described below cover both public and private sector debt financings — their application in real-world scenarios is dealt with in later chapters.

Concessional funding for balance sheet financing

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and donor-backed funds can lend directly to governments on concessional or grant terms for identified projects which follow the MDB procurement guidelines, and can also be lenders for the financing of independent power transmission projects in the private sector.

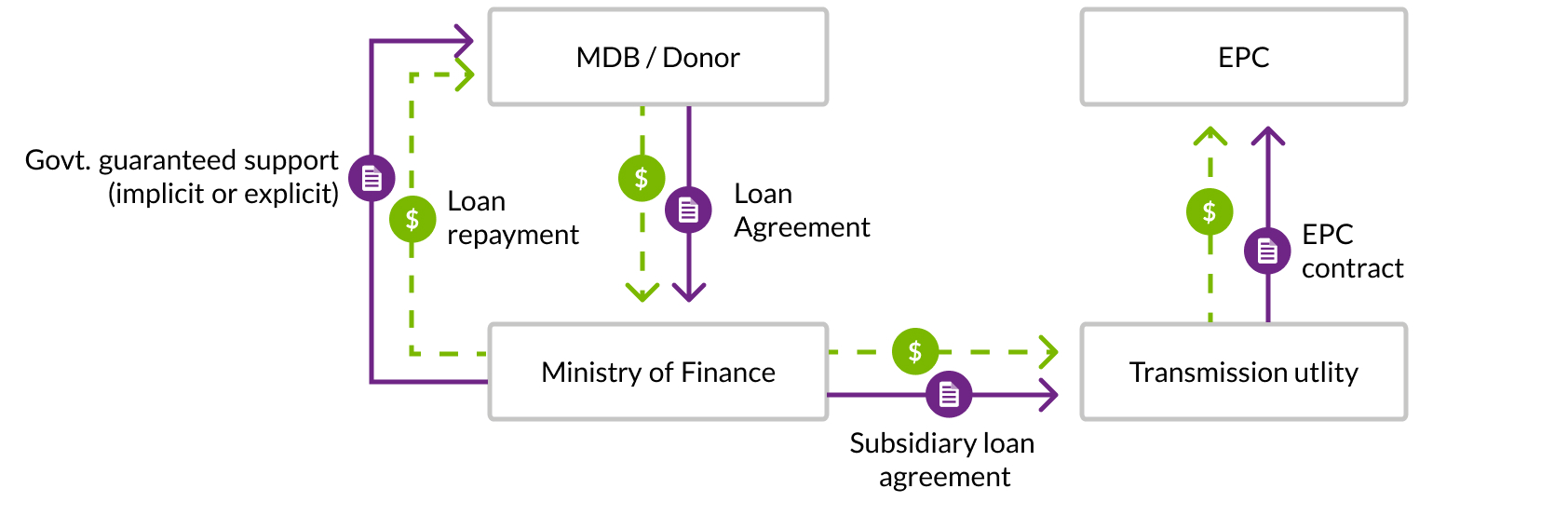

Examples of MDBs, which provide concessional finance, include the African Development Bank, European Investment Bank, and the World Bank Group. Concessional in this context means that the terms of the loan are likely to include low or subsidised interest rates, extended grace periods, and long amortisation schedules that can extend beyond 30 years. Typically these loans are provided to the government via the Ministry of Finance, and on-lent to the transmission utility. These loans are accounted for on the government’s balance sheet, typically as both an asset and a liability. The transmission company will own the asset, but repayment, if required, will be secured from the government's balance sheet. MDB and donor concessional money may be used to settle contractor invoices directly, but the government remains the obligor.

Transmission projects funded through MDB concessional funds can in some instances take longer to secure the funding and the necessary contractors. This is often the case where the government or the utility does not have the necessary capacity to manage the high degree of coordination, planning, and adherence to MDB procurement guidelines for such projects. In addition, MDBs have country and sector limits (often called “funding envelopes”) that are available to countries for this type of financing support which get revised based on the country’s capacity for debt and the requirements of the ministries. When the funding envelopes may be nearing their limits, countries will have to prioritise the infrastructure projects they want to support. Bilateral donor agencies can be another source of grant or heavily subsidised financing which can provide sector viability gap funding or support to an individual transaction.

Private sector MDB funding

The same MDBs have “private sector windows”, i.e., funding available for private sector projects, such as IPTs. These are loans granted on commercial terms rather than concessional terms, and for tenors up to 18-20 years. Importantly, private sector MDB loans are not captured on the government’s balance sheet, unless a government guarantee or financial backstop helps secure repayment. The structures under which MDBs participate in IPTs are set out further in chapter 5. Independent Power Transmission (IPT) Projects.

Export Credit Agencies (ECA)

Export Credit Agencies (ECA) are institutions that are publicly owned financing agencies that help finance national exports by providing direct loans, guarantees, or insurance to overseas buyers, including entities such as transmission companies. ECA finance can be used in the public sector, in government balance sheet financing, and project finance involving IPT structures.

Examples of active ECAs in Sub-Saharan Africa include the Export Credit Insurance Corporation of South Africa, US Export-Import Bank, UK Export Finance, BPIfrance, SERV from Switzerland, Euler Hermes from Germany, and the Export-Import Bank of China. Some of these agencies can provide local currency solutions in certain jurisdictions, but for the most part, provide USD and Euro denominated loans.

To ensure financing discipline and promotion of fair and transparent trade practices, financial terms and conditions follow guidelines set by the OECD, called the OECD Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits guidelines. Eligible financing is typically up to 85% of the relevant export contract, with some allowances to cover a portion of local on-shore costs, but the expectation is that the government (or borrower) covers the 15% balance, usually in the form of a down payment in cash. Financing terms include longer tenors than commercial banks can competitively price or sometimes provide to borrowers in certain jurisdictions (up to 12 years for corporate finance and 14 years for project finance loans), but the cost of funds is generally more expensive than concessional borrowing. For transmission infrastructure associated with a renewable energy generation project, the OECD Arrangement allows project finance loans up to 18 years, on an exceptional basis.

In the context of transmission infrastructure, ECAs can provide (1) corporate finance loans, underwriting the sovereign’s capacity to repay the loan, lending directly to Ministries of Finance, which helps to reduce the cost of financing, and (2) project or corporate finance loans to IPT special purpose vehicles (SPVs) or private companies, respectively.

Depending on the ECA, they can either lend directly or insure/guarantee (between 95-100%) a commercial bank that will provide funding, which will be reflected in the commercial bank’s lower cost of funds to the project.

Development Financial Institutions (DFIs)

Development Financial Institutions (DFIs) which include MDBs, are usually majority-owned by national governments and source their capital from national or international development funds, or benefit from government guarantees. This ensures their creditworthiness, which enables them to raise large amounts of capital from international capital markets and provide financing on very competitive terms. DFIs can provide up to 15 to 20 years, long tenor competitive commercial lending to projects with some degree of private ownership. Some examples of DFIs active in Sub-Saharan Africa include the Development Bank of South Africa, Development Finance Corporation from the US, the CDC group from the UK, Proparco from France, and FMO from the Netherlands.

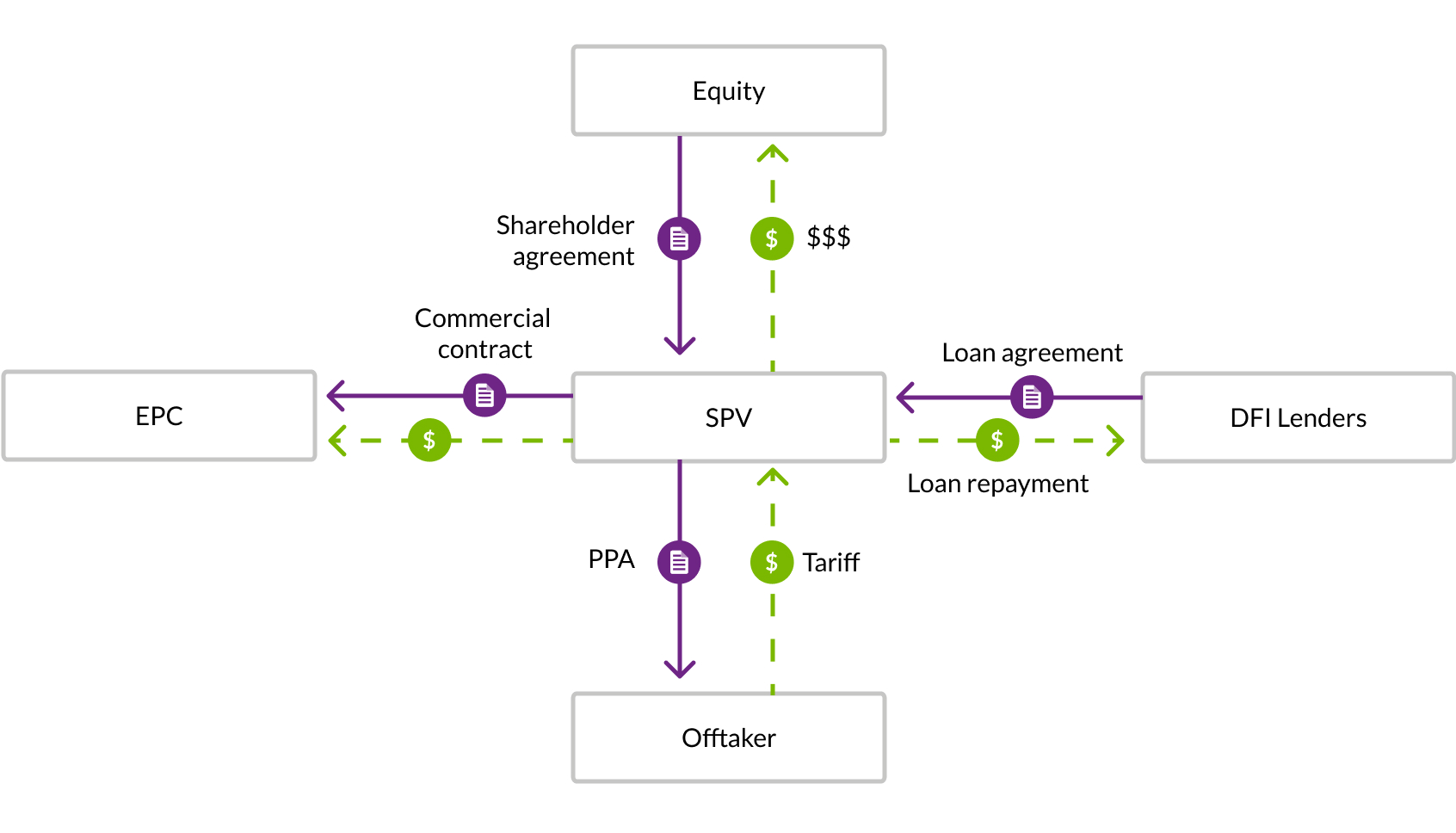

Some DFIs can provide loans to state-owned utilities which demonstrate independent governance, depending on that utility’s balance sheet and ownership of assets. All DFIs can provide commercial project finance debt to a project company, which can be used in IPT transactions. The diagram below shows a DFI-funded project finance structure.

In addition to lending, some DFIs such as the AfDB and the WBG can

offer a guarantee and insurance products to help credit enhance a

project structure by covering off certain credit or political risks.

Guarantees include partial credit guarantees (PCGs) and partial risk guarantees (PRGs) to cover commercial lenders and investors against the risk of a

possible government failure to meet contractual obligations to a

project. Please see the

Some DFIs provide political risk insurance (PRI) to mitigate and manage risks arising from the adverse action, or inactions, of governments that go against contractual obligations. PRI can also be used to backstop termination support under a government guarantee or other forms of government undertakings if the government is unable to pay as per its contractual obligation.

Green/climate-backed financing

There are many clean technologies and climate change donor-backed funds which can provide grant funding to support grid modernisation and transmission lines, if the infrastructure can be linked to projects and initiatives which promote and advance sustainable development and encourage the development of a more sustainable economy, for example, renewable energy generation. Given the emphasis that many countries are placing on decarbonisation to support countries on their journey to a green energy transition, it is expected that the EU and other publicly backed institutions will make more grants or highly concessional finance available to support these activities.

The advantage of these resources is that they provide subsidised financing, which, when combined with more commercial sources of funds, can help blend the cost of capital to reduce financing costs for transmission infrastructure.

Transmission is the enabling infrastructure for renewables, and, as such, it should be credited with greenhouse gas reductions and be eligible for green financing. In addition, the strength of the existing transmission and grid networks will determine how much greenfield renewable energy generation a country can support. Many emerging countries with mandates to significantly scale up renewable energy generation will need to simultaneously invest in upgrading and expanding their transmission network to support greater renewable energy penetration. While this is still an evolving field, greenhouse gas reduction calculation methodologies have been considered by numerous organisations and both governments and developers should monitor progress to identify potentially attractive financing options.

Commercial Banks

In addition to DFIs, commercial banks provide debt financing to transmission infrastructure projects. Commercial banks are privately owned banks that participate and provide funding to a range of projects, including transmission projects. Commercial banks more typically lend to projects that have creditworthy cash flows or cash flows that are enhanced with cover via DFIs or ECAs.

Typically, commercial banks are financial institutions that are regulated by central banks and other international banking regulations which impact the level of liquidity, risk thresholds and pricing.

Blended finance

Providing hybrid private sector/donor funding for IPTs, for example, can significantly boost the availability of funding to the sector. The provision of grant funding for a project is unlikely to impact returns for investors positively or negatively since funding models for this asset class are typically fixed or capped. The impact of such funding would be to increase the number of projects which can be undertaken.

Equity

In IPT and other project finance structures, lenders generally require project owners to invest an amount of equity in exchange for shares in the project company, usually for at least 20-30% of the total project cost. This form of long-term capital earns dividends over the life of the project which are paid from the remainder of cash flows after operating expenses and debt service obligations have been met. The capital structure and cash waterfall are intentionally aligned so that equity owners are incentivised to ensure that the transmission assets are constructed and perform as contractually specified, to generate and collect the forecasted revenue. Equity providers for transmission infrastructure include:

- Developers/Contractors: This includes developers or engineering, procurement and construction (EPC)/original equipment manufacturer (OEMs), who develop, build, and/or operate transmission assets and are interested in providing equity and/or subordinated debt in an underlying project if the long term economics are sufficiently attractive.

- Infrastructure funds: There are many infrastructure funds or DFI-funded investment vehicles with a mandate to invest in the energy sector, which can include transmission infrastructure.

- Development Finance Institutions: A few DFIs can provide equity funding for various types of power projects so long as the long term economics are sufficiently attractive.

- Industrial sponsors: This includes sponsors who invest in the construction of dedicated-use transmission infrastructure to support their core business or power generation plants, such as mining companies.

In some instances, state-owned transmission companies or energy utilities also invest capital (or some other form of consideration) into a project company and acquire equity interest.

Summary of Key Points

- Corporate Finance is a way for an entity to secure an external debt by leveraging its balance sheet. The financial health and liquidity of the entity’s balance sheet will determine its borrowing capacity.

- Project Finance allows an entity to raise external finance on a non-recourse basis where loan repayment is secured by cash flows generated by a project company’s assets.

- Key considerations between raising debt via corporate or project finance structures include (1) creditworthiness of the obligor, which will determine the cost of funding and whether additional payment security is required, and (2) business model procurement strategy.

- The most traditional source of capital to fund transmission infrastructure has been the government’s balance sheet.

- Sources of external funding to support government borrowing include bilateral donors, MDBs, and ECAs.

- External funding for IPTs and whole-of-grid concessions include DFIs and ECAs, along with commercial banks, generally with some form of credit enhancement from DFI or ECA guarantee or insurance product.

- Green/Climate-backed financing can provide meaningful blended finance and viability gap funding for grid modernisation, critical for emerging markets who need to strengthen their transmission and grid networks to support greater renewable energy penetration.

- There are providers of equity in the power generation space who could provide equity in IPTs assuming the economics and returns of the project are sufficiently attractive.

- External funding sources and their criteria can impact the business model a government chooses in procuring new transmission infrastructure.