3

Common Funding Structures in the African Market

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to set out, in a non-exhaustive fashion, some of the common methods of funding transmission infrastructure that are currently used on the African continent and to highlight some of their features.

Most of these funding methods are public-sector led. However, they are akin to corporate finance structures as the financing is based on the strength of the government or state-owned utility balance sheets and not on the viability of the cash flows from the transmission projects specifically. These methods include government borrowing/ECA financing and state-owned utility borrowing. Of these methods, government borrowing and ECA solutions (which also require a government guarantee) are by far the most common funding structures utilised.

The most common private sector-led funding method used for transmission projects on the continent is the wrapping up of the financing of the transmission project into a related IPP project. This method, discussed in this chapter as the generation-linked transmission model, is the closest to project financing for transmission projects on the continent. As will be discussed in detail in this chapter, the cost of the transmission project is included as part of the construction costs of the IPP project. Since the IPP project is funded using a project financing structure, the costs of the transmission project are typically recouped from the cash flows of the IPP project.

Public Sector-led Funding Structures

Government borrowing

From one country to another, the names of ministries are likely to vary and their functions can be separated differently among fewer or more ministries (e.g., the functions of the Ministry of Finance in one country may be shared between the Ministry of Economic Planning and the Ministry of Finance in some other countries). For this chapter, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) refers to the ministry (or ministries) responsible for raising and collecting both foreign and domestic revenues, managing the budget process and cash resources, setting fiscal policies and forecasting government revenues. The MoF is also responsible for borrowing on behalf of the government and managing the purse strings, which sometimes requires limiting the spending by which ministries try to deliver on their respective policy goals.

In a funding structure using government borrowing, the MoF effectively serves as the borrower on behalf of the government. The borrowed funds will be used for the procurement of the transmission infrastructure and the government accounts will reflect a new debt. Once the funds are borrowed, the government can choose to either procure the transmission line itself or, in turn, lend the borrowed funds to the transmission utility which will procure the transmission infrastructure and repay the government from its revenue (diagram below). Even for the latter scenario, the government remains responsible for the entirety of the debt and will have to pay its lenders even if the transmission utility fails to repay the government.

On the African continent, the government is most likely to access financing for transmission infrastructure via concessional borrowing or ECA financing. The borrowed funds are used to procure and pay an EPC contractor to construct the specified transmission infrastructure. As explained in the funding chapter 2. Financing Structures and Capital Sources, MDBs and ECAs can lend to a government via the Ministry of Finance to fund capital expenditure costs. The Lake Turkana Transmission Line case study described below illustrates the use of concessional borrowing and ECA financing for the construction of a transmission line.

Case Study — The Loiyangalani–Suswa High Voltage Power Line (“Lake Turkana Transmission Line”)

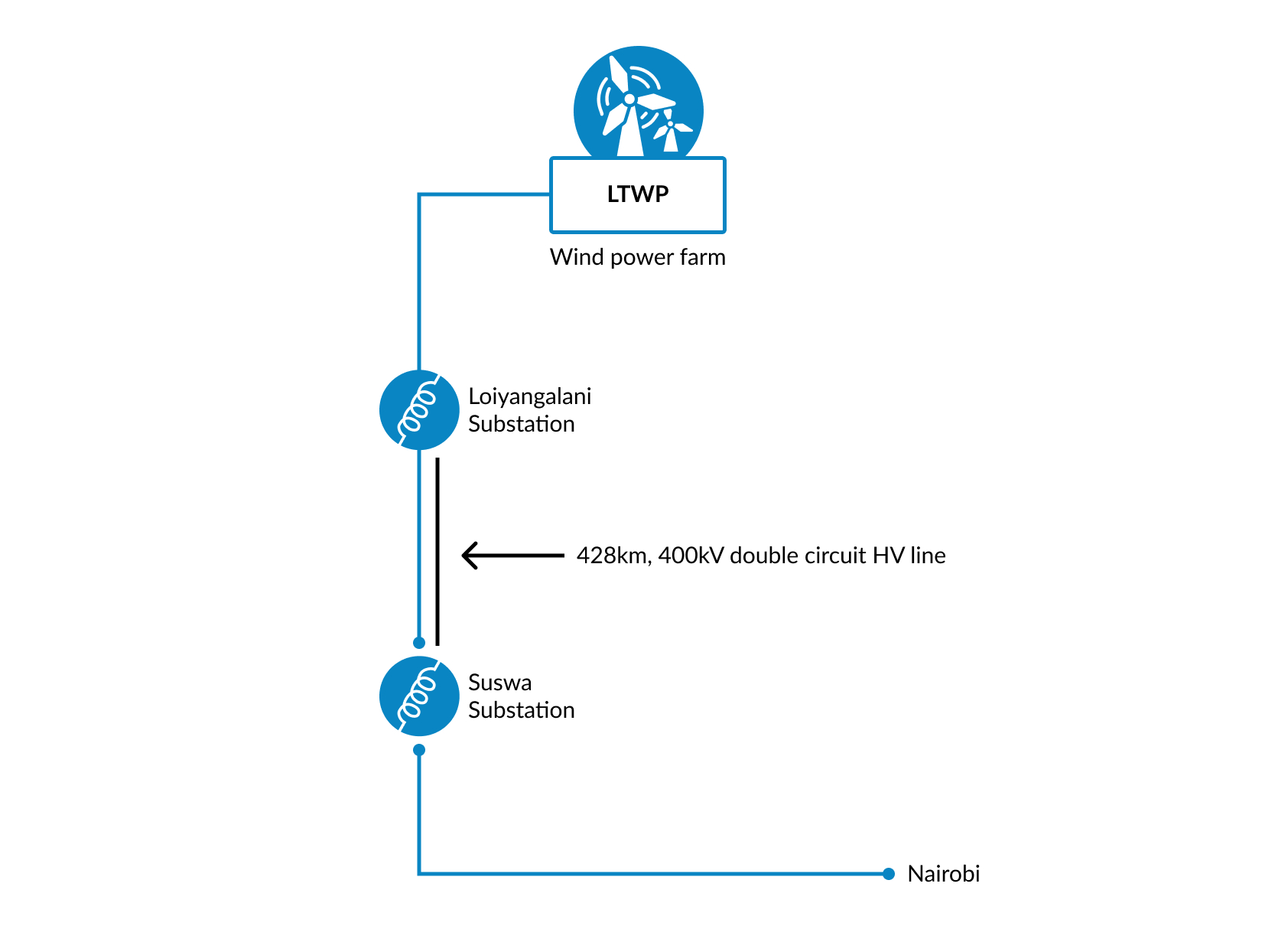

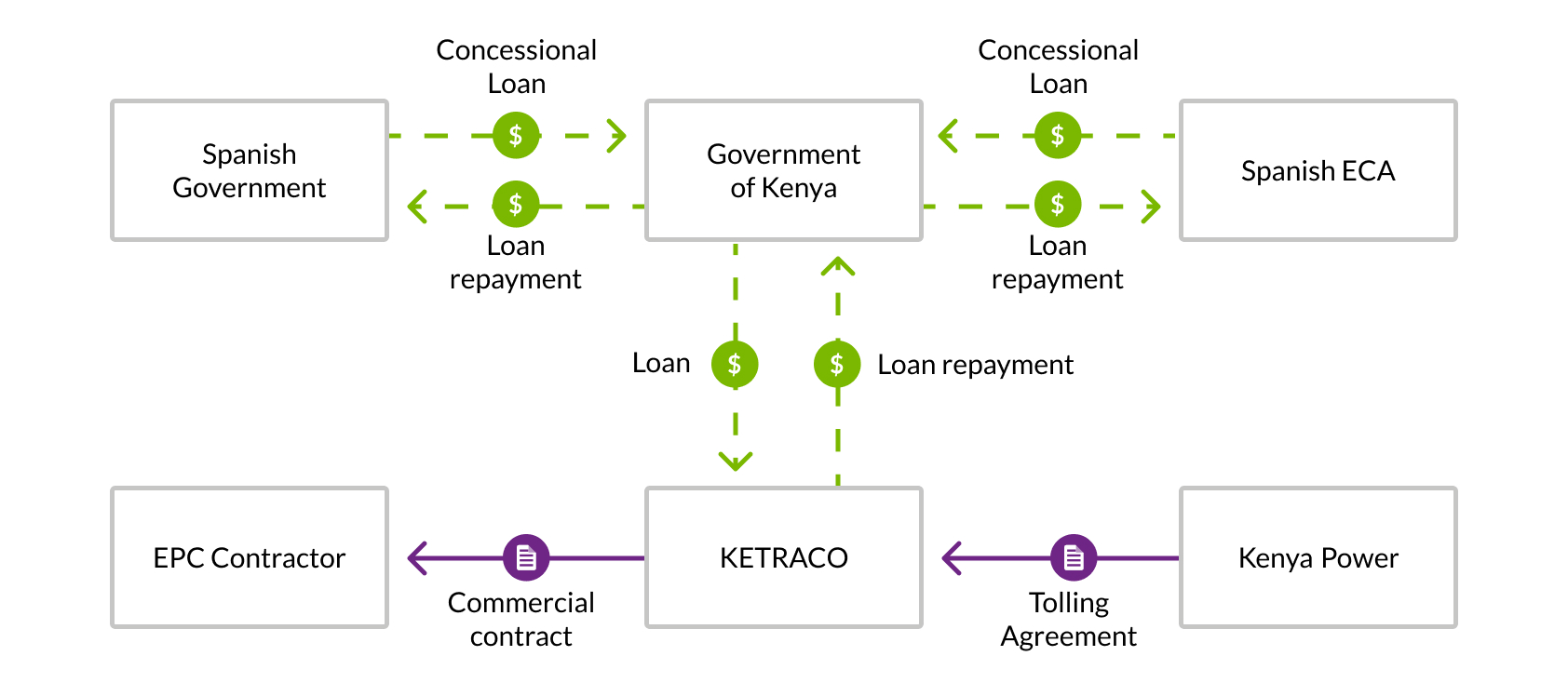

The Lake Turkana Transmission Line starts at the 310 MW Lake Turkana Wind Power plant in Marsabit County, Kenya, and runs south for approximately 428 km to the KETRACO substation in Suswa, Narok county, approximately 100 km west of Nairobi. In 2010, the Spanish government offered to finance the construction of the double circuit line. This included a concessional loan (for 30 years, with a low interest rate) of €55m and a commercial credit in an equal amount offered by the Spanish ECA (with commercial lending sitting behind it).

The Kenya Electricity Transmission Company (KETRACO), created in 2008, agreed to partly fund the line and substation by way of a tolling agreement with Kenya Power. With a large dedicated generation project attached, the potential for future generation projects alongside the transmission line corridor (an area with geothermal power potential) and the possibility for the line to interconnect with the Kenya-Ethiopia interconnector, the economic case for the project was clear.

Interface risk and cost overrun

The initial Spanish EPC contractor who was awarded the contract to construct the transmission line faced many implementation challenges, including a protracted wayleave and land acquisition process for which KETRACO was responsible, which delayed construction works. The initial Spanish EPC contractor subsequently filed for bankruptcy. The transmission line was eventually completed by a consortium of Chinese firms and officially commissioned in July 2019, behind schedule with a $96M cost over run ultimately financed from the government's balance sheet. The Lake Turkana Power Plant had already been commissioned in September 2018, earning deemed energy payments while waiting for the power plant’s connection to the grid to deliver energy to the wider Kenyan grid via the newly constructed line.

Given the Lake Turkana Wind Power project was an IPP and fully developed by the private sector, it raised an interesting discussion of “project on project” risk, with the two projects entirely interdependent but financed by separate means, and the former through commercial sources with the latter via sovereign borrowing. The risk allocation between the various stakeholders was heavily negotiated, with the Government of Kenya (GoK) bearing the responsibility for the timely delivery of the transmission line. The AfDB provided a €20 million PRG to backstop GoK’s completion risk on the transmission line, providing comfort to the Lake Turkana Wind Power lenders that deemed energy payment obligations would be met in the event the transmission line commissioning was delayed.

The Lake Turkana cost overruns highlight the magnitude of the interface risk for interdependent projects. For this reason, transmission lines are often wrapped in the financing and scope of a generation project. Further in this chapter, we discuss generation-linked transmission projects for which it was decided to finance and construct the transmission asset via the same project to significantly reduce the interface risk.

Government debt sustainability

The financing of transmission infrastructure from government borrowing is an attractive method of funding as it can produce favourable terms (e.g., low-interest rate, long repayment period, etc.) provided the government can afford the debt. This type of loan is not extended based on the transmission utility's ability to secure the necessary income to repay the loan but on the government’s fiscal ability to collect sufficient revenue to service and repay the debt. It, therefore, provides more flexibility and allows the government to rely on its full fiscal revenue for the development of the power sector.

Nonetheless, this method of funding requires careful management of the impact of the borrowing on the country’s debt sustainability efforts. Hence, the transmission project will have to compete with other projects as it will ultimately affect the country’s ability to borrow for other sectors of its economy. Moreover, the government will have to ensure that the transmission infrastructure will ultimately improve the viability of the sector as a series of uneconomical transmission financing can easily drain the government’s finances and have long-lasting repercussions on the overall economy. Furthermore, government balance sheet funding may be restricted by other international geopolitical factors as most government borrowing in SSA is provided by other governments, government agencies and MDBs.

State-owned utility borrowing

Countries with energy sectors that can independently recover their investment and operating costs have state-owned utilities that require minimal government subsidies or interventions to stay financially solvent. There are only a handful of state-owned power utilities in SSA that are sufficiently creditworthy to allow them to borrow from external sources. The repayment of the loan is not necessarily linked to the performance of the underlying asset that has been constructed but secured against other sources of income or revenue generated by the state-owned utility. The state-owned utility borrowing can be from ECAs and DFIs or the capital market.

An ECA and some DFIs can lend directly to the state-owned utility to fund the capital expenditure (CAPEX) requirements of a specified transmission infrastructure project, securing repayment against the utility’s balance sheet. Whereas the DFI will be agnostic on sourcing, as described above, the ECA will finance and disburse against invoices for a specified EPC scope of work which shows equipment and services from the ECA country.

Further, a creditworthy power utility responsible for transmission assets may choose to raise a corporate bond from capital markets for general-purpose borrowing, and then use a portion of those proceeds for investment in new, or the rehabilitation of existing, transmission infrastructure. An example of state-owned utility capital market borrowing is provided in the following case study.

Case Study — Caprivi Link InterConnector

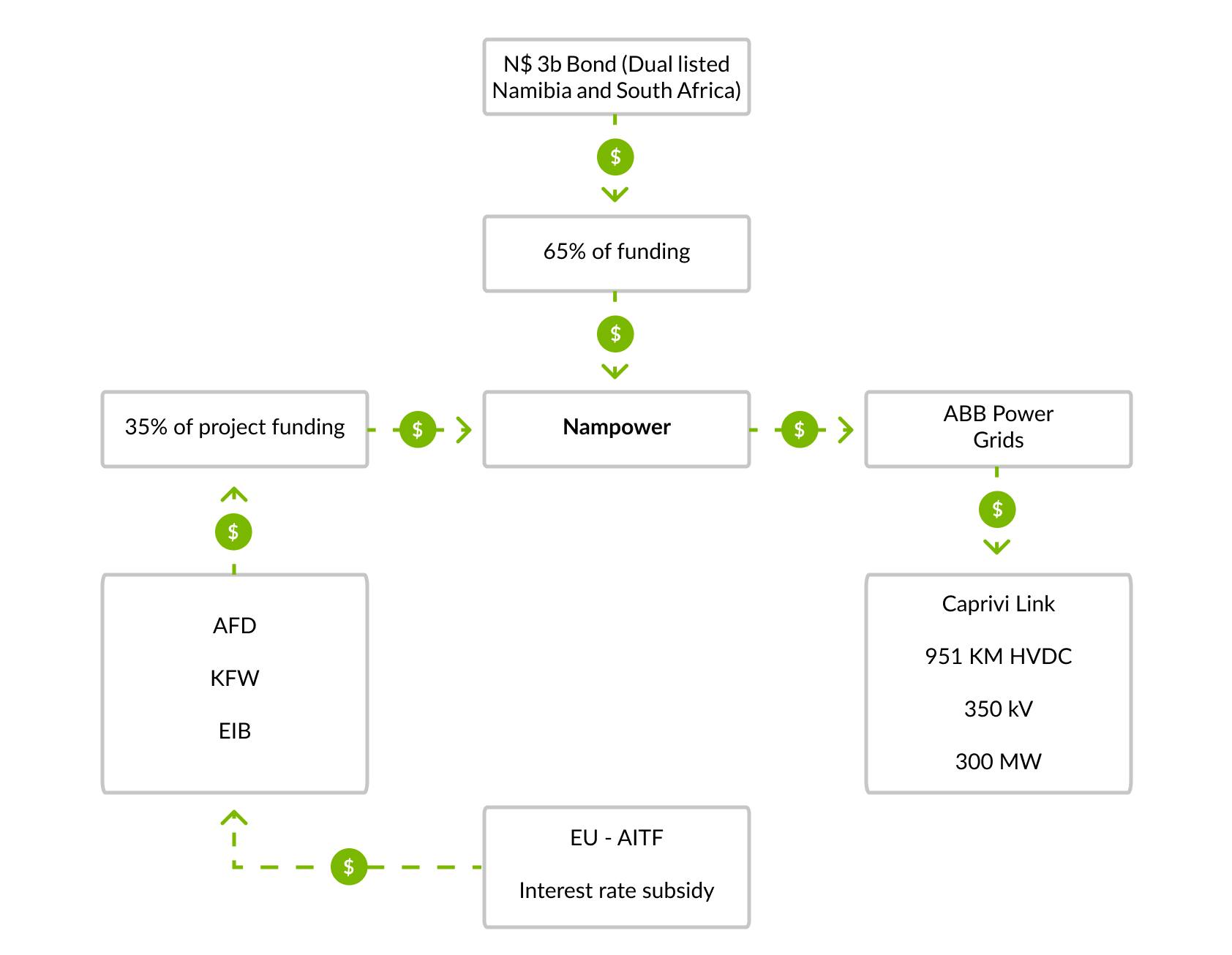

NamPower, Namibia’s national power utility, is responsible for generation, transmission and energy trading, reporting up to the Ministry of Mines and Energy. Its favourable and independent financial credit rating has allowed it to raise financing from the capital markets for its long-term projects.

In 2007, NamPower successfully dual-listed a $3B Namibian dollar-denominated long-term debt issue on both the Namibian and South African stock exchanges to fund the Caprivi Link Interconnector connecting Namibia to the Zambian and Zimbabwean electricity networks by 2009. Notable features at the time included a 300MW bipolar scheme, upgradeable to 600MW, and comprising a 951 km 350kV high voltage direct current (HVDC) bipolar line, along with numerous substations. This represented the first cross-border debt-raising transaction completed in Southern African capital markets, to finance a cross-border interconnection in line with the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) with the objective to interconnect all Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries.

Features of Public Sector-led Funding Structures

Ownership and control

Government-supported financing is the most common approach to financing transmission infrastructure projects in Africa. Government balance sheet financing supports infrastructure ownership and controls being retained by the government and/or the relevant transmission utility, thereby increasing the asset base of, and sources of revenue, for the country. In addition, the government or the transmission utility remains in full control of the technical designs, timelines and process in the development of the transmission infrastructure.

Where the transmission utility maintains ownership of the transmission infrastructure, it also bears the risk and responsibility for the proper management and maintenance of the infrastructure. This extends to:

- Proper planning and management of outages

- Regular and prudent maintenance

- Minimising losses due to theft or disrepair

- Swift reaction to repairs, defects, and emergencies

- Matters relating to security and insurance

This often results in significant reserves being required to meet the costs of such obligations.

Balance sheet impact

Public sector-led funding structures will affect the balance sheets of both the government and the utility. Such funding structures also affect the extent of the government’s debt sustainability. Hence, these structures require significant fiscal discipline.

Private Sector-led Funding Structure

Generation-linked transmission projects

There are examples of transmission infrastructure that is built by an IPP developer as part of a generation project. Generation power projects tend to be located as close as possible to fuel sources (river, coal mine, solar radiation, etc.). However, especially for renewable projects, the fuel sources are often far from existing grid connections and may require the construction of additional transmission infrastructure including substations. When procuring a new generation project, the government or the transmission utility may therefore decide that the transmission infrastructure is to be built by the IPP as part of the broader generation project and handed over to the government. Depending on the developer’s appetite and the size of the transmission line asset, the IPP might be interested to accept to take on the construction (and potentially financing) of a transmission line that will connect its project to the grid. Nonetheless, since the transmission line is transferred to the utility at some point in the project, the transmission line is ultimately will be government-owned.

This kind of model is used to reduce the connection risk in IPP projects. This ‘connection risk’ is the risk that the IPP or power plant is producing (or able to produce) electricity but cannot deliver it to end users because of a lack of connectivity to a transmission line. This could manifest itself in the construction phase of the power generation project where the delay in the construction and completion of the transmission infrastructure in turn delays the achievement of an anticipated commercial operations date under the power generation project.

This model allows the IPP to be in control of the interface risk between the two projects — generation and transmission. If this risk is not managed in this way, the typical remedy to the IPP is the inclusion of “deemed energy” payments under the power purchase agreement. These are payments calculated based on the loss of revenue from the energy that would have been delivered but for the transmission line unavailability event. Where generation is in the private sector but transmission is in the public sector, there is an increased financial risk on the government to pay these “deemed energy” payments (e.g., see above Case Study — Lake Turkana Transmission Line) to the extent the government or transmission utility does not manage or deliver the transmission infrastructure or make it available for the IPP to use.

The extra equity investment and debt funding necessary for the supplemental transmission work can either be repaid via a cash payment by the transmission utility when the transmission infrastructure is handed over or can be compensated through a higher generation tariff which reflects the additional fixed cost incurred to connect the power project to the national grid. The transmission asset will typically be handed over to the transmission utility at the commercial operation date, even if the cost of the construction is repaid to the IPP through the electricity tariff under the PPA.

Some considerations that arise when transmission infrastructure is built and captive to the benefit of one beneficiary (closed access for other usages) but which is ultimately handed to the transmission utility to maintain via public funds, is whether the transmission line still serves the greater public good. This may still be the case if the captive line provides reliable electricity to industrial users, who have wider economic benefits for a country.

Case Study — Self-build funding model in the South African IPP programmes

The South African government, through its energy ministry, has undertaken the competitive procurement of many independent power producer (IPP) programmes across various technologies since 2010. One of the most lauded of these programmes is the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP). Today REIPPPP is in its fifth round of procurement. As of the end of round 4 bidding, the South African power utility Eskom Holdings SOC Limited (Eskom) concluded PPAs for 92 renewable energy projects with a total capacity of 6327 MW. Grid connection and integration of the power generation facility to the national grid was a key feature of the REIPPPP.

Facing Eskom funding constraints and the short timelines required for grid connection, the REIPPPP was structured to allow bidders to elect to build the grid connection facilities on a "self-build" basis as part of their bid. The option was initially only made available for distribution facilities but in the second quarter of 2015, Eskom's transmission division introduced a self-build option to its customers, both electricity generators and consumers.

In this option, the customer can elect to design, procure, construct and commission the transmission assets. The customer undertakes the design, route selection and procuring of all authorisations, with consultation and the approval of Eskom, who ultimately ensures the transmission infrastructure aligns with existing grid technical specifications. After successful commissioning, the customer is obliged to transfer full ownership of the transmission assets and all environmental authorisations, wayleaves, approvals and permits to Eskom. Eskom states in its Transmission Development Plan published in January 2021 that the intention is to give customers greater control over risk factors affecting their network connection. However, it is important to note that transmission infrastructure expects that it is open access, meaning there could be the possibility of connecting other generation assets and other customers to the self-build transmission line after it is handed over to Eskom.

The self-build option has since also been expanded to allow customers to also build associated works (such as substations) that will be shared with other customers, based on an assessment by Eskom of the accompanying risks to the transmission system and other customers. Since this is purely a voluntary option, the option of Eskom constructing the generator or customer's network and paying a connection charge also remains available to bidders and customers alike.

What is important to note with this option is that the customer bears the risk and responsibility to finance the transmission infrastructure construction works, including the authorisations required and the wayleave acquisition (including compensation). These costs are recovered through the tariff over the term of the PPA, so IPPs need to consider these additional costs when bidding into the tender.

Due to the success of the self-build option, this approach has been adopted by the South African government in all subsequent IPP programmes.

Summary of Key Points

- Most existing funding methods of transmission infrastructure in Africa are public-sector led.

- They are akin to corporate finance structures as the financing is based on the ability of the government to raise financing and not on the viability of the cash flows from the transmission project specifically. Of these methods, government borrowing and ECA solutions (which also require a government guarantee) are by far the most common funding structures utilised.

- The most common private sector-led funding method used for transmission projects in SSA is the wrapping up of the construction and financing of the transmission project into a related IPP power generation project.

- Government-supported financing is the most common approach to financing transmission infrastructure projects in Africa. It can be an attractive method of funding as it can produce favourable terms (e.g., low-interest rate, long repayment period, etc.) if the government can afford the debt.

- There are examples of transmission infrastructure that are built by an IPP developer as part of a generation project. Depending on the developer’s appetite and the size of the transmission line asset, an IPP might be interested to take on the construction (and potentially financing) of a transmission line that will connect its project to the grid.