5

Independent Power Transmission (IPT) Projects

Introduction

This chapter will discuss the Independent Power Transmission (IPT) model, the scope of which involves the design, construction, and financing of a single transmission line or a set of transmission lines and/or associated transmission infrastructure such as substations. The IPT models described below assume transmission assets that are connected with the country’s wider electricity network rather than captive assets for the benefit of an industrial offtaker (which are discussed in chapter 7. Other Private Funding Structures). Although an IPT is typically used for the development of greenfield assets, we will also explore how the same concepts can be used for the refurbishment of existing transmission assets.

In emerging markets, IPTs are implemented under a long-term contract, generally between the state-owned transmission utility and a project company. The contract will typically define the economic payment model, and the roles and responsibilities for the new infrastructure, including ownership, construction, maintenance and financing responsibilities. These contracts can be structured as transmission service agreements (TSA) but may also take other forms such as lease or line concession agreements. In this chapter, the long-term contract will be referred to as a TSA although it might have another name in practice.

IPTs have a proven record in many countries across the world including Latin America and Asia. They are often described as a less disruptive intervention in the transmission sector than the other available private business models as they typically can be implemented with limited or no regulatory reform. The IPT model, therefore, has the potential to unlock many critical infrastructure projects in SSA and, if well structured, could help African transmission utilities quickly finance lines that have a direct and positive impact on their revenue.

IPT Business Models

There are a handful of different IPT business models which have successfully resulted in transmission infrastructure built, maintained and financed by private project companies. While very similar, in that the private party assumes construction and financing risk in all IPT models, they vary by degree of ownership and maintenance obligations which will normally change the terms of repayment and the risk allocation between the project company and the transmission utility. The return on investment expectations, as well as the cost of financing, will increase the more the project company bears risks that condition its repayment.

“Operations” — Line operation and maintenance or system operation

“Operations” in this chapter refer to specific maintenance activities required to ensure that a transmission line and other associated infrastructure are available to be used when specified. This is different from “System Operations'', which is carried out by the transmission utility/transmission system operator (TSO) on a whole network basis and involves system control and dispatch of generation facilities. Notwithstanding the IPT model used, system control and dispatch will be carried out by the transmission utility/TSO, not the project company. Hence, in this chapter, operations refer to “line operation & maintenance” only.

The TSA establishes the financial terms and period during which the project company is entitled to receive payment in exchange for ensuring the constructed transmission infrastructure is available to be operated by the transmission utility as specified. In most cases, the project company will not take demand risk (volume or price), or utilisation of transmission infrastructure risk, since the transmission utility will determine how, when, and by what means the grid is managed and electricity is dispatched. The simplest way of structuring TSA payments is as a fixed return on investment amortised over the term of the TSA, structured as a service charge with scheduled payment dates. This type of annuity (or unitary payment) very clearly defines the revenue stream by which investors and lenders can recover their respective capital injections, which should lower lenders’ cost of capital and investors’ return expectations. Also, when the transaction is structured appropriately, the annuity payment becomes the key criterion for selecting the winning bidder, assuming of course that competitive bidding is used.

The annuity payment will be sized to ensure the project company can recover expenses associated with capital expenditure, financing and operating and maintenance agreement (O&M) expenses related to constructing, financing and, if applicable, operating the transmission infrastructure. Depending on the IPT business model, there may be an element of payment variability associated with asset performance linked to O&M obligations. However, baseline payment will be sized to ensure ongoing debt servicing. Below are the most common IPT business models:

-

Build-Own-Operate (BOO): The TSA grants the project company

the right to build and maintain the transmission infrastructure

for an undefined period. Theoretically, the project company is not

obligated to transfer its ownership when the TSA terminates. This can

cause issues around ownership of the assets by the project company

but no clear legal basis for the revenue streams associated with it at

the end of the term. During the term of the TSA,

a portion of the annuity payment can be conditional on

the project company meeting technical performance specifications

or key performance indicators (KPIs), ensuring the transmission

infrastructure is available to be fully utilised when required.

- Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT): The TSA specifies that the project company has a responsibility to maintain and operate the transmission infrastructure for a period after the assets are constructed, before transferring ownership and O&M obligations back to the transmission utility. As with BOO, a portion of the annuity payment may be conditioned on the transmission infrastructure meeting predefined KPIs.

- Build-Own-Transfer (BOT): Once the assets are constructed, the TSA directs the project company to transfer the ownership of assets to the transmission utility upon project completion. O&M for the transmission infrastructure may fall outside of the project company’s responsibility and will most likely fall to the transmission utility. In this case, the annuity payment will be unconditional on the transmission assets’ performance, because the project company is not responsible for asset maintenance or operation.

In most IPT models that have been successfully implemented to date in Latin America and Asia, the private ownership of transmission-related assets is transferred to the transmission utility at the end of the TSA term.

BOOTs used extensively in Latin America

38 projects implemented in Brazil (220kV lines for a total of 50,000 km) and 18 projects in Peru (220kV and 500kV lines for a total of 7,560 km) were BOOT.

Enabling Environment

There are some countries in SSA that have the regulatory environment or experience with IPPs to be able to implement IPT business models within existing legislation. For countries with a track record in IPPs, IPTs could be considered a logical next step in using private capital to develop and expand their electricity networks. Many of the same government stakeholders who are familiar with the process and requirements of an IPP are likely to have the capacity and relevant experience to enable IPTs, especially when generation and transmission are bundled under the same utility.

In many countries, a transmission licence will need to be granted to the project company, either by a regulator or other relevant authority. There may also be a legal prohibition on private companies owning and operating transmission infrastructure (e.g., due to concerns about the natural monopoly characteristic of transmission infrastructure). If there are legal prohibitions, then there may be ways to structure around this as described in the section below (Ownership of transmission assets). If this is not possible, then an IPT business model can only be implemented if the regulatory structure is amended to allow the granting of a licence or appropriate authorisations by the regulator or relevant authority.

A regulator will typically have a role in approving (and likely licencing) the project company to implement a specified IPT business model. Thereafter, the regulator is likely to be responsible for monitoring compliance with licence conditions, which could include identified KPIs under the TSA during the O&M phase. When the TSA includes a simplified payment model, which eliminates demand risk, the regulator will typically wish to understand and approve the payment model. Before a TSA is being agreed to, the regulator needs to understand the cost and benefit to the sector but will not need to review complex tariff methodologies periodically during the TSA as required with power generation projects.

How It Works

Project phases

There are three key phases of an IPT project:

- Project development

- Construction and

- Operations

Project development phase

See chapter 9. Planning and Project Preparation for a description of the planning process of transmission projects. Project selection is critical in determining which transmission infrastructure is suitable for an IPT. Some of the key criteria to examine include:

-

The commercial case for the project

The economics of the relevant project will have to be analysed based on the available data on the sector’s financial viability and growth prospects, and a set of assumptions. Projects that deliver the following efficiencies are well suited for an IPT business model: (i) can be delivered faster with lower O&M costs by the private sector, and (ii) likely to improve the sector’s cash flows by increasing the network’s availability (e.g., by connecting new end users to power supply, thereby meeting unserved demand). These types of projects are generally identified during the power system planning phase.

-

The suitability of alternative funding sources

An analysis of whether there are other funds in the budget at the national, ministerial, or utility level for the financing of the infrastructure should be completed. The government should also assess whether there are donor funds readily available to procure the project without it being an IPT — if this is the case, some efficiencies from the private sector’s ability to maintain and operate the asset at a lower cost may be lost. If some alternative funding sources are identified, the government should then decide whether the transmission infrastructure is the best use of these funds.

-

The project size

An IPT is unlikely to be a suitable solution for smaller projects. Typically, for projects less than US$50 million, given the expense required for project preparation and execution, an IPT may not be the most suitable method of financing. It should be noted, however, that a series of smaller projects can be aggregated into a portfolio and executed as part of a single IPT investment.

-

If there are any particular

challenges associated with a particular project

An assessment of the overall legal and regulatory regime will be key to identify any particular challenges with an identified project. Environment and social risks should also be considered early to avoid obstacles that might stifle the financing efforts at a later stage (e.g., the construction of a transmission line through a protected natural reserve). This is not to say that easy projects should be implemented through the IPT model, but it would be wise that the first IPT project does not have added complications, as implementing a privately financed transmission project is challenging enough in a country with no relevant experience.

The host country can decide to allocate a project to a developer at an early stage in the project’s development or to undertake a certain level of preparatory work first. Allowing the developer to take responsibility for early-stage preparation provides more flexibility and may result in more innovation and cost savings. It also relieves the government from raising funds for project preparation and requires less capacity and government resources, although external funding may be available for conducting feasibility studies by the government or by the private sector. On the negative side, the developer needs to be selected before the design and investment requirements are finalised.

Countries can also choose to carry out a certain level of preparatory work centrally before conducting an auction or tender process to attract a greater level of investor interest and procure the most cost-effective construction solution and lowest cost of financing. While effective, this approach requires more resources initially to manage the project preparation phase until the developer is selected. Further detail on choosing between these approaches can be found in the Understanding Power Project Procurement handbook.

Regardless of who will be responsible for each activity, the following workstreams need to be completed during the preparation stage:

- Comprehensive feasibility study. A feasibility study will be required, which reaffirms the need for the project, evaluates the alternative design options and recommends a specific scope based on an economic analysis of the project and its alternatives. The recommended scope along with the grid code (if it exists) would form the basis for the design specifications.

- Environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA). Environmental and social issues need to be identified as early as possible in the project development phase. An ESIA will be required; they are usually conducted by third-party environmental consultants. Even a preliminary ESIA could identify major environmental and social issues which may have a substantial impact on the project (affecting its design or routing or even stopping the project). Early consultations with all the key stakeholders are essential, including those concerning the potential resettlement of peoples in areas along the transmission route. Requirements by lending institutions may be relevant and need to be taken into account.

- Development of an EPC procurement strategy. How the project will ultimately be built and delivered will be dependent on the strategy of the transmission utility and relevant ministry. Assuming an IPT route is chosen, the IPT themselves will have to choose how to procure the project, i.e. they will typically run a process to choose an EPC contractor (or separate suppliers of equipment and a contractor for civil works). This can be a complex process due to issues of risk transfer and mitigation between the transmission utility, project company, and construction contractors.

- Permitting and licensing. There may be several permits and licenses that need to be obtained, and it is important to lay out a plan as early as possible. Such permits and licenses may include the following: land acquisition/lease, construction permits (including access to the site), environmental permits, grid connection agreements, operating permits, etc. If the country has a grid code, it should be taken into account in both the design of the assets and the required licenses/permits.

- Developing a financing plan. This will be an early stage consideration and those developing the project will keep improving it as the project moves forward, more information becomes available, and risks are affected. Cost of financing and key terms required by financiers will impact project cost and delivery and this needs to be worked on iteratively with the other development workstreams. See chapter 2. Financing Structures and Capital Sources for further details.

The development phase will end when the project reaches “financial close,” i.e. when all conditions precedent to the disbursement of the debt required for the project have been met, and monies disbursed.

Construction phase

After a financial closure has been achieved, construction will begin. The project company will typically be responsible for managing the project activities required to complete the infrastructure, although in some instances there may be a third party acting as construction manager. Even in the case of a single contractor (EPC), an owner’s engineer will typically be retained to supervise all aspects of the project and advise the project developer/owner. Some financial institutions may employ their own engineers and legal advisors to monitor construction, in particular the environmental and social aspects. Lenders will typically disburse their loans to fund the construction of the assets during this phase, although in some cases the equity investor in the project company may decide to finance the construction phase and refinance once the asset is built and delivered.

Operations phase

Generally speaking in IPT models, the control and dispatch of power will be the responsibility of the transmission utility acting as TSO, given the interface with the wider network. It is possible, but rare, for the private sector project company to take operational control of a section of the transmission network. Maintenance of the asset, which may include some localised operational activities, may be the responsibility of the project company. The project company may decide to have its own staff or hire a contractor to undertake this maintenance. In some cases, maintenance will be the responsibility of the transmission utility, either under the terms of the TSA or because the project company contracts back to the transmission utility under a maintenance agreement. The role of the project company in this respect has an impact on investor risk and is likely to determine the most suitable payment model that is agreed between the project company and the transmission utility (or an alternative offtaker). The decision as to which party is responsible for the maintenance and/or localised operations is a function of the risk analysis and how the project fits into the overall system strategy of the government.

Stakeholders

The roles of each relevant sector participant concerning an IPT are set out in the table below.

|

Sector Participant |

Role |

|---|---|

|

The project company will have at least one shareholder/equity sponsor. In the case where projects are allocated earlier in the process, the owner of the project company will probably also develop the project. The developer will then either fund the project company with sufficient equity to capitalise it in the long term at a financial close or it will bring in a new shareholder. As with the IPP sector, developers usually carry out work and fund early-stage activities “on risk” in consideration for earning development fees, which are typically paid at financial close. Among the other project development activities undertaken by the developer/equity sponsor, it will take responsibility for arranging debt finance for the project company. During the lifetime of the IPT investment, the developer/equity sponsor will manage the project company and be the key point of interface between the project company and the stakeholders. |

|

Lenders will finance the project company with loans. They will typically be mandated during the development phase to review the contracts developed by the developer/equity investor and test their “bankability” ahead of financial close (see below). At the financial close the lenders will fund the project and their loans will be drawn down to fund construction. IPT lenders include MDBs, bilateral DFIs, ECAs, and donor agencies. To provide long-term lending, international commercial lenders will likely only be able to participate with some kind of political risk or credit insurance from an ECA or DFI. Some local funding may be available as part of an overall funding package. |

|

The “offtaker” is the organisation responsible for paying the IPT under the Transmission Services Agreement. In most cases, this will be the transmission utility, but it could be a different organisation in some countries, such as a distribution company or another government entity. |

|

The transmission utility’s role in the sector is unlikely to change as a result of an IPT project. In most cases, the transmission utility will continue to be responsible for all transmission operations in the host country and it will control dispatch and system operations. Existing infrastructure owned by the transmission utility will interface with the IPT’s infrastructure. The terms of many IPT projects will involve the transfer of the assets of the IPT project company to the transmission utility at the end of the term of the TSA. |

|

The government’s role in an IPT project is typically to assume certain state risks to protect the project company from risks it is not best placed to manage. The agreement between the government and the project company may be reflected in the Government Service/Support Agreement (GSA), which needs to be agreed upon and signed by both parties. The government here could be one or more ministries (usually the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Energy, or their equivalents) and may also include a Ministry of Land. A PPP Unit or Presidential Delivery Unit may also be a relevant governmental stakeholder. The level of support provided by the government in this respect will have an impact on the availability and pricing of debt and equity finance available for the IPT project. See further discussions in chapters 2. Financing Structures and Capital Sources and 11. Common Risks for further analysis on the range of government support available during both construction and operations phases. |

Contractual Structure

Risk Allocation Matrix

The risk matrix below summarises how key risks might be allocated to different stakeholders within a TSA. For a more detailed discussion and commentary on the individual risks, especially as they pertain to private investment in transmission infrastructure, please see chapter 11. Common Risks.

Please note that the table below is indicative and not meant to be exhaustive. The precise risk allocation between the parties on any particular transaction may be different to what is identified below as typical. Risk allocation is always subject to the fact pattern existing in relation to a particular transaction, investor appetite, and what risks a government is prepared and able to take on with respect to a particular transaction.

|

Risk |

Stakeholder bearing risk |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Govt/ Transmission utility |

IPT project company |

|

|

Financial risk |

|

|

|

Demand risk |

|

|

|

Credit risk |

|

|

|

Inflation |

|

|

|

Interest rates |

|

|

|

Foreign exchange rates |

|

|

|

Buy-out payment |

|

|

|

Land |

||

|

Pre-existing environmental conditions |

|

|

|

Pre-existing conditions in the title |

|

|

|

Land acquisition |

|

|

|

Technical risk |

||

|

Construction and commissioning of assets |

|

|

|

Scope changes before or during construction |

|

|

|

Interface between lines, substations, and generation facilities |

|

|

|

Technical risks related to the adoption of new technologies |

|

|

|

Operation, maintenance, technical performance |

|

|

|

KPIs, service levels |

|

|

|

Accidents, damage, theft |

|

|

|

Social and environmental risk |

||

|

Social and environmental impacts |

|

|

|

Occupational health and safety |

|

|

|

Resettlement |

|

|

|

Non-political force majeure events |

|

|

|

Political and Regulatory Risks |

||

|

Initial issuance of licenses, permits |

|

|

|

Renewals, modifications |

|

|

|

Changes in law |

|

|

|

Changes in tax |

|

|

|

Political force majeure events |

|

|

|

Disputes |

||

|

Resolution of disputes arising under contracts |

|

|

Financing Structure

One of the main advantages that IPT business models bring is the ability for transmission utilities or host governments to expand transmission infrastructure using off-balance-sheet financing, via third-party investment and financing, freeing up financial resources for other purposes.

Security Arrangements

It is important to note that while asset ownership may lie with the project company for the duration of the TSA term, in practice, the key form of security relied upon by project lenders will be the revenue stream set out within the TSA. As indicated above, while a project company may be entitled to own the transmission infrastructure which it constructs permanently, the regulatory licensing regime or the TSA itself may dictate that the ownership of transmission infrastructure be transferred to the transmission utility at the end of the TSA term.

The TSA term is purposely defined for a long period (15 years plus) to spread the cost of long term transmission assets across many years and minimise the short term impact of servicing these payments on tariff structures. Payments are likely to follow a regular schedule over the term of the TSA.

Payment risk

As discussed earlier, simplified payment structures based on the availability and performance of the transmission infrastructure strip away demand risk based on utilisation (volume or end-user fees). This has the benefit of clearly defining a predictable revenue stream which represents a lower risk for investors and therefore attracts a lower cost of capital. Any variability to the revenue stream introduced via KPI metrics based on a split of risk allocation between the project company and the transmission utility (e.g., for commissioning or O&M responsibilities) may impact revenue risk but has the advantage of ensuring service quality, which should improve the operating performance and “availability” of the transmission infrastructure.

Payment risk mitigation

Whether additional credit support from a host government is required will be a function of the credit of the entity responsible for making scheduled payments. To the extent the paying entity, or offtaker, has a healthy balance sheet or the payment obligation is irrevocable and can be insured, there may be no need for a full sovereign guarantee to backstop ongoing or termination support. Minimising any sovereign contingent liability has the benefit of freeing up fiscal space.

If there are concerns about the offtaker’s ability to make timely scheduled payments, the following can be pursued to provide liquidity support:

- government Support Arrangements including termination payments in the event of non-payment under a TSA;

- sector collection accounts that give a degree of priority in payment waterfalls to investors;

- establishing a bank account or a letter of credit structure that maintains 6-month payment reserves; and

- non-sovereign credit enhancement products. These are described in more detail in chapter 2. Financing Structures and Capital Sources.

Advantages of IPT models

Although ECA support (typically for an EPC contractor) offers a host government an off-balance sheet funding solution, the ECA still requires an implicit guarantee by requiring the MoF to be a borrower for their financing facility which can put pressure on the country’s debt capacity. In addition, the ECA requirement that the borrower provides a 15% contribution means there is still some amount of cash outlay expected from public resources, usually in the form of a down payment. While there could be alternative ways to finance the 15% contribution, this will take additional time and resources to structure, which can result in other inefficiencies.

While IPT financing may be more expensive than concessional loans or ECA financing benefitting from an implicit sovereign guarantee, it can attract a more diverse set of lenders and result in a lower cost for the project. As highlighted in the risk allocation matrix above, many types of lenders can provide cost-competitive financing to support IPT business models. As outlined in the contract structure diagram in Figure 5.1, the borrower will be the project company that enters into distinct construction and TSA contracts, and if applicable, an O&M services agreement. Depending on the amount of financing to be raised, the lender(s) can include MDBs, bilateral DFIs and ECAs who can provide long-term loans. Commercial lenders may be able to provide longer tenor loans with additional political and/or credit risk insurance from an ECA or MDB.

Other Considerations

Aside from mitigating offtaker payment risk, there are a couple of other issues worth considering when choosing to implement IPTs which deserve special mention: land acquisition/right-of-way issues, and transmission infrastructure ownership.

Land acquisition

Land acquisition is dealt with in chapter 10. Land Acquisition. To implement an IPT, the party that is best placed to manage this process is best decided on a case-by-case basis. However, the experience from around the world suggests that land acquisition/right-of-way risk, in most cases, is best handled by the government or a public sector entity. Even countries with very well-functioning power markets and numerous private transmission projects already being implemented (such as Brazil) have the government responsible for land acquisition.

In addition to ownership and local opposition, funding for acquiring the land and compensating the various stakeholders may be an obstacle too. Investors can play an important role, working with the government, to ensure that adequate funding is available and the compensation is fair and is done promptly. Land issues should be resolved before the agreement with the private investor is concluded.

Ownership of transmission

This section has focused on implementing IPT business models for greenfield transmission infrastructure assets to raise financing that is off the government’s balance sheet. As outlined when defining IPT business models, the assumption is that the private sector will obtain a licence to own the transmission infrastructure for some time, after which the infrastructure is transferred to the transmission utility as set out in the TSA. This could be for a period of e.g. 20 or 30 years and is sized to allow the private sector developer to make a return on its investment.

This follows the example of how PPP business models have been applied to raise third-party financing to build other types of infrastructure, especially power generation assets. It is rooted in the philosophy that ownership of the asset runs concurrently with the project company’s right and ability to operate the relevant asset. It is typically also a lender requirement that the project company owns the asset for the long term, so that in a scenario where the project company has not been able to repay the debt it has incurred (e.g., because the transmission utility has failed to make payments to the IPT), lenders can recover their costs by selling the assets over which they have taken security. Lenders will always take some form of security (collateral) over the project company’s rights, title and interests — and having security over assets ensures that lenders have recourse to something of value, which they can sell (or at least have the right to do so) if things have gone wrong and the project is in default. Those rights are tied to the private ownership of the assets themselves.

In transmission infrastructure projects, where the operation of the relevant asset (e.g., the operation of a transmission line) may rest with the government utility, the same logic of ownership may not necessarily apply. In addition, unlike, for example, a generation asset such as a power plant, dismantling hundreds of kilometres of transmission infrastructure in a host country to sell to other parties (i.e., taking the ultimate step to enforce security to repay the debt) is likely to be less practical than for other types of assets. The analysis on ownership will therefore depend on the relevant transmission assets in question, who is operating it; and lender expectations. Security over revenue accounts associated with the predictable revenue stream and any credit-enhanced liquidity solutions and other contractual arrangements are arguably where lenders should focus their attention when structuring bankable solutions, rather than who owns the asset.

If this principle is accepted, there is room to argue that IPT business models do not need to rely on private ownership, in which case the refurbishment of existing transmission lines owned by the transmission utility could raise third-party financing along the same fundamentals outlined in previous sections of this chapter.

Case study — IPT: Peru

Peru is a country of 31 million people. Peak electricity demand is around 6200 MW and electricity production is nearly 50/50 hydro and thermal, even though renewables are increasing. 85% of the installed capacity is linked to the national power grid (SEIN) and 15% is in isolated systems. According to the World Bank in 2018, the length of the transmission lines was approximately 22,600 km. The majority of the demand is along the coast, as shown in Figure 5.2. Strengthening of the transmission capacity was a priority in the late 1990s and early 2000s when many transmission projects were implemented.

Reforms in the sector started in 1992, resulting in full deregulation and substantial privatisation. Eventually, there were 70 power generators, of which 65 rivately supplied 63% of the total energy. There are 14 transmission companies, all private, and 23 distribution companies of which 13 are private with 67% market share. Regulation of the power sector was well-designed and very effective in supporting a well-functioning power market.

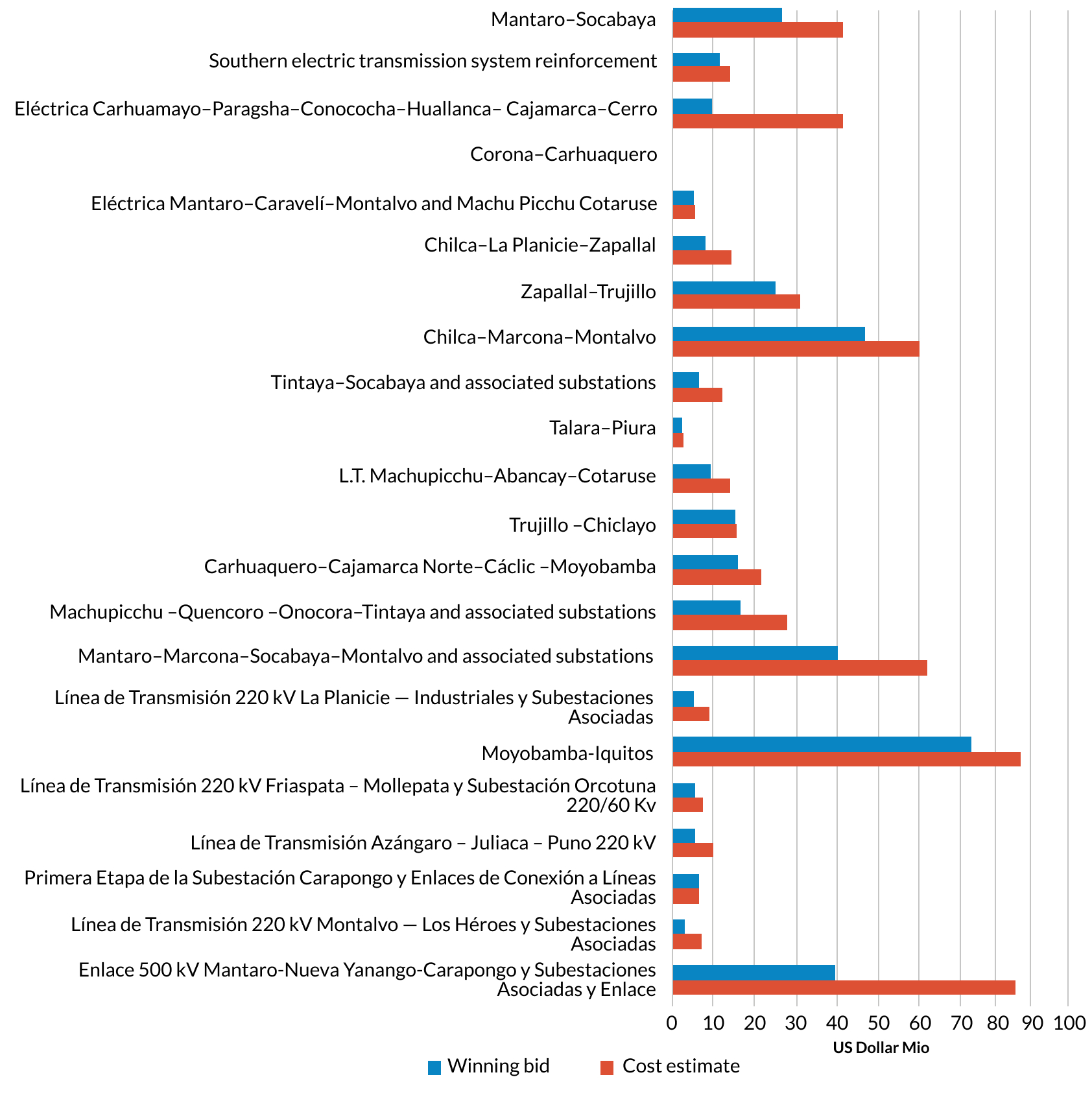

Procurement of privately financed transmission projects started in 1998. The PPP process provided the framework for procuring transmission projects. Early on, it was decided that a BOOT model would be used and private investors would be selected through a competitive process. A well-balanced risk allocation matrix (among the investor, offtaker and government) provided the basis for de-risking these projects, leading to very competitive tariffs and substantial savings, as shown in Figure 5.3. The basis for bidding was an annuity, independent of demand and utilisation of the assets.

Eighteen tenders have now been completed leading to the implementation of a total of 7,560 km transmission lines (220kV and 500kV) and a total budget of $2.6 billion. All these projects were based on a BOOT model and were 30-year contracts.

An important conclusion that can be drawn from the Peruvian experience is that privately financed projects have been implemented at a fraction of the expected cost. The experience in other countries (e.g., Brazil and India) were similar. As an illustration of this, Figure 5.3 below shows that the winning bids in Peru provide significant savings to the electricity sector versus projected costs (an average of 36% lower).

A case needs to be made on a project-by-project basis as to whether the benefits of an IPT in terms of availability of funding, flexibility of funding, and risk transfer to the private sector, mean that this is the most appropriate solution. The risks that the project company agrees to take will, to a large extent, determine the returns required by investors. An IPT will not always be the best solution and most countries will likely have a long list of projects that are more suitably funded with support from public funding sources.

However, experience in many countries demonstrates that when well structured and applied to the most appropriate projects, IPTs can create substantial value for the sector, improve the quality of power and enhance energy access. They can lead to efficiencies and lower costs for tariff payers.

Strategically, a host country’s decision to involve the private sector in the transmission subsector is a sensible way to improve power sector efficiency and reduce power supply costs. However, a necessary supplement to privately financed transmission should be a roadmap to power sector financial sustainability. IPTs can play an important role in making power sectors more efficient by unlocking critical projects that increase network ability to deliver power to areas of unmet demand and therefore increase sector cash flows. If correctly structured, they can also bring very material efficiencies, as illustrated by the experience of Peru described above.

Summary of Key Points

- Independent power transmission projects (IPTs) involve the design, construction, and financing of a single transmission line or a set of transmission lines and associated infrastructure such as substations.

- IPTs are implemented under a long-term contract, generally between the state-owned transmission utility and a project company. The contract will typically define the economic payment model, and the roles and responsibilities concerning the new infrastructure, including ownership, construction, maintenance and financing responsibilities. These contracts can be structured as transmission service agreements (TSA) but may also take other forms, such as lease or line concession agreements.

- Thousands of kilometres of IPTs have been developed in Latin America, India, and elsewhere. An important conclusion that can be drawn from the experiences of Brazil, Peru, India, and other countries is that IPTs are often implemented at a fraction of the anticipated cost. In Peru, for example, IPTs cost 36% less than expected on average.