6

Whole-of-grid Concessions

Introduction

Governments will consider a whole-of-grid concession when there is the expectation that a concessionaire can (1) better maintain and operate the existing transmission network to improve the overall availability and ultimately utilisation of transmission infrastructure and (2) invest in extending/upgrading the network to improve reliability and access to the power supply.

A whole-of-grid concession extends the right to develop, construct, operate, and maintain transmission infrastructure (the “concession”) to a private sector concessionaire, who in turn receives remuneration for the concession period. A concession can be a grant of rights or property, depending on the jurisdiction. Transmission assets are either leased or sold by a government or transmission utility to a private sector concessionaire to take over the role of the transmission utility via a concession agreement, a lease and assignment agreement, or a similar agreement.

Regardless of the contract form, the concessionaire may have to pay an upfront investment for the rights to maintain and operate the transmission infrastructure, although this is not always the case. The concessionaire would typically be compensated via payments it collects from its customers (generators, distribution companies, or industrial consumers that are directly connected to the transmission system).

The upfront payment owed by the concessionaire, and the form of this payment, is covered in further detail later in the chapter. The amount the concessionaire is required to earn in a year to cover its costs and earn a return on its investments (the annual revenue requirement) is calculated using performance-based rate making or cost of service regulation. In either ratemaking method, the revenue requirement is based on the regulated asset base (RAB) or rate base — a measure of the value of the assets which are used to perform a regulated service. In a whole-of-grid concession, the RAB would include all transmission infrastructure the concessionaire is expected to maintain, operate or expand to deliver services to a defined customer base (e.g., generators, bulk distributors, large industrial customers, etc.) in a defined geographic area. In exchange for delivering these services, the concessionaire earns and collects fees directly from those customers.

In principle, this methodology assumes that customers are paying a cost-reflective tariff that will ensure full recovery of the concessionaire’s investment in transmission assets, reducing the investor’s risk of investing in capital-intensive projects. If regulated tariffs are below what the concessionaire requires to recover its costs, then the transmission utility or other government entity will be required to compensate the concessionaire some other way. This is covered in greater detail later in the chapter.

Concession Models

There are two main ways a whole-of-grid concession may be structured:

- concession for the whole existing transmission network; and

- concession of a portion of an existing transmission network, which can be limited to a territorial area or identified transmission lines and related infrastructure.

The concessionaire, via a project company, is typically responsible for:

- the operation and maintenance of the transmission infrastructure;

- refurbishments, restoration and repairs to existing transmission assets;

- construction of new transmission infrastructure, upgrades, and expansions within the concession area;

- all investments required for the stable and efficient operation of the transmission infrastructure; and

- operational control of the transmission network within the concession area.

The rights conferred to the concessionaire must allow it to exert sufficient and unfettered control to manage its transmission network responsibilities without government or transmission utility interference. The government’s role is limited to an oversight role — i.e., an independent regulator that oversees tariff methodology and a planning role — set out in the concession itself. This “concession” right, depending on the jurisdiction (and asset), could be a grant of rights, land or property, or a combination of all three. However, title to the relevant land and properties may not always pass to the concessionaire as a result of the concession. What is more important is that the concessionaire retains the rights to control, maintain and operate the relevant asset — in this case, the entire national grid — and that these rights are granted in a manner that is legally valid, binding and enforceable (including with parliamentary or cabinet-level approval, where necessary).

In all cases, the transmission assets are transferred back to the transmission utility at the end of the concession.

Enabling environment

Whole-of-grid concessions are suitable in jurisdictions that have an independent electricity regulator and have a regulatory framework that allows for third parties (such as a concessionaire) to hold a transmission licence that permits them to construct, operate and maintain transmission infrastructure. It is also important that the legislative framework permits private sector parties to own or operate strategic transmission assets. Changes to legislative and regulatory frameworks to permit whole-of-grid concessions where the existing regulatory regime does not permit investors to be concessionaires can be a complex, expensive, and time-consuming undertaking.

The allocation of risks in a whole-of-grid concession also plays a significant role in determining the success or failure of efforts to structure and award a concession. This is discussed in further detail later in the chapter.

Tariff considerations

Considering the ongoing investment required in the operation and maintenance of transmission infrastructure, it is not practical to establish a tariff from the outset that the concessionaire may charge customers for use of the transmission service for the entire term of the concession. To avoid renegotiating, restructuring, or early termination of a concession due to an insufficient or inadequate tariff, the tariff methodology the regulator intends to use should be clearly articulated in a set of tariff guidelines or the concession agreement. The two most common forms of regulation on which tariff methodologies are based are the cost-of-service approach and performance-based regulation. While these will not be covered in detail in this book, each has its advantages and disadvantages which need to be carefully considered.

The important principle is that the concessionaire’s annual revenue requirement should be sufficient to allow for a return on the RAB equal to the amount of the RAB times the weighted average cost of capital, operating and maintenance costs, taxes, and depreciation of existing assets.

The soundness and certainty of the RAB valuation and associated tariff methodology are critical to the success of implementing a whole-of-grid concession, given that the tariffs charged to customers for their use of the transmission infrastructure are the main source of revenue (and in some instances the only source of revenue) to the concessionaire.

A concessionaire’s revenue shortfall may sometimes be as a result of its failure to meet certain KPI set by the regulator. In this case, the government or the transmission utility would not be required to cover such a shortfall. However, if the shortfall is a result of the regulator’s failure to apply appropriate tariff guidelines, the government or the transmission utility will need to find an alternative way to compensate the concessionaire or face a potential termination of the concession. The compensation may take the form of a one-time payment or an ongoing subsidy to the concessionaire.

If there is a material unfavourable future change in the tariff methodology that does not adhere to the principles of full cost recovery plus a return on investment, this would be detrimental to the financial viability of the concessionaire. The government support agreement (discussed in further detail below) would typically address this risk.

In countries that do not have an established independent regulator, economic regulation can still be achieved through a government support agreement or concession agreement which includes an annexe that describes a regulatory methodology. The government support agreement (between the host country and the concessionaire) or the concession agreement (between the transmission utility and the concessionaire) will then govern the relationship between the asset owner and the service provider, and the relevant government counterparty will be responsible for monitoring the performance of the operator and for applying the regulatory methodology following the terms of the contract. This system is known as “Regulation by Contract.”

Case Study — Transmission Concession: Philippines

Source: Private Sector Participation in Electricity Transmission and Distribution/ Experiences from Brazil, Peru, The Philippines, and Turkey (World Bank, 2015), pages 6-9.

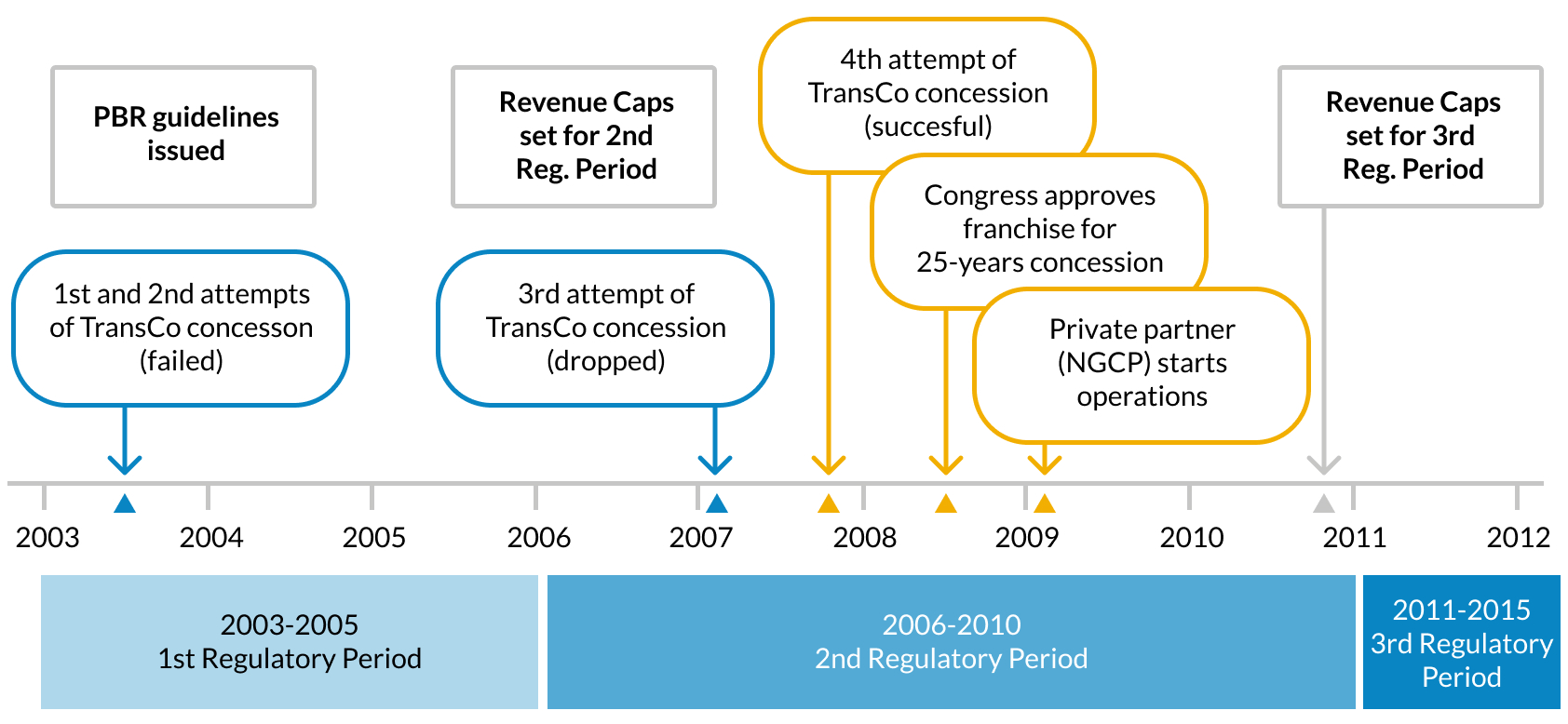

The Philippines is an example of a long-term (25-year) concession for existing transmission assets. The main goal was to raise capital for the sector and the Treasury. This goal was eventually satisfied even though it took longer than initially expected; privatisation of the transmission system attracted close to $4.2 billion in a concession deal that closed in 2007.

Initially (2001), the regulatory framework was established under a comprehensive restructuring and privatisation programme, known as the Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA). At the same time, the energy regulatory commission (ERC) was created. Performance-based regulation (PBR) formed the basic framework and a specific methodology for regulating the revenues of the transmission company was developed. A "revenue cap" approach was adopted for the transmission company.

While the essential regulatory elements were in place since 2003, it took a few years for the ERC to improve the rate-making methodology and impose the necessary discipline for setting the specific revenue cap levels. As a result, there were two unsuccessful attempts before the third successful one in December 2007. Bidders were very interested to invest in the Philippines mainly because of the following three factors: (1) there was promising growth prospect in the economy and the power sector; (2) there was a clear and steadily improving regulatory framework; and, (3) there was a vibrant domestic private sector which was interested to participate.

Eventually (in 2007), there were a sufficient number of eligible bidders, who were convinced of the quality of the regulatory framework and the integrity of the competitive process. The National Grid Corporation of Philippines (NGCP), a corporate vehicle of a group of local and international companies, won the concession.

Predictable Transmission Tariffs Set the Stage for Transmission Company Concession in the Philippines

“The efforts to attract investors to the Philippine transmission business were an essential part of the government's electricity reform programme stipulated under EPIRA in 2001. However, the efforts to complete the required auctions failed twice in 2003, and then again in February 2007. Regulatory uncertainty about the transmission company's revenue streams was the main concern voiced by investors, even though the transmission company had published the first set of essential guidelines on the subject. The failure of the first two bids can be attributed to the short track record of ERC and its PBR methodology. An additional source of uncertainty for bidders was the relatively short (three-year) duration of the first regulatory period set by the tariff guidelines. The period would end on December 31, 2005, after which the rates would be subject to revision.

For the second (2006-2010) and third (2011-2015) regulatory periods, the revenue cap methodology still applied. However, the regulatory uncertainty remained high in 2006, as the specific revenue cap levels were still debated. The continued uncertainty undermined the bidders' confidence, and the government finally decided to drop the third tender in February 2007 when only one bidder remained. At this point, the government preferred to announce a new auction rather than negotiate directly with the sole remaining bidder. The ERC used the opportunity to better prepare for the next auction. The regulatory asset base (RAB), a key component in the estimation of the maximum allowable revenue, was established and could be used by investors in preparing their bids. This set the tone for transparency and predictability of ERC's regulatory process.

The payment of the initial concession fee was made easier by requiring an upfront payment of only 25 per cent and the deferred payment of the balance under precise terms and conditions set before the final bid. In the new auction in December 2007, the successful bid by NGCP yielded $3.95 billion, well above the RAB level that was set around $3.0 to 3.2 billion.” (World Bank, 2015, p. 8)

How It Works

Procuring a whole-of-grid concession

Host countries that seek to implement a whole-of-grid concession may procure them (1) by conducting an international competitive tender or (2) through direct negotiations. In both cases, the process would likely be subject to laws governing the procurement and/or public-private partnerships. MDBs and donors providing concessional financing often find it easier to support infrastructure projects that have been procured following a competitive tender process.

In a competitive tender, the qualification and evaluation criteria of the tender determine the selection of a concessionaire. Where a concession fee is required to be paid either upfront or periodically over the term of the concession agreement, the price offered for the concession fee will likely be a significant consideration in the award of the concession as well as the concessionaire’s return expectations.

For more information on how to procure projects in the power sector, see the Understanding Power Project Procurement handbook.

Planning

The implementation of a concession will impact the process of planning the development of the transmission system. Given the duration of a whole-of-grid concession and the concessionaire’s role in investing in network expansion, the concessionaire will likely become a key stakeholder in system planning. Under traditional cost of service regulation, a concessionaire may have a strong desire to obtain some form of commitment from a regulator that the regulator will include the capital costs associated with a future project in the rate base when the project is placed into service. Under performance-based rate-making, a concessionaire may be required to submit periodic business plans to the regulator which outline the new projects it intends to undertake. Those business plans are in turn used to establish the annual revenue requirements for the period that is covered by the business plan.

Concession fees

A concession agreement typically provides that the concessionaire will pay upfront or ongoing concession fees to the transmission utility. A concession fee provides a source of revenue to the transmission utility which it can use to fund its ongoing costs. A balance must be struck between how much the transmission utility needs to recover against the impact on transmission fees to the system: generally, higher concession fees will lead to higher transmission charges.

At the same time, it is important to recognise that the transmission utility may have ongoing liabilities which may not have been transferred to the concessionaire, for example, servicing a pre-existing debt. The transmission utility would need to earn revenues that are sufficient to enable it to pay for these liabilities as they come due. There may also be ongoing costs incurred by the transmission utility throughout the concession period, including administrative overhead to enable it to administer the concession agreement, maintain its ownership interest in the transmission system, and servicing debt repayment obligations.

There are different options that a transmission utility may choose to charge a concession fee to a concessionaire to extinguish or meet its ongoing liabilities, which are discussed in the Table 6.1.

|

Option |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Option 1 |

Under this option the concession fee would consist of:

The transmission utility would use the up-front payment to retire its debts and would use ongoing payments to fund the ongoing expenses for the term of the concession. The regulated asset base of the concession would initially be established as the amount of the up-front payment. That portion of the regulated asset base would depreciate at a specified rate designed to balance the competing interests of reducing the regulated asset base and reducing the depreciation charge recognised in each annual revenue requirement. |

|

Option 2 |

The concessionaire does not pay an upfront concession fee because the transmission utility retains its RAB, which would continue to depreciate following the regulatory concepts discussed in Option 1. The concessionaire will continue to collect revenue from the customer base, and remit via the concession fee that portion owed to the transmission utility to cover its debt obligations and ongoing administrative overheads. The concessionaire will start to earn a return on new investments made (including depreciation) for capital expenditure investments in upgrades or greenfield transmission network extensions. |

|

Option 3 |

The concessionaire does not pay an up-front concession fee to the transmission utility. The ongoing concession fee paid to the transmission utility will be sized to cover two distinct components:

|

Any number of permutations of these three options could be used to set the concession fee in a manner that aligns with the priorities of the host country and the ability of the concessionaire to raise debt and equity to fund any up-front and ongoing payment obligations. Option 1 would result in the highest upfront payment to the transmission utility (which would likely be paid to the government as a special dividend). In most cases, it would also result in higher use of system fees and therefore higher rates for consumers. Option 3 may, depending on how the debts of the transmission utility are structured, result in the lowest use of system fees and therefore the lowest rates for consumers. Option 2 can be tailored to achieve the desired blend of those two outcomes. Which option a government should pursue depends on its objectives.

Stakeholders

Identifying and mapping stakeholders and their likely interests, concerns and objectives is an essential first step in determining groups of stakeholders that may support or oppose a whole-of-grid concession, with proper stakeholder engagement. To ensure successful implementation, it is important for the team responsible for structuring the concession to consider reasonable concerns and objectives of all affected stakeholders. These stakeholders include the host government (notably the ministries responsible for finance and electricity), the regulator, the transmission utility, generators, distribution companies, and consumers, along with potential lenders who have extended loans to the transmission utility. The most significant effects on those participants are mapped in the matrix that follows in Table 6.2.

|

Sector Participant |

Role |

|---|---|

|

The ministries involved in financing and executing new transmission implementation will now need to pay for and administer any subsidies, if required, to make the concessionaire whole. They will need to plan to raise the termination payment/ “buyout price” at the end of the term or upon the earlier termination of the concession. |

|

Regulators in SSA generally have significant experience regulating publicly-owned utilities, but limited experience regulating privately-owned utilities. A higher degree of oversight is required for privately-owned concessionaires, including regulatory methodology and KPIs, to ensure fairness and transparency. As private sector participation is introduced, both the independence of the regulator and the technical proficiency of the regulator become more important. |

|

The transmission utility will primarily be responsible for administering the concession agreement, maintaining its ownership interest in the transmission system, and servicing liabilities it retains. The concessionaire may be required to hire substantially all of the transmission utility’s employees as a concession condition. In all cases, employment considerations would also be influenced by local law requirements, impacting costs. |

|

Connection agreements and TSAs between generators, distribution companies, and industrial customers and the transmission utility will need to be transferred to the concessionaire. Consideration will be required regarding impact to generators, distribution companies, and industrial users, including liability for grid interruption and unavailability. If the transmission utility performs the role of a single-buyer and has entered into power purchase agreements in respect of independent power projects, those agreements should be reviewed to determine whether the implementation of the concession will trigger any defaults under existing PPAs. |

|

Development finance institutions that fund, or may be interested in funding, the development of new transmission infrastructure will be interested in exploring how they can continue to fund the development of new transmission infrastructure after the concession has been implemented. |

Contractual Structure

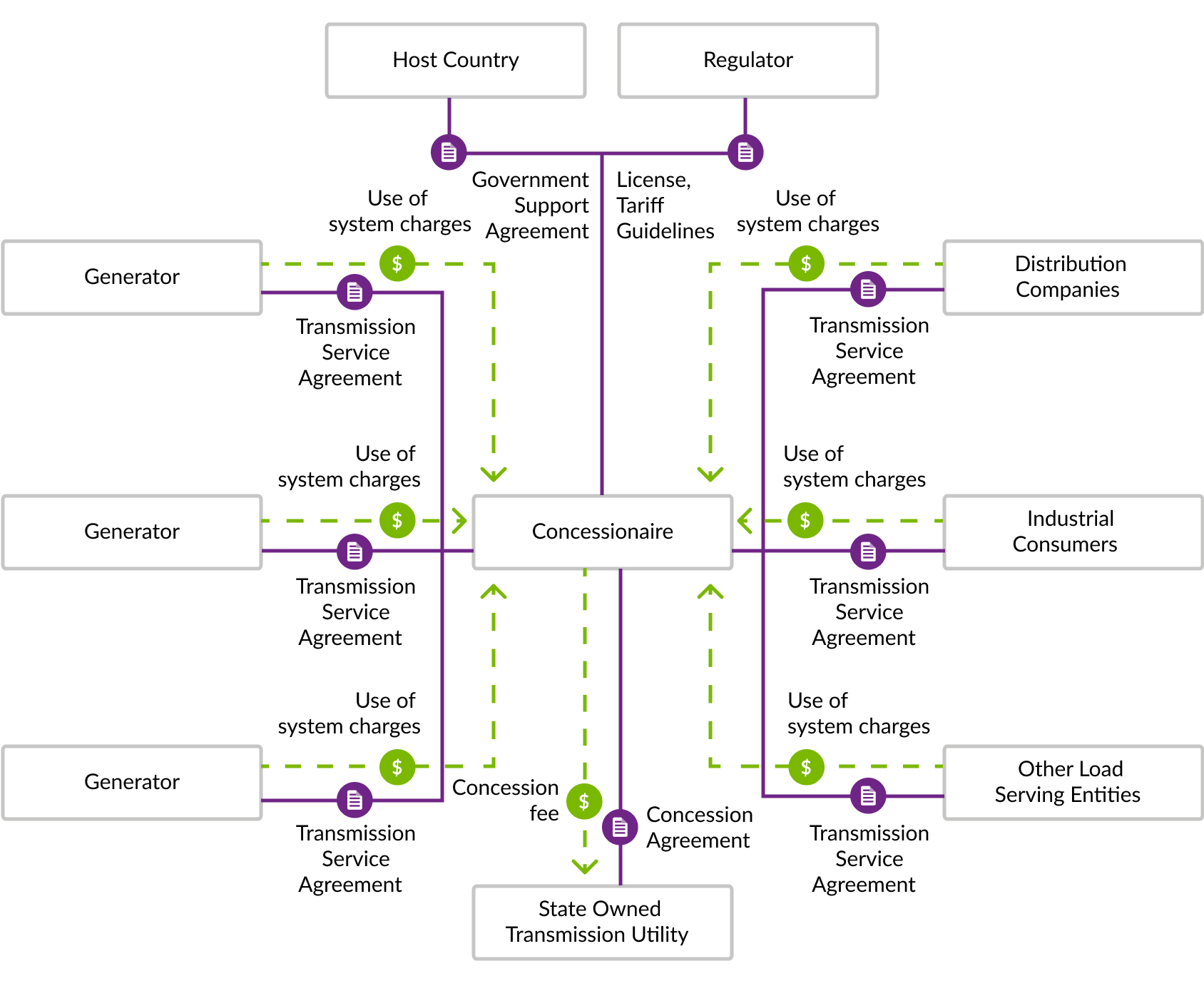

The participants in a concession and their contractual relationships are shown in Figure 6.2. The structure presented in Figure 6.2 assumes that the state-owned transmission utility does not act as a single buyer. If the state owned transmission utility does act as a single buyer then additional contracts will be necessary to separate rights and obligations related to transmission from rights and obligations related to supply.

As the concessionaire constructs and installs new equipment and facilities and those facilities become part of the transmission system, legal title to the new equipment and facilities vests in the transmission utility so that the transmission utility remains the owner of the entire transmission system during the term of the concession. If, for example, the concessionaire needs to acquire additional rights-of-way, easements, ownership interests, or leasehold interests in land to expand the transmission system, the concession acquires those interests in the name of the transmission utility, and those interests become subject to the leasehold interest and access rights created by the concession without further action by the concessionaire or the transmission utility.

The concessionaire will be responsible for operating and maintaining the transmission system. If the legislative framework provides that the holder of a transmission license is responsible for dispatching generation and balancing the system, then the concessionaire will be responsible for those functions. If the legislative framework contemplates that those functions will be performed by a transmission system operator, then those functions will be performed by the entity that holds the license to act as the transmission system operator. Although the concessionaire may also hold the license to act as a transmission system operator, a different entity will perform those functions in markets that separate the transmission ownership and transmission system operator functions.

The concessionaire will recover its ongoing operations and maintenance costs from the use of system fees it charges for transmission. It will finance capital expenditures to upgrade and expand the transmission system with a combination of debt and equity. Equity will be contributed by the shareholders in the concessionaire or created by the retention of earnings by the concessionaire. The concessionaire will raise debt by borrowing from lenders or by issuing bonds or preferred shares. The concessionaire’s ability to raise capital in the form of equity, debt, and preferred shares is highly dependent on how the concessionaire is regulated.

Key project agreements

In a typical whole-of-grid transmission concession, a state-owned utility that owns a transmission system (the “transmission company” or the “transmission utility”) grants a concession over all or a portion of its transmission network to the project company established to act as the holder of the concession (the “concessionaire”). At the same time, the ministry that is responsible for overseeing the electricity sector or the Independent Regulator that regulates the electricity sector, if one has been established, typically grants a transmission license to the concessionaire. In addition, the host country may enter into a government support agreement, implementation agreement, or similar agreement (a “government support agreement”) with the concessionaire to provide certain identified types of support to the transaction. We explore these three key documents below. We also take a look at a key concept for the financing of whole-of-grid concessions, and termination payments, below.

Concession agreement

The concession agreement will typically provide that:

- The transmission utility will retain ownership of the existing transmission system but will concede and/or lease the existing transmission system and related immovable assets that are useful for operating and maintaining the network and are used by the transmission utility for that purpose to the concessionaire for the life of the concession.

- The transmission utility will lease or sell to the concessionaire all of the transmission utility’s moveable property, equipment, and inventory of spare parts.

- The transmission utility will transfer its right, title, and interest in some contracts to which the transmission utility is a party, which may include ongoing service contracts, contracts for the supply of goods and equipment, and contracts for the construction or supply of new assets that will become a part of the transmission system.

- The concessionaire will pay a concession fee, which may be structured as a one-time payment, ongoing payments, or a combination thereof, in exchange for the concession rights that have been granted to it.

- The concessionaire will use the leased or transferred assets to provide transmission services within the host country (or part of it) as described in the transmission license.

- The concessionaire will improve, repair, operate and maintain the transmission system, and

- The concessionaire will expand, reinforce, and upgrade the transmission system to the extent required to provide transmission service within the relevant host country, and to the extent that expansion projects are approved by the regulator per the tariff guidelines.

Government support agreement

As far as a whole-of-grid concession is concerned, government support agreements will cover similar risks as in IPTs — although they may have additional and specific protections relating to any outstanding risks that fall to the government concerning an entire transmission system including, for example, pre-existing liabilities that relate to the transmission system assets before they are handed over under the concession.

Termination payments

The concession agreement and/or the relevant government support agreement will include a termination payment or “buy-out price”, which is payable at the end of the term of a concession or earlier, upon certain early termination events.

This payment amount, if paid at the end of a concession, may often be set to equal the regulated asset base as of the end of the last year of the concession. In scenarios other than the expiration of the term, the termination payment could be calculated by applying a multiplier to the regulated asset base.

In the case of early termination of the concession following (i) an event of default by the state-owned transmission utility under the concession agreement, (ii) an event of default by the host country under the government support agreement, or (iii) the occurrence of a prolonged political force majeure event, the multiplier may be greater than 1 in order to provide an incentive for the host country and the transmission utility to perform their obligations under the project agreements. Similarly, in the case of early termination of the concession following an event of default by the concessionaire, the multiplier may be less than 1 in order to provide an incentive for the concessionaire to perform its obligations under the project agreements. The incentives created by a multiplier other than 1 should not be viewed as, or sized in terms of, a penalty, which could be unenforceable under the laws of many host countries.

Termination payments can be sizeable, as the amount of the termination payment is directly correlated with the amount of investments made by the concessionaire during the term of the concession. On the other hand, a host government may find that a concessionaire has performed well over the term of the concession and that there is little rationale for allowing a concession to expire. A concession agreement and government support agreement may contemplate that the host government, the transmission utility, and the concessionaire may agree to extend the term of the concession before its expiration.

Transmission licence

The concession agreement and Government Support Agreement may contain only a part of the obligations of the concessionaire. Other obligations the concessionaire will need to perform are likely to be set out in the wider legislative framework, including any implementing regulations issued under the regulatory framework, and any licences issued to the concessionaire by the regulator.

Some of the issues the licence may address particular to a concession include:

- The geographic service territory over which the concessionaire will be responsible for transmitting electricity and the nature and scope of any exceptions to the concessionaire’s exclusive right to own, lease, construct, or operate a transmission system within the service territory.

- The term of the licence (which should be aligned with the term of the concession).

- The KPI that apply to the concessionaire and the amount of any fines the regulator may levy in the event the concessionaire does not meet the KPI.

- The scope of the concessionaire’s obligation to expand the transmission system.

- If the concessionaire will perform the role of a transmission system operator, any obligations that are specific to that role, such as an obligation to comply with a grid code or dispatch code.

- Any transition provisions, which might include an agreement by the regulator to forbear enforcing KPI during a limited and defined period at the beginning of the term if the transmission utility has not been able to consistently meet or exceed the key performance indicators.

These obligations will need to be aligned with the concession agreement (or conversely, the concession agreement needs to be aligned with the requirements of the licence). The rights and obligations that are set out in the transmission licence will impact the risk assessment of potential investors in the concession, the bankability of the transaction, and the service levels consumers should expect of the concessionaire.

Risk Allocation Matrix

Many of the risks that arise in the context of a concession are described and discussed above. Please note that the facts and circumstances surrounding a particular whole-of-grid concession will impact how risks are allocated. The risk matrix below summarises how key risks might be allocated to different stakeholders within a concession agreement. For a more detailed discussion and commentary on the individual risks, especially as they pertain to private investment in transmission infrastructure, please see chapter 11. Common Risks.

Please note that the table below is indicative, and not meant to be exhaustive. The precise risk allocation between the parties on any particular transaction can vary from what is presented below. Risk allocation is always subject to the fact pattern existing with a particular transaction, investor appetite, and what risks a government is prepared and able to support on a particular transaction.

|

Risk |

Stakeholder bearing risk |

||

|---|---|---|---|

Govt/Transmission |

Concessionaire |

Consumers |

|

|

Financial risk |

|||

Demand risk |

|

|

|

Credit risk |

|

|

|

Inflation |

|

||

|

Interest rates |

|

|

|

|

Foreign exchange rates |

|

|

|

|

Termination payment |

|

||

|

Land |

|||

|

Pre-existing environmental conditions |

|

||

|

Pre-existing defects in title |

|

||

|

Land acquisition for expansions |

|

||

|

Technical risk |

|||

|

Construction and commissioning of new assets |

|

||

|

Scope changes before/during construction |

|

|

|

|

Interface between transmission infrastructure and generation facilities |

|

||

|

Technical risks related to technology risk |

|

||

|

Operation, maintenance, technical performance |

|

||

|

KPIs, service levels |

|

||

|

Accidents, damage, theft |

|

|

|

|

Social and environmental risk |

|||

|

Social and environmental impacts |

|

||

|

Occupational health and safety |

|

||

|

Resettlement |

|

||

|

Non-political force majeure events |

|

|

|

|

Political and regulatory risk |

|||

|

Initial issuance of licenses, permits |

|

|

|

|

Renewals, modifications |

|

||

|

Changes in law |

|

||

|

Changes in tax |

|

||

|

Political force majeure events |

|

||

|

Disputes |

|||

|

Resolution of disputes (contractual) |

|

|

|

|

Resolution of disputes (tariff methodology) |

|

|

|

Financing a Whole-of-grid Concession

Financing models for whole-of-grid concessions

Network industries require ongoing investment. Ongoing investment requires ongoing increases to the equity invested in the business and ongoing increases (and repayments) of debt. Project finance structures are not well suited to ongoing and open-ended borrowing. For this reason, network utilities with ongoing investment requirements are, as a general rule, financed using corporate finance, not project finance. This has several implications. For example:

- the range of debt-to-equity ratios that can reasonably be achieved using corporate finance is lower than the range of debt-to-equity ratios that can be achieved using project finance;

- the tenor of corporate loans are significantly shorter than the tenor of project finance loans;

- unless a corporate borrower issues bonds, the interest rates on its debt obligations are, as a general rule, floating rates; and

- corporate borrowers have a constant need to borrow to roll over their debt obligations.

Given these implications, large utilities have active borrowing programmes that may result in the issuance of multiple series of bonds and multiple borrowings under lines of credit or fixed-term loans during each year. This should not be surprising, given that project financing techniques were developed in part to increase debt-to-equity ratios, increase tenors, and enable borrowers to hedge their exposure to floating interest rates.

Viability gap funding

A significant portion of greenfield transmission infrastructure has been financed by donors and concessional financing from MDBs.

A whole-of-grid concession does not preclude donors and MDBs from still financing new transmission infrastructure build, nor does it change the role of DFI or ECA lending for new transmission assets. Transmission assets that continue to benefit from donors or other external financings can still be operated by the concessionaire.

Donor funding can also provide viability gap funding to help support a concessionaire’s acquisition of a regulated asset base, with the remainder of the funding being financed by the concessionaire. The concessionaire would earn a return on the portion of the asset base it has self-financed, but not a return on the donor portion of the financing. The blending of donor or concessional capital in this way helps subsidise the cost to the concessionaire of operating and maintaining sections of the transmission network which may be less commercial or in a poor state.

Other Considerations

This chapter has discussed the whole-of-grid concession in the context of concessioning the operation, maintenance, and expansion of the transmission network on a standalone basis. In reality in Sub-Saharan Africa, there are only a handful of examples where the transmission network has been concessioned, and generally, this has been the case when it has been bundled along with generation and distribution services. At the time of writing, there are no whole-of-grid private sector concessions in the transmission sector operating in the African continent, although globally there are multiple examples, including in the Philippines and parts of Latin America.

If power generation, transmission, system operator and distribution remain the responsibility of vertically integrated power utilities, as is the case in many African countries, whole-of-grid concessions in the transmission space may only follow once the sector has been unbundled, or if the entire energy sector is the subject of a concession. This has been the case, in Cameroon, between 2000 and 2015 with AES-Sonel.

In countries where generation, transmission, and distribution are unbundled, system operators are still challenged in their ability to charge cost-reflective tariffs to end users required to enable upstream, midstream and downstream activities in the energy value chain to recover their costs. This is an argument for granting concessions concerning “bundled” assets — so that the generation tariffs can cross-subsidise those on the transmission side, for example.

However, incentivising the private sector by enabling them to be able to charge end users to recover the costs required to build, own and operate entire energy systems is not straightforward given the high capital costs involved and challenges in recovering costs from end users which then do not prohibit access to the electricity.

As a host country considers whether a whole-of-grid concession is an appropriate approach for helping to finance new and existing transmission infrastructure capital expenditure, it should consider (i) how its energy sector is structured, (ii) the role of electricity sector stakeholders and how their responsibilities may be impacted, and (iii) how to engage existing stakeholders to build support for the successful implementation of this approach.

A whole-of-grid concession may be appropriate if a host country desires to:

- leverage the experience and know-how of the private sector to improve the technical and commercial performance of a transmission utility;

- relieve budgetary constraints by transferring the responsibility for financing capital expenses to the private sector for the development and construction of the projects that are required to expand, reinforce, and upgrade the transmission system; and

- retain long term ownership over the transmission system.

A whole-of-grid concession may be less attractive to a host country that:

- has an existing transmission utility network whose performance equals or exceeds international performance benchmarks; and

- is targeting financing for a discrete or a package of transmission infrastructure assets that might be more efficiently financed via IPT

Summary of Key Points

- A whole-of-grid concession grants a private party the right to develop, construct, operate, and maintain transmission infrastructure in a defined geographic area, which is usually but not always an entire country.

- A whole-of-grid concession may be appropriate where the government expects that a concessionaire can: (i) better maintain and operate the existing transmission network, and (ii) raise the capital needed to finance extensions and upgrades to the network.

- The private concessionaire derives their revenue from charging of transmission use of system fees to generators, distribution companies, and industrial users with a direct connection to the transmission system.

- The fees charged by a private concessionaire are usually established by an independent regulator pursuant to a set of tariff guidelines or a tariff methodology that is developed specifically for the concession.