7

Other Private Funding Structures

Introduction

In this chapter, we describe other private sector-led models of procurement for transmission infrastructure, namely:

- merchant transmission lines

- industrial demand-driven model, and

- privatisations

These models are described to ensure that the spectrum of private participation options is covered by the book, although the authors believe that these models are less likely to be adopted or operationalised in the near term in the African context given other priorities of the sector. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that they form part of the future transmission infrastructure story in the African continent.

Merchant Transmission Line

A merchant transmission line consists of one or more lines that connect existing transmission grids/power markets or consumers that were previously isolated. Such transmission lines are entirely private in the sense that ownership, control, financing, construction, operation, maintenance, and tariff setting of the lines rests entirely with the private developer. Access to the merchant line is at the discretion of the owner. Therefore, it is not open to all transmission users.

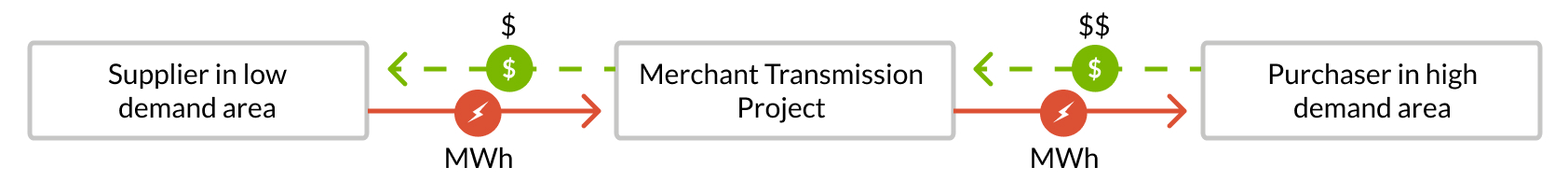

Traditionally, merchant lines were developed by independent companies seeking to use the system to wheel power between markets where there is a difference in electricity prices. Trading power from lower-priced markets into higher-priced markets allows the company to profit from pricing arbitrage. This model of financing is a market-driven model to provide transmission infrastructure that supports competitive wholesale markets for electricity. However, this model may not be viable for markets where tariffs are set at artificially low levels or where there are low-cost production sources. In such electricity markets, the price differential, which the merchant model depends strongly on, is either non-existent or sufficiently insignificant to impede the company’s ability to recover its investment.

Merchant lines are usually not part of the traditional planning of a transmission system but are instead born of market opportunity. However, despite their opportunistic nature, regulators and policymakers still need to put in place the proper regulatory and market framework that supports merchant lines if this is an option they want to pursue to incentivise alternative financing for new transmission build.

How it works

The assets of a merchant line/system are entirely owned by the private party who invests or finances its construction. Merchant lines are generally new construction, though it is conceivable that an existing line/system is privatised and sold to a private party for them to maintain and operate. The state-owned utility responsible for transmission infrastructure has no financial interest in the merchant line.

Despite the private ownership, merchant lines are still subject to technical compliance with grid code (if in place) and regulations in the same manner as all power system assets. This includes approvals on siting/permitting, design and technology to ensure safety, alignment, and efficiency in the national power system. The extent to which a merchant line is subject to regulation is primarily a function of the regulatory framework of the host jurisdiction(s).

The merchant/line system is also privately managed and controlled, with the owner/developer:

- determining when to utilise the capacity of the line to transmit power between markets;

- directing all dispatch, operational, maintenance and repair determinations for the line(s); and

- negotiating commercial agreements, including pricing, with the transmission systems on either end of the line to secure grid access.

Merchant line developers are responsible both for the initial capital costs to purchase the rights-of-way, design and construction of the project, and for ongoing operations and maintenance costs. The commercial viability of a merchant line rests entirely on its ability to capture value through power pricing arbitrage across markets or by selling its capacity to third parties. In promoting this model, advanced transmission network planning and coordination is important. Also, there will be requirements to review policies that do not accommodate a decentralised competitive wholesale market.

To secure a revenue source, there are three potential avenues for securing customers in the merchant model.

- Bilateral negotiation with a potential anchor credit-worthy customer;

- Competitive sale process with credit-worthy participants bidding; and

- The real-time market mechanism through short term sale of the firm and non-firm capacity, leveraging price arbitrage.

The customers of a merchant line owner/operator may include existing generating company or generation project developers who would buy the merchant transmission service to deliver the power from their generation plant. The customers may be utilities, retailers or load-serving entities with energy needs becoming anchor tenants giving them access to an energy source. Also, customers of merchant lines may be energy traders or owners of merchant generation assets that want to take advantage of arbitrage congestion. More so, the implementation of the merchant model is only possible where private entities are allowed to hold a licence for the construction and operation of a transmission infrastructure among other regulatory requirements.

There have been a limited number of merchant transmission lines globally. Examples include a transmission line between the Australian state of Victoria and the island of Tasmania; Path 15 connecting the northern and southern sections of the California power grid; and Montana-Alberta Tie Line.

Key challenges to adopting the merchant line model

The most significant challenge to financing merchant transmission lines is that it will be challenging to secure the project revenues for the financing. Hence, a private company might need to finance the project with little or no leverage (debt), or based on other commercial activities. This is not optimal for the size of the investment required for transmission assets.

This model may be attractive for governments depending on the needs of the specific country. However, even if there is a well-functioning market with limited credit risk (such as the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) market, where settlements are prepaid), there still needs to be a consideration for broader risk, such as political stability, land acquisition, and environmental and social risk. These risks, coupled with the market demand risk, pose a challenge to most private investors, which return expectations alone will not be able to overcome.

In places where there are no markets like SAPP, the regulations for cross-border trades involving private participants are unlikely to have been fully developed. Without regulatory certainty, it is difficult for the private sector participants to develop a project on a merchant basis, as regulatory certainty is required for long-term investments.

Industrial Demand-driven Model

In the industrial demand-driven model, transmission expansion is driven by the electricity needs of one or more large industrial consumers. The transmission line will be financed, built, and operated to serve the industrial area where the large consumer(s) conduct their businesses. The relevant transmission line, once built, could remain in the hands of the private sector or could be handed back to the transmission utility responsible for the ownership and maintenance of transmission assets (often in countries that consider transmission infrastructure a public good).

As economies develop, there may be growth in a particular industry or the discovery of a commodity in a region of a country where there is little or no existing transmission infrastructure. The development of the industry could underpin wider economic growth, which may be a key driver in the procurement and financing of power and transmission infrastructure to support industrial growth or a significant customer. The key feature of this industrial-demand driven model is that the project will be financed based on the creditworthiness of the industrial consumer(s) and the strength of the industrial sector (e.g., the commodity sector’s prospects).

Industrially driven development may not have initially been part of the government’s overall strategic plan to electrify and connect its population to the power grid. The same pattern is reflected in other forms of infrastructure such as roads and railway lines. Particularly where commodities are involved (e.g., mines or extractive industries) or where there is a burgeoning industry (often based on a natural resource), the private sector may engage the government to obtain the relevant rights/licences to construct and sometimes operate the relevant power and/or transmission infrastructure. Such lines may also be initially constructed by the government and transferred to the private sector as part of privatisation.

How it works

One or several large industrial network users located within the same area will typically establish or be approached by a project company that will be responsible for financing and constructing transmission assets used to wheel power generated outside the industrial area. The power generator may be a state-owned utility, the project company or another generator that has entered into a standard power purchase agreement with members of the consortium. The project company will prepare a transmission expansion proposal for submission to the government regulator. Depending on the structure of the transaction, the costs of the network are allocated to (or among) the industrial user(s) either based on a method established by the regulator or a method agreed upon between the project company and the industrial user(s) at the time the project company was established.

The industrial demand-driven model is similar to the merchant line model in that it is subject to regulatory approvals on siting/permitting, design and technology to ensure safety, alignment, and efficiency in the national power system. Moreover, the project company will also typically set the price for access to the line, subject to regulatory approval.

However, unlike the merchant line model, the business case for the industrial demand-driven models is based on the creditworthiness of the industrial users of the network. Hence, the demand risk associated with the merchant line model is reduced in the industrial demand-driven model — the line is built primarily by or for the demand.

While the industrial demand-driven model is not yet a common method for financing transmission infrastructure in SSA, it is included in this chapter as reflective of the “status quo” due to the strategic importance of the mining sector for the development of the continent.

Key challenges to adopting the industrial demand-driven model

A key challenge to adopting the industrial demand-driven model is determining the mechanisms for granting access to other network users that are not the industrial users. It is inefficient to have multiple transmission assets located in the same route. Hence, when the country’s electricity demand increases, it may become necessary to use the industrial demand-driven line to service distribution networks or other generation companies located close to the line. When approving an industrial demand-driven line that will be owned and operated by a private company, the government has to anticipate a possible increase in demand which will necessitate general use of the line. This will enable an initial determination of how costs will be generally allocated in the future when the line is opened to all transmission users.

Privatisation

Privatisation, otherwise called full divestiture in the context of this handbook, relates to the transfer of full ownership in the transmission infrastructure to a private-sector party. Privatisation may occur on a single transmission corridor, by region or even in respect of the entire transmission system operation in a country. Once privatisation has taken place, the transmission company is typically restructured, management processes are re-aligned, technology and infrastructure investments are planned and the government influence on the operation and management is limited to regulatory activities.

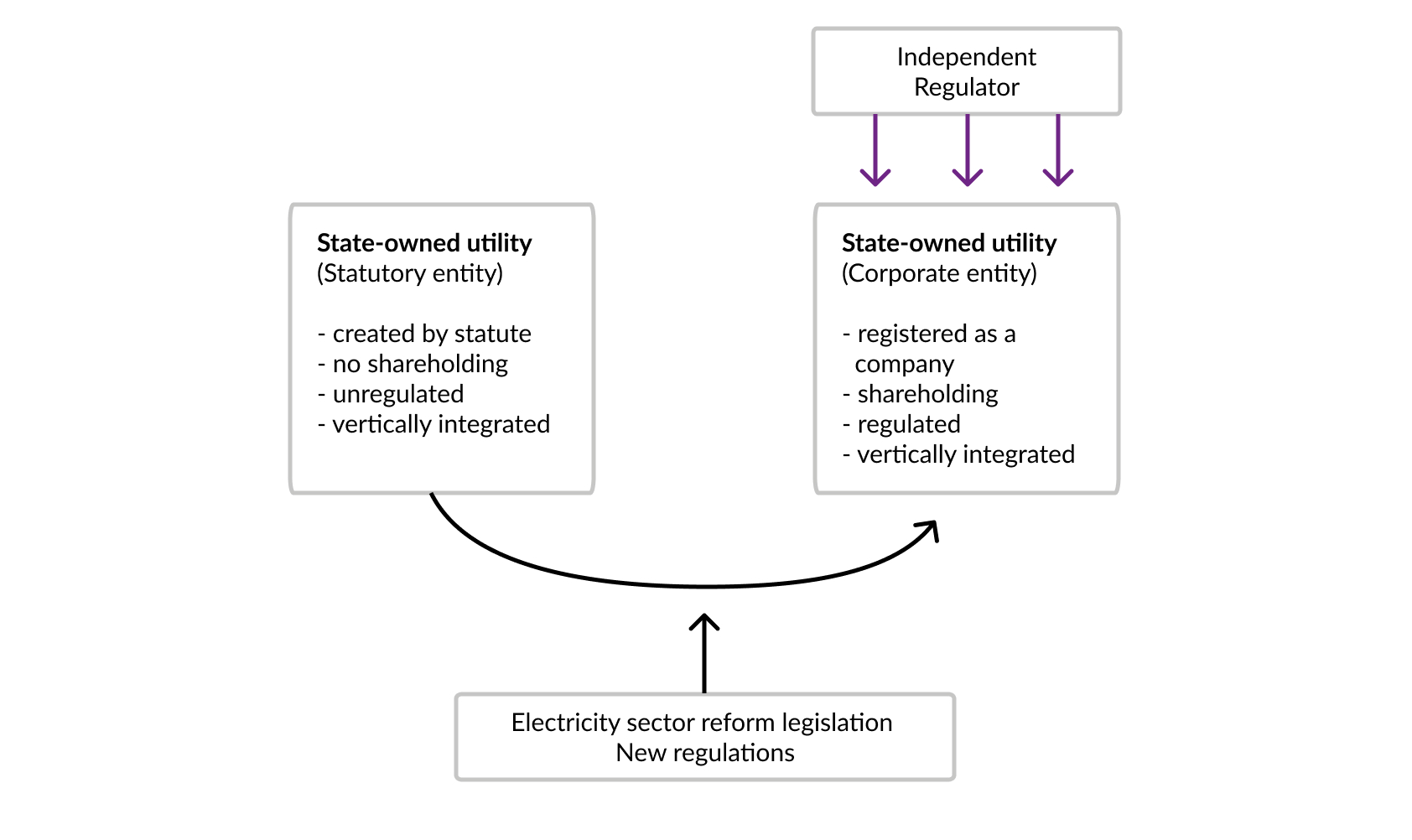

In deciding whether to privatise the transmission segment of its electricity supply industry, a government should carefully evaluate its goals for the sector and whether privatisation is the best model for achieving these goals. Since the transmission business is typically considered a natural monopoly, specialised regulation will be required to monitor the activities of the privatised transmission business. Further, the process of unbundling the vertically integrated utility, breaking it up, and privatising the transmission segment will take considerable planning, political will, and appropriate legal reforms.

Privatisation may be an option to be considered under the following prevailing conditions:

- where there is a partial or full legal unbundling of the transmission system operating function;

- where a private-sector party is allowed by law to hold a transmission licence for the construction and operation of the transmission infrastructure; and

- where there is an independent regulator to ensure technical compliance and ensure appropriate tariff structures.

In other words, privatisation is more suitable to those jurisdictions that have already commenced some form of unbundling and electricity sector reform, and where the regulatory framework is conducive to private sector participation in providing transmission-related services and private sector ownership of the transmission assets (or where policy decisions have been made to effect the above changes).

How it works

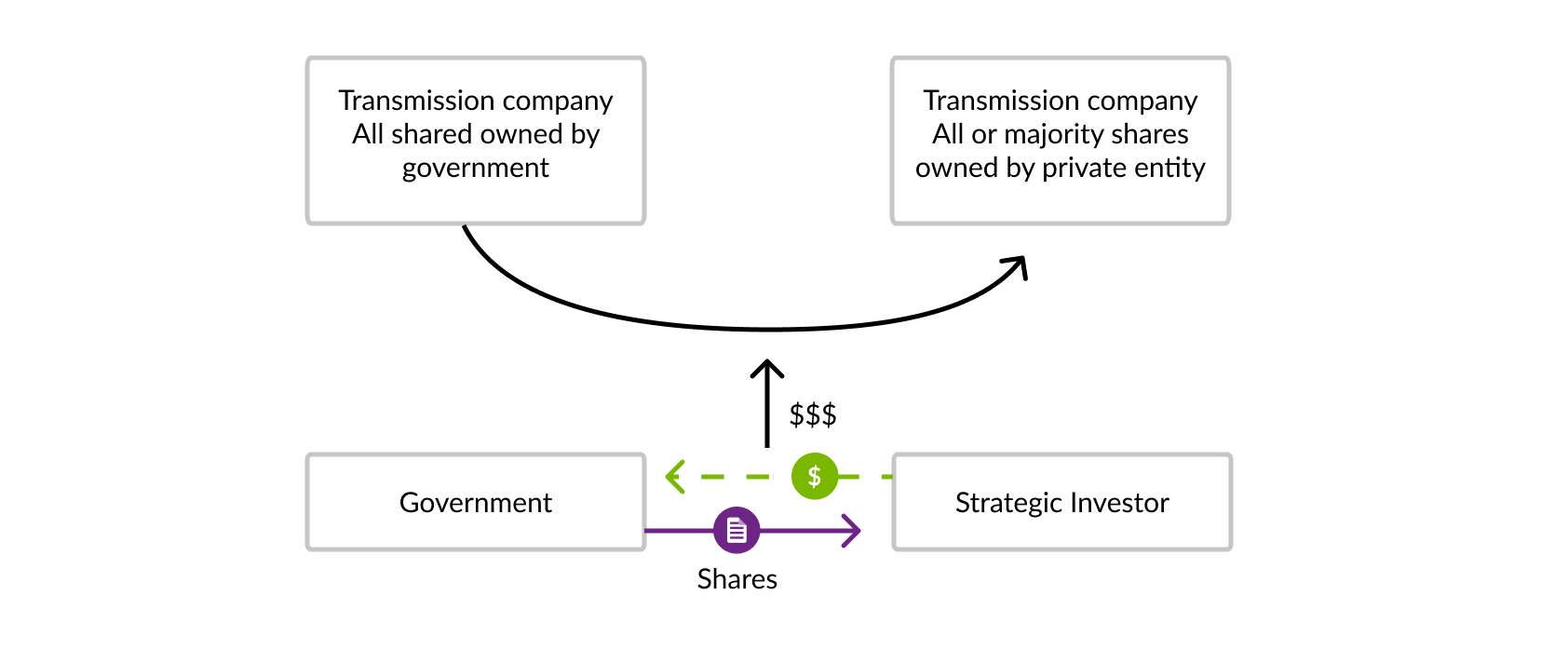

Privatisation can be implemented in at least three ways:

- A sale of shares — where all or a majority of the shareholding of the existing transmission company is transferred to a private entity. In this option, the existing transmission company and its licences remain unchanged and the transfer occurs at the shareholding level;

- A sale of assets — where there is a sale of the transmission business as a going concern. In this option, the private party would be expected to form a new transmission company and acquire the relevant transmission licences in the name of the new entity; or

- A statutory transfer — where legislation is passed imposing a compulsory transfer of the transmission assets or shareholding, to a private party. In this option, the transfer would be prescribed by the legislation and any conditions attached to such law.

The government and the new owner may also enter into a government support agreement, which protects the new private sector owner from certain risks such as change-in-law, expropriation and foreign exchange.

Key challenges in adopting the privatising model

One of the key decisions that governments need to take at an early stage is to be willing to divest from owning transmission infrastructure that are assets with national security implications. This will entail the loss of ownership in assets that are monopolistic in nature. This monopoly does provide governments with intense power to control the electricity supply of a country and provides for additional revenues in some instances.

A second challenge is a fear that the privatisation process will result in increased tariffs. A carefully managed privatisation effort will ensure that results from long-term financial models are clearly articulated to the public and key stakeholders. In some instances, there may be an initial tariff increase due to increased operations and maintenance activity and investments required to stabilise the transmission business. However, long-term benefits and comparative cost reductions need to be proven and stated. The usual intent of a privatisation process is to increase the efficiency and stability of the transmission business, which could ultimately lead to relative cost reductions. If this is not achieved, the re-nationalisation of the privatised transmission assets are likely to bring even more challenges to the country’s power sector.

Another challenge is that staff and management of public utilities in some instances fear the loss of jobs. However, some means are available to governments and unions that can be utilised to guarantee job security. If managed carefully and when widespread stakeholder buy-in is secured, this challenge can be minimised. However, this is a fundamental challenge and staff resistance may be at a level that may be too difficult to overcome.

Case Study — The Copperbelt Energy Corporation (“CEC”)

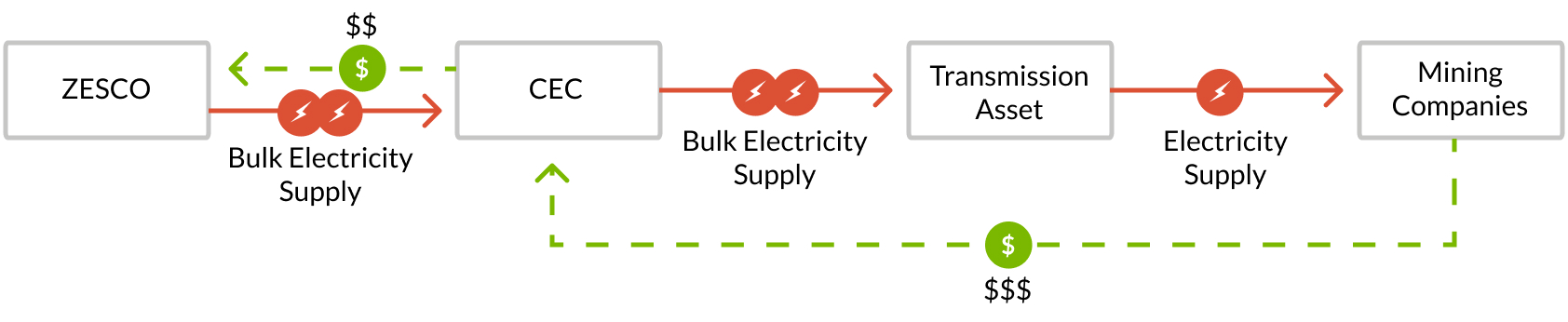

CEC’s business model has features of all three models — the privatisation, the industrial demand-driven model, and merchant line models — but especially, the industrial demand-driven model. CEC was established as part of the privatisation of a previously government-owned mining company. CEC’s transmission assets were built primarily for the defunct mining company’s electricity demand, and CEC currently sells power wheeled through its network to many mining customers in Zambia. Further, CEC currently buys or generates power in Zambia at a relatively lower cost and sells to mining companies in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

CEC is a private company established in the context of the privatisation of the Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM) in 1997. Before being privatised, ZCCM owned and operated electricity assets through its power division to address the needs of its mining operations in the Copperbelt region of the country. When privatised, ZCCM was divided into several companies and CEC took on the activities of ZCCM’s power division including the role of operating, maintaining, upgrading, and expanding the transmission asset to continue the supply of electricity to the mines. CEC was later listed on the Lusaka stock exchange in 2008 and became a full member of the Southern African Power Pool in 2009.

CEC currently owns a network of more than 1,000 kilometres of transmission lines at 220kV and 66kV, 43 high voltage substations and a transmission interconnection between Zambia and the DRC. The company purchases electricity from ZESCO, the Zambian national power utility, and sells this across its transmission network to many Zambian mining customers with a combined average demand of approx. 450 MW. CEC also operates 6 gas turbine generators for emergency power supply with a total installed capacity of 80MW.

The business model of CEC is not solely focused on transmission line assets as the company diversified its activities in recent years and has also developed generation projects and conducts power trading activities. Nonetheless, CEC is a good example of an industrial-led funding model as it was set up to address specific needs of the mining industry in the Copperbelt region. Hence, the funding required for the acquisition, maintenance, upgrade, and expansion of the network was provided on the basis of the mining companies’ ability to pay for electricity and the strength of the commodity sector. Moreover, the characteristics of some of the world’s deepest copper mines required consistency of supply to guarantee the safety of the mines’ workers. The reliability standards of the network and the readily available emergency power supply were therefore specifically designed to respond to the specificities of the mining activities.

Summary of Key Points

- Some other private sector-led models of procurement for transmission infrastructure include:

- merchant transmission lines

- industrial demand-driven model, and

- privatisations

- These models are less likely to be adopted or operationalised in the near term in the African context given other priorities of the sector although they likely will form part of the future infrastructure development in the African continent.

- Merchant transmission lines

- A merchant transmission line consists of one or more lines that connect existing transmission grids/power markets or consumers that were previously isolated. These transmission lines are entirely private. Access to the merchant line is at the discretion of the owner. It is not open to all transmission users. Merchant lines are usually not part of the traditional planning of a transmission system but are instead born out of the market opportunity.

- Industrial demand-driven models

- In the industrial demand-driven model, transmission expansion is driven by the electricity needs of one or more large industrial consumers. The transmission line is developed to serve the industrial area where the large consumer(s) conduct their businesses. The relevant transmission line, once built, could remain in the hands of the private sector or could be handed back to the transmission utility.

- A key challenge to this model is determining the mechanisms for granting access to other network users that are not part of the industrial users.

- Privatisations

- Privatisation relates to the transfer of full ownership in the transmission infrastructure to a private-sector party. Privatisation may occur on a single transmission corridor, by region or even in respect of the entire transmission system operation in a country.

- Once privatisation has taken place, the transmission company is typically restructured.

- Challenges to this model include a government's concerns about loss of ownership of its natural monopoly and control, the fear that privatisation will result in increased tariffs and the risk of significant job losses with the public utility.