9

Planning and Project Preparation

Introduction

Transmission systems play a crucial role in moving electricity from power plants to the end users. The farther the plants are from load centres, the more important it will be to plan carefully the development of the transmission infrastructure. With a growing focus on cheaper and greener energy sources that are frequently located in less populated areas, it is becoming even more imperative to efficiently transmit electricity across the grid. In this chapter, we will discuss the following:

- The power system planning process;

- The process for developing a Transmission Development Plan (TDP);

- The need for the planning process to result in the selection of a project with an appropriate financing structure; and

- The process for procuring private sector participants.

Depending on the jurisdiction, the responsibility of the transmission planning may shift from the transmission utility to the ministry, regulator or another governmental agency. It also can be the responsibility of the private sector, although this is rarely the case in SSA. Even in the case of a whole-of-grid concession, the planning function may be retained by the government and the execution of identified projects may be done partly or fully by the public sector and then handed over to the concessionaire.

The transmission planning process also allows the government to identify the transmission lines that will be built in the upcoming years and for which it will allocate significant resources. Thus, the planning process also enables the government to identify lines not considered a priority but that might be suitable for a merchant line or industrial demand-driven funding model (regulation allowing).

This chapter will discuss the various steps from the power system planning phase to the procurement of a transmission asset.

Power System Planning

There are many reasons why a government or a key public sector institution (e.g., transmission system operator) should conduct power system planning. These include:

- Efficiency: to avoid multiple studies and solutions, transmission planning should be done by a central agency of government to better integrate and use energy efficiently.

- Optimisation: to avoid stranded or under-utilised assets in the sector.

- Reliability: to provide reliable power to customers and to avoid underserved customers.

- Cost-effectiveness: a holistic approach provides cost-effective solutions.

Without a plan, there is substantial uncertainty regarding the development of the power sector, and this increases the risks associated with new projects.

The typical process flow for developing a new transmission line is depicted below. This chapter will expand on each of these processes:

Integrated Resource Planning

Integrated Resource Planning (IRP) is usually done by the Government. This is done at a national level to develop a plan to meet all the country’s national energy demands with available and planned supply. It is a planning and selection process for electricity infrastructure development, which assesses all options for providing adequate and reliable electricity service to end users at the least system cost.

Some of the options considered by an IRP include new generation capacity, energy efficiency measures, renewable energy resources, energy storage, and cogeneration. The IRP process considers the impact of any of these options on the efficiency and reliability of the electricity network. An IRP will provide a country with an energy plan for a long period, usually 20 years. Although the IRP has a strong focus on power generation requirements, it does account for high-level transmission costing to connect generation power plants and load to main collector substations.

One of the main objectives of the IRP is to identify the least-cost generation to meet the macro power demand over a defined period. To project the growth of the demand for various energy sources, the IRP will set macroeconomic assumptions such as GDP growth and country inflation targets. The demand needs are then balanced with the country’s potential energy sources and the cost associated with their conversion into electricity. Some power projects that are already being developed will be included in the IRP’s assumptions and used as inputs into the analysis. The shortfall between the anticipated supply and the projected growth will result in identifying opportunities for new generation projects.

The IRPs usually require continuous updates based on changing assumptions (especially demand forecasts and implementation schedule of projects) and government targets. The output from an IRP process serves to strengthen the level of knowledge of the sector stakeholders and simultaneously serves as an input to future IRP processes.

Not all countries in Sub-Saharan Africa produce IRPs. In some instances, they are not detailed. This often leads to the construction of adhoc generation plants. This unplanned approach can produce undesirable consequences such as stranded assets in some areas of the system or the overload of a part of the system. In addition, without a power sector development plan, it would be difficult to identify in advance the need for transmission system requirements. As depicted in the flowchart (Figure 9.1), the IRP is used as an input to the Transmission Development Plan which provides for a more focused study of transmission projects.

Transmission Development Plan (TDP)

The TDP is developed by the transmission utility. In some instances, there may exist an independent system operator but this is not common in Africa.

The TDP utilises the IRP as an input. The TDP is needed to identify specific transmission projects which are required to ensure that the electricity generated reaches the end users and satisfies their needs. The TDP is crucial to the current and future viability of a country’s power sector.

The planning process, as depicted in Figure 9.2, identifies the gap between the capacity of the existing transmission system and the infrastructure needed to meet current and projected demand. This process takes into account several key factors including the historical demand, the quality of power supply, the economic growth and development goals, regulatory requirements, connections to new power plants, system losses, undesirable voltage profiles and new industrial customers with high demand. Regulatory requirements can include the need to meet the quality of supply or system reliability standards or technical loss limits set by the regulator. Regulations including the grid code may also impose obligations on the transmission utility to connect, for instance, renewable energy plants which are typically located in undeveloped parts of the country and away from load centres. All these factors serve as inputs into the analysis of options for transmission system development.

Stakeholders

A wide range of public and private stakeholders with different interests may be involved in the transmission planning process, depending on the structure of the power system and the market operations. The sector’s stakeholders will typically include the Ministry of Energy, the economic planning ministry, power generators, utilities, industrial customers, regulators, the investment community, and the transmission utility(ies). While some of these stakeholders may play active roles in the process (e.g., regulator, utility, cities, etc.), others such as large industrials or building owners may only be consulted as part of the data collection activity or for an alignment of the different options available for resolving identified challenges in the transmission system. Notwithstanding differences in each stakeholder’s level of involvement, all stakeholders need to be aligned in the development of the TDP to ensure that it is a national and comprehensive plan.

Transmission system planning studies

The identification of projects for the TDP is underpinned by many critical studies. The analytical work is mainly done by planning experts. Some of these studies include a demand forecast; load flow studies of existing and future systems; a short circuit analysis; system stability studies; and resilience analysis.

For best results, the team of experts will be composed of different experts such as economists, environmental specialists and engineers experienced in planning, design, operations and maintenance. Existing and prospective power producers must be consulted during this phase of the planning process. The output of the analytical work is a list of projects required to satisfy the evolving needs of the power system, more specifically to ensure that generated electricity is transmitted to end users in the most efficient manner and satisfies the demand needs of end users.

The options assessment generally specifies the type of equipment to be built to improve the stability of the transmission system and the quality of the supply. The assessment will also cover high-level capital and lifetime cost estimates and the useful lives of these components on the network. Lifetime cost may include losses, operations and maintenance costs. The options may also already identify preliminary route surveys and locations and their preliminary environmental and social impact assessment. Detailed cost estimates, identification of actual route of transmission infrastructure, and substation sites are only required for the most viable options during project development (e.g., through the project-specific feasibility study).

Route Identification

At an early stage, satellite images and available topographical data may be used to identify one or a few feasible routes for further analysis and investigation. Routes that have little chance of success such as routes close to communities and nature reserves, can be avoided. When one or a few viable routes are selected, further investigation may warrant on-site activities such as “walking/driving/flying” the route to confirm initial findings. At this stage, environmental screening activities may also start and community consultations are essential. The main outcome of this phase will be the specification of a few routes from identified substations, which are low cost and have low or manageable environmental and social impacts. More detail on route identification, land acquisition and environmental and social impact studies is provided in chapter 10. Land acquisition.

Transmission Project Selection

The next phase of the transmission planning process is the selection of specific projects. In this context, the relative merits of the options and alternatives generated from the analytical work are evaluated and ranked. Considerations other than electrical parameters come into play, including critical factors such as the environmental and social impacts. The options and alternatives are therefore not only compared based on technical efficiency and cost but also according to their environmental, social and regulatory impacts. The set of viable, economical, and environmentally feasible projects selected at the end of this phase constitute the TDP.

The output of the TDP is a list of viable project alternatives for meeting the identified needs of the power system. Out of this list, the projects to be developed are selected. The case study below provides an example of a TDP.

Case Study — Eskom Transmission Development Plan

Eskom’s Transmission business in South Africa is recognised globally for its technical expertise and operations. Over the last 10 years, it has successfully constructed over 7800 km of new transmission lines (added to its existing ~30000 km of transmission lines defined as 132kV and above) and increased the transmission substation capacity by more than 37000 MVA. The transmission business follows a rigorous planning approach. This is depicted in the diagram below (courtesy of the published ESKOM TDP).

To achieve this, Eskom has to carry out many assessments such as conducting strategic Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and strategic servitude acquisition, working closely with the government on the IRP development, independently determining its own national and regional forecast at the Main Transmission Substation (MTS) level, and merging planning data with operational data to ensure that reliability is improved. All of Eskom's planning is also designed to meet the South African Grid code and to ensure that the new generation is integrated. More than 10000 MW of new generation has been integrated into the grid over the last 10 year with a substantial increase expected for the next ten years. Eskom also develops a strategic long-term Transmission Plan that is updated every 2 to 3 years based on long term strategic assumptions over 20 years (instead of the 10-year planning horizon for the TDP which is updated annually).

Project Preparation

The planning process for transmission infrastructure will provide the utility or a ministry with a list of projects for implementation. At this stage, a project can be identified for concept definition and initial design. A typical project will follow the following phases:

Each phase has clear outputs as defined in the diagram above.

It is important to note that in the practice, the transmission planning and project preparation phases will have some overlaps in terms of some of the outputs of the concept phase. However, a clearly defined project concept is a key requirement to attract project preparation funding and technical assistance funding for the further stages.

Pre-feasibility analysis

The pre-feasibility analysis will focus on confirming several assumptions of the TDP route identification process and high-level environment and social impact assessment (ESIA) to confirm (or adjust) the preliminary analyses or conclusions made in the context of the TDP. The pre-feasibility analysis is considered a high-risk phase of a transmission project. It is therefore important to keep costs as low as possible. The project will progress toward a full feasibility study if the outcome of the pre-feasibility is satisfactory.

The private sector is rarely involved at this stage of the project preparation process because of the significant uncertainty surrounding the project’s viability and business case. For this reason, the Government or transmission utility should always budget or seek funding to provide for the cost of the pre-feasibility studies for the projects identified.

Feasibility study

The feasibility study will be conducted on the route selected by the pre-feasibility study and confirms or refines its conclusions through detailed analysis and technical designs. Examples of activities carried out at this stage may include power system analysis to establish the technical feasibility, estimated power flows and scenario simulation for losses under different operating conditions. Other activities include in-depth data gathering, site reconnaissance activities including visual inspection of the route and development of a digital terrain model, alternate route analysis, geotechnical and other advance studies, substation site selection and layout, risk assessment, stakeholder engagement and route selection workshops.

At the end of the feasibility study, the project should have complete initial design and cost estimates, a financial and an economic business case, an ESIA, recommendations of contract procurement packages, legal structure options and an approach for the financing of the capital works. All of these activities will set the scene for project structuring to affirm the bankability of the project.

At this stage, the inclusion of the private sector will be easier and can be considered. However, to attract greater interest, the government or utility can also consider conducting the feasibility study before approaching the private developers. If private participation does not gain traction at the feasibility stage, it should consider alternative public funding options.

Funding for Project Preparation

Even when the private sector is invited to participate in the development of a transmission infrastructure project, the expectation is usually that the Government or the transmission utility will conduct most of the project preparation activities. However, not all SSA governments or SOEs may have the funds to conduct this exercise. For this reason, project preparation funds or facilities (PPF) have been designed to provide funding for the project preparation of transmission lines. Some of these donors/funds have specific objectives such as the introduction of the PPP model or to help promote regional integration, while others aim at encouraging projects that help meet climate change targets. Hence, PPFs are not homogenous. A non-exhaustive list of donors/funders can be found online at The Infrastructure Consortium for Africa.

Some of these fund sources also support capacity building, facilitate and support the enabling environment to support infrastructure investment by the public and private sectors, or a combination of both. It should be noted that multiple funds may be used for the same project. For example, a fund may be used to develop and conclude the ESIA study while another may fund the technical feasibility report.

Most of these donors/funders have standard application processes and documentation. At a minimum, the conceptual phase for the project should be well-conceived before applications are made. Some donors/funders will only fund projects that are ready for feasibility studies and expect the concept and pre-feasibility studies to be complete at a minimum. A high-level understanding of the sites for the substations (if required), line routes, the financial and economic benefits and the expected cost of the project should be understood and documented as a minimum. Linkages to possible private participation, “green” energy and regional integration should also be clearly articulated.

Procurement and the Private Sector

As stated above, the planning and early preparation work is commonly undertaken by the government or state-owned utility. It may be possible to start considering the inclusion of private sector participation at the concept stage of a project. However, in most instances, the high-risk nature of the project will deter most investors.

When the decision has been made to include the private sector, the government needs to consider the procurement approach. This is discussed in the following sections.

Procurement framework

The applicable procurement framework is closely linked to the source of funding for that particular project. If the government or the transmission utility conducts the project preparation (pre-feasibility and feasibility studies) then the sovereign laws, guidelines, and regulations become applicable. If the feasibility studies are funded by grants from donors, then there will be a requirement to waive the local requirements for the procurement and adopt the donor’s requirements. This is often captured in a grant agreement between the government and the donor.

It should be further noted that funding for the capital works must be kept in mind. If funding is sought from DFIs for the capital works, a review of all procurement activities will be conducted. If the local procurement guidelines and regulations do not provide for competitive procurement then it is advisable to adopt AfDB or World Bank guidelines to avoid further challenges in raising finance.

For cross-border projects, choosing a local framework to govern the procurement can be complex. Since most project preparation for cross-border projects are donor-funded, most projects will adopt the donor’s requirements. If there is an instance where development activities are being funded by the government or the TSO, then it is advisable for the project to still adopt an international DFI’s guidelines to secure funding for the capital works at a later stage.

Procurement structure

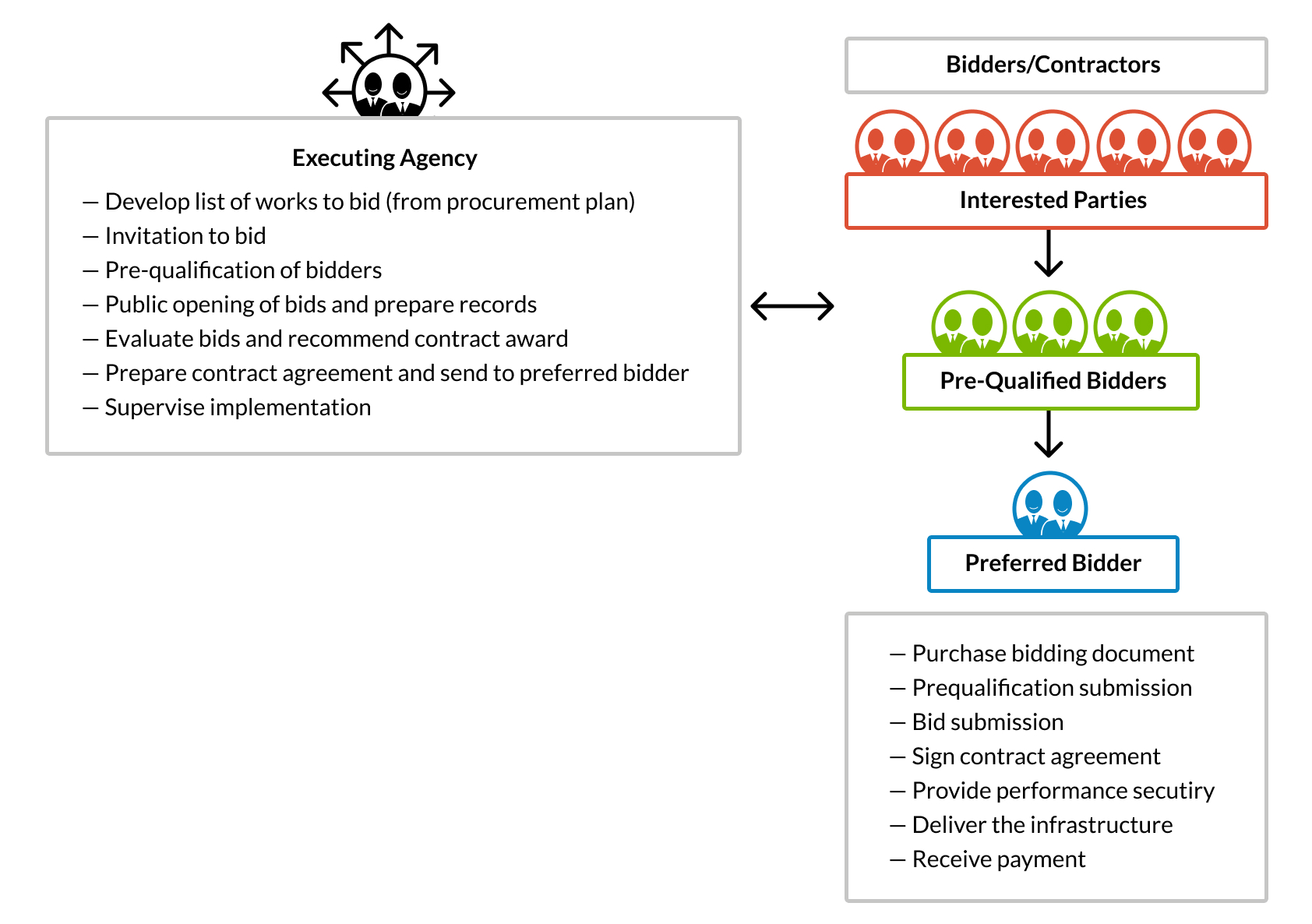

Having developed a TDP and completed project preparation activities, the government and the procuring entity need to identify a procurement approach. The government must decide earlier on which entity will manage procurement. Below we will briefly discuss different types of procurement that can be considered. The procurement approach, planning and structure are discussed in great detail in the Understanding Power Project Procurement handbook.

A procuring entity might use a variety of procurement processes. Broadly we use the categories described below as a framework for discussing the different processes.

Competitive tenders

A competitive tender (also called an auction or competitive bidding process) is a process initiated by a procuring entity to select the sponsors that will develop a project through a competitive process. A competitive tender requires investors to compete directly against each other, on the same terms, for the opportunity to develop a project (or projects). This procurement structure harnesses the power of competition to achieve the objectives of the procuring entity. Bids are therefore evaluated primarily on price, but may also include additional evaluation criteria.

Direct Negotiations

Negotiating a project with single or multiple developers without inviting other interested parties to engage in a procurement process is referred to as either a negotiated deal, a direct negotiation, or a sole-sourced power procurement. A direct negotiation may be initiated by the procuring entity or by the sponsors. In either case, the procuring entity must ensure that direct negotiations are permitted under applicable law while also considering the funder’s procurement requirements to ensure that the capital works gets funded.

Summary of Key Points

- All transmission projects start with planning.

- Governments and transmission utilities are best placed to conduct the planning across the sector. The reasons for this are efficiency, cost optimisation, cost-effectiveness and reliability.

- Stakeholder consultation during the planning process is recommended to produce a more implementable and robust plan.

- Integrated resource planning and transmission development planning provide a prioritised list of projects that can proceed for project preparation.

- Governments can access various donor funds to assist with the planning and project preparation activities.

- Private sector participation in these transmission projects can be procured via competitive processes and through direct negotiations. Competitive processes will be more compatible with DFI funding.