12

Regulatory Framework

Introduction

Regulatory frameworks are fundamental to the effective operations of the electricity sector in any country. A predictable regulatory framework is of particular importance to private funding structures since the existing framework forms the assumptions upon which the investment is made at the outset of the project and ongoing regulation represents a risk over the life of the project.

The elements that define a well-constructed and transparent framework include autonomy, consistency, and predictability. With these elements legislated and demonstrated in practice, it will be easier to attract funding of private business models and stimulate transmission infrastructure investment. Improving the regulatory framework for transmission projects will also benefit the market more broadly by incentivising efficiency and bringing down costs for consumers.

In addition to the general need for a well-developed regulatory framework, the introduction of private investment in the transmission sector will also require targeted changes to existing regulations to address barriers that may otherwise make private investment impossible.

In this chapter we will discuss the following:

- the characteristics of an independent regulator;

- how regulatory transparency can be achieved;

- economic, market, and licensing regulations; and

- reducing regulatory barriers to private investment.

Regulation by Contract

For certain private investments where the transmission project will operate largely on an independent basis (e.g., whole-of-network concessions and IPT models), it may be possible to finance a project even if the regulatory framework is not fully developed. Both the economic and technical regulations described in this chapter can be defined directly in the project agreements, which is referred to as Regulation by Contract. This does not foreclose the possibility of developing a regulatory framework as that legislative process may continue in parallel with the implementation of the project. There are many cases in the power sector where one or two projects have led the way and provided useful lessons learned that are translated into long-term regulations. It is important to note, however, that the use of Regulation by Contract should be limited as a widespread use would result in a market with widely divergent regulation of different projects. Any plan for wide-scale investment from the private sector will require an independent and stable regulatory framework that governs all market actors on equal terms.

Definition of an Independent Regulator

The independence of the regulator is a primary concern for transmission project investors given the significant possibility for political influence in the energy sector. As a regulated asset that supports the broader public benefit of energy access, there is often an incentive for political actors to artificially lower transmission and other energy costs to generate goodwill with consumers (particularly ahead of elections). In its basic ideal form, an independent regulator will not be subject to any political influences or special interest groups and will be autonomous in its governance of the energy sector. Some of the characteristics of an independent regulator are:

- an independent board that has a duty of care to all sector stakeholders;

- independent funding mechanism via licensing fees;

- resources and capacity to conduct regulatory activities (economic, technical, legal, and compliance functions) without the need for government or utility support; and

- legislation that allows for accountability to all stakeholders independent from the executive or legislative branches of government.

As a general rule, legislative frameworks that govern electricity sectors establish the regulator as a separate legal and independent entity outside the ministry that is responsible for energy. Although the government may establish policy objectives for the sector, the independent regulator is responsible for ensuring efficiency, transparency, and fairness in the management of the electricity sector and benefits from the discretion that is required to achieve those objectives and to balance the interests of investors and consumers. Among other things, the concepts of regulatory independence and discretion mean that a regulator is permitted by law to modify its tariff guidelines at any time, yet with a reform procedure that involves broad consultation with all participants, particularly sector stakeholders.

How Transparency Can Be Achieved

A transparent regulatory framework can create credibility for the regulator and the regulatory decisions it makes. Even when service providers are all public entities, stakeholders including the government, consumers, and utilities are more likely to express confidence in the regulator if its decisions are guided by clear rules, procedures, and methodologies and if stakeholders participate in the decision-making process.

Transparency makes it easier to attract private investment in financing through any of the available business models discussed in this handbook. This is because private investors are more likely to choose legal and regulatory frameworks in which their rights and obligations have been clearly defined and the decisions of the regulator are predictable.

Measures to achieve and enhance transparency in the regulatory framework include clarity of the rules and procedures of the regulator and the rights and obligations of regulated entities, the autonomy of the regulator, regulator accountability to stakeholders, predictability of regulatory decisions, broad stakeholder participation in the regulatory process, and open access to information about the process.

Clarity of roles, rights, and obligations

Regulatory transparency can be enhanced when the roles and objectives of the regulator are spelt out in primary legislation and other instruments such as contracts. The rights and obligations of the regulated entities also need to be clearly stated so that expectations are clear to all stakeholders. This feature of the regulatory framework is particularly important to private developers and their financiers.

Autonomy of the regulator

Good regulatory governance requires that the regulator is protected by law and in practice from interference from political actors, policymakers, and special interest groups. This may be achieved through various measures that ensure that regulators are not funded through government budgets or by the utilities, and balanced stakeholder representation on the board of the regulators.

Accountability to stakeholders

To avoid abuse or the perception of abuse of its autonomy, a good regulatory framework should create the framework for stakeholders to challenge the decisions of the regulator, and most importantly, to obtain redress when the decisions are not per the rules and procedures.

Predictability of regulatory decisions

In a good regulatory framework, the decisions of the regulator will be predictable. This means that regulatory decisions are made under established rules, methodologies, and processes. It calls for clearly spelling out in regulatory documents - including licenses and contracts- the factors that feed into the decisions of the regulator. These factors may include definitions of parameters such as the rate base, price adjustment formulas, and timetables of events.

Stakeholder participation

Broad stakeholder participation in the regulatory process enhances transparency and the legitimacy of the regulatory framework and bolsters consumer confidence that the regulatory system will protect them from unreasonably high prices or poor quality of service. Typical stakeholders will include regulated entities, non-regulated ones, consumers, policymakers, and other public authorities. These stakeholders should be encouraged to participate actively in the regulatory decision-making process, to provide regulators with as much information as possible about their views and about the impact that a regulatory decision would have on them.

Open access to information

Open access simply means that the laws, rules, processes, methodologies, and consultation papers that inform the decisions of the regulator and the decisions themselves are readily and openly available to stakeholders and the general public. This is one way to enhance the transparency of the regulatory framework and foster stakeholder participation and stakeholder confidence in the regulator and regulatory decisions.

Functions of a Regulator

Economic regulation

Economic regulation is needed in areas where no functional competition is possible. Electricity networks are a prime example of this lack of constitution since they typically constitute a natural monopoly and require regulation to limit monopoly pricing and to set incentives for efficient performance.

Economic regulation typically involves ensuring the financial sustainability of the utility through tariffs that are cost-reflective and incentives for the efficient cost of operations. It also allows for utilities to have returns that allow for future investments and still balances the requirements for affordability to ensure access for all. The necessity for economic regulation that balances the need to limit monopoly effects with the financial sustainability of the utility applies equally to both public and private transmission companies.

Methods for economic regulation

Some of the methods used for economic regulation by regulators include:

Rate of return (ROR) regulation: At the basic level this method allows the regulated entity to recover its justifiable prudent cost and is allowed a return on the regulated assets (or rate base). Under this method of regulation, regulators evaluate the firm's rate base, cost of capital, operating expenses, and overall depreciation to estimate the total revenue needed for the firm to fully cover its expenses. It makes room for clawbacks and claims for over- and under-recovery of cost, typically through clearing accounts. It should be noted that in some jurisdictions the term cost of service regulation, or COSR, is used. The most commonly used term in Africa, however, is RoR.

Incentive-based regulation: This method determines the revenue requirement for the transmission utility using a future period called a control period. The control period is a long interval between tariff reviews, usually 4 or 5 years, within which the revenue requirement is frozen. In the control period, tariffs are allowed to increase at a rate that comprises the difference between the country’s annual consumer price index (CPI) or inflation rate and a productivity factor. The goal of this method is to ensure that at the end of the control period, the transmission utility’s allowed revenues equate to its costs, and efficiency gains are passed on to the consumers in the next control period.

This model can take either of two approaches: the price cap and the revenue cap approaches.

Price cap regulation: Sometimes referred to as CPI-X, this method attempts to adjust the utilities’ prices according to the price cap index that reflects the overall rate of inflation in the economy, the ability of the operator to gain efficiencies relative to the inflation in the utilities input prices, relative to the average in the economy.

Revenue cap regulation: This method allows the utility to change its prices as long as its revenue remains below the cap set.

The effective application of these methods will lead to a predictable methodology for calculating the economic return for transmission projects and make it easier for potential investors to assess the commercial viability of any given project.

Cost recovery: transmission tariff considerations

Efficient regulation will be required to determine the price (cost) of transmission through a transmission tariff that will be ultimately borne by the electricity end user. The transmission tariff will be designed using principles that enable fair allocation of the cost of transmission between generation and consumption, reduce the investor’s risk of cost recovery, incentivise network users to make the best decisions on the location of new generation and load, and reduce system operating costs.

When the transmission costs are clear and fairly allocated, it becomes easier to attract financing through any of the available business models discussed in this handbook.

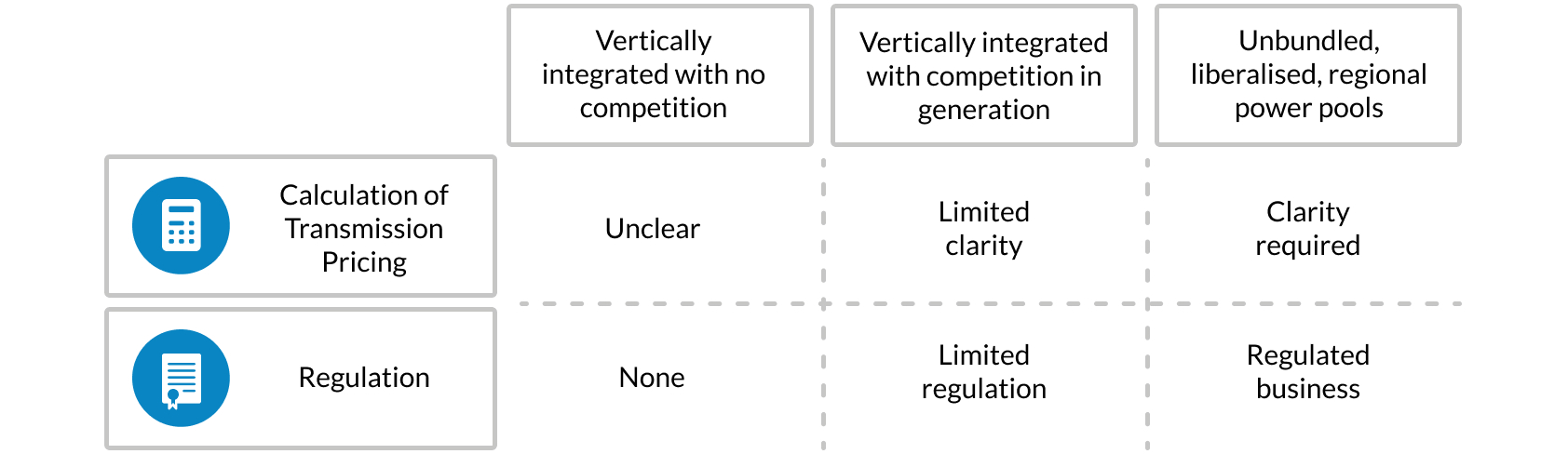

To attract financing for transmission, governments will have to consider how their respective electricity market structures affect the transparency of their transmission costs. The regulatory tariff models and pricing methodology used in Sub-Saharan Africa to calculate the upstream costs of transmission depend largely on the structure of the electricity market. Thus, vertically integrated electricity markets with little or no unbundling or competition differ in their approach to transmission pricing from unbundled markets with a partial or full competition. This impact of the market structure on transmission pricing affects the extent of regulation for and transparency in the cost of transmission.

In vertically integrated monopolies with no market competition, the costs associated with transmission are often unclear. While it may be possible to determine the fixed costs of new transmission lines, the variable costs of operating and maintaining the grid may not be easily separated from the operation and maintenance costs for associated generation plants and the distribution system. Corporate and administrative costs also remain bundled.

Further, limited regulation of transmission pricing is seen in most countries that have introduced competition in generation while retaining a vertically integrated monopoly structure. The regulator ensures that the connection charges for a new generator — typically an IPP — cover the costs of constructing, operating, and maintaining the network facilities that are strictly required to connect the IPP to the monopoly’s network. However, the costs related to the use of the system by both the generators and the utility are not clear. Thus, proper cost allocation may not be feasible under current tariff structures in markets with vertically integrated utilities and new regulations may be needed to establish a predictable methodology for transmission pricing.

Transmission pricing is clearer in some countries that have undergone full legal unbundling: separation of generation, transmission, and distribution functions into different legal entities. The laws in such countries also establish independent regulators that create regulatory frameworks to allocate the benefits and costs of using the transmission network among the various participants in the market and recover the costs of investment. Yet, the degree of transmission cost transparency in such markets depends on the extent of the regulator’s independence and its ability to design and implement cost-reflective tariffs.

Nonetheless, all countries regardless of market structure can regulate and achieve transparency in transmission costs. Costs of transmission in vertically integrated monopolies can be regulated and be transparent without a full legal unbundling exercise. This is possible if the existing monopoly utility is required to maintain separate accounts for the various services it renders (generation, transmission, distribution) which are then monitored by an independent regulator. This introduces transparency and predictability without the need to fully unbundle the legacy utility in a market.

Case Study — Mauritius

The legal and regulatory framework established by the Mauritius Electricity Act, 2005 (as amended, 2020) contemplates the existence of an independent regulator (the Utility Regulatory Authority) and a requirement that a licensee who provides more than one electricity service should keep separate accounts and publish separate financial statements for each electricity service. Hence, the vertically integrated utility will keep separate accounts for generation, transmission, and distribution. Such practice — known as accounting unbundling — can enable a vertically integrated utility to avoid cross-subsidisation of costs among its respective businesses, determine the true cost of transmission, and publicly disclose such costs. The regulator is also better equipped to properly allocate transmission costs to other network users such as IPPs and bulk purchasers.

Market Regulations and Compliance

An electricity regulator also performs in some markets the function of a market regulator in addition to the economic regulations. This includes for the transmission business the development of the grid codes that govern the technical specifications and performance requirements. Adherence to this is usually specified in the licence.

A regulator also plays an important role in monitoring compliance to licensing conditions and other legislation. To do this effectively, the regulator will need to be appropriately resourced and have the necessary legislative powers to impose sanctions for infringements.

As electricity markets become more liberalised, the functions of the regulator will need to be reinforced. With a multitude of stakeholders and consultants being a foundation of regulatory processes, the regulator’s ability and resources to undertake these activities need continual focus. A regulator without the resources can quickly lose its independence, even if in some instances this is not total independence.

Licensing

Another function that a regulator performs is to issue licenses. Some of these licenses, permits, and consents apply to virtually any type of business. A business license may be required by the localities in which a business owns property, operates, or has an office, for example. Planning, location, and construction permits are likely to be required to construct transmission facilities, substations, offices, and other facilities. At the other end of the spectrum, some licenses, permits, and consents are specific to the power sector, and to transmission in particular. A transmission license is a good example of a license that is specific to the transmission sector.

The transmission license typically authorises the holder to own, construct, and operate physical installations for transporting electricity from a production point to a consumption point, either within the country or outside the country. In many African countries, cross-border transactions will not fall under the remit of the local countries’ regulator and may be regarded as an unregulated business.

The system operation license authorises the holder to engage in activities that ensure the reliability of the entire network. Thus, the system operation licensee will manage electricity flows on the network, and undertake non-discriminatory generation scheduling, commitment and dispatch, transmission congestion management, transmission outage coordination, system planning for long-term capacity, and procurement and scheduling of ancillary services. The system operator does not own or operate physical transmission facilities and has no financial interest in the electricity flow on the transmission lines.

Regulatory Implications for the Private Sector

This section will discuss the regulatory framework required to attract private investments in transmission. While the bulk of private investment in power infrastructure is directed to generation projects, governments and regulators are increasingly moving towards the introduction of private participation into other segments of the power market, such as transmission and distribution. Even with private participation, the need to maintain the stability and accessibility of power markets remains. Regardless of the mix of public and private participation in the power market, a regulatory framework that establishes market rules, prohibits and provides protection is an important focus for governments and regulators.

Removing entry barriers to private investments

Since electricity transmission infrastructure has traditionally been managed as a public asset, the regulatory framework must often be adjusted to specifically authorise private participants to undertake grid activities. Grid activities include planning for transmission projects, construction of new transmission infrastructure, maintenance planning, and system operation. Some jurisdictions divide these activities into two licenses which may be held by the same entity — a transmission license and a system operation license.

If a country’s legal and regulatory framework contemplates that only the state-owned utility will perform the activities listed above as strictly “transmission license” activities, it will be difficult to attract private investments into the transmission segment of the electricity supply chain. The business models discussed in this book are only possible if the electricity laws and regulations are drafted to allow private entities to hold “transmission licenses''. These licensees can coexist with state-owned utilities who may also provide transmission and/or system operator functions. However, the licensing regime must ensure that private entities which undertake strictly transmission activities allow non-discriminatory connection to the installations they own and operate. The licensing framework should also clearly establish the steps for obtaining a transmission license and the costs involved.

Secured interests in transmission assets

One significant change in the regulatory framework for transmission systems that must be anticipated with the introduction of private investment is the need for investors to obtain a secured interest in any transmission assets that are covered by a license, concession, or any other business model. This may be a significant departure from existing frameworks that assume transmission assets are to be held by a public entity on behalf of the state. The form of secured interest that investors require may vary significantly, based upon both the project structure and the type of financing. In general, however, the regulatory framework should anticipate the need to grant interests to private parties in the physical assets (land, equipment, etc), legal assets (operating license, sales/marketing agreements, etc), and financial assets (tariff payments, receivables, etc). Without this security, the investor will be unable to demonstrate to their shareholders or lenders the financial security necessary to fully fund the project's development and the cost recovery potential.

Currency risk

As discussed later in this book within the context of financing, privately financed transmission projects often require that the investor borrow funds in either local currency or reserve currency. The local currency is the currency of the jurisdiction in which the project is to be constructed and operated, and reserve currency is a currency held in significant quantities as part of governments’ or institutions’ foreign exchange reserves. Reserve currencies, such as U.S. dollars and Euros, are commonly used in power and infrastructure transactions. As a result, any regulatory framework that intends to attract private investment in transmission infrastructure must also authorise the payment of transmission tariffs in either local or reserve currencies (or possibly a combination of both) to ensure that the private financing terms of the project are compatible with the publicly regulated payment structure. For additional detail on currency risk in private projects, see chapter 11. Common Risks.

Dispute resolution

With the introduction of private participation in the transmission segment of a domestic power market, it is often necessary for the regulatory framework to accommodate the need for alternative forms of dispute resolution to quickly and fairly resolve any issues that arise at the contract or operational level. For example, as new technologies and operational standards are introduced by private parties, the regulatory framework may authorise the appointment of independent engineers to help reconcile any conflicts between legacy and modern systems. Similarly, if a major dispute were to arise between public and private parties, it would be expected that a neutral dispute resolution system, such as commercial arbitration, could be utilised to resolve the dispute, an option that would need to be specifically authorised in the regulatory framework (public entities may also be required to waive their sovereign immunity protections to enable the enforcement of any arbitration awards). For additional detail on dispute resolution, see chapter 11. Common Risks.

Summary of Key Points

- An effective regulatory framework for both public and private transmission projects should be transparent, consistent, and predictable.

- An independent regulator is critical and should not be subject to any political influences or special interest groups to facilitate autonomous governance of the market.

- Energy regulators provide vital functions for the sector such as economic and market regulation, licensing, and compliance.

- In addition to the general need for an effective regulatory framework, private projects will require specific regulations to protect investors.

- In limited cases, a private project may be negotiated in a market that lacks a clear regulatory framework through Regulation by Contract.

Deep Dive into Transmission Pricing

As explained in this chapter 12. Regulatory Framework, one of the primary functions of an independent regulator is to establish the pricing that the transmission utilities, be they private or public, can charge to generate revenue. This revenue will then cover the transmission utility’s costs, namely, the network investment costs (including a specified return on the capital deployed), operation and maintenance costs, ancillary service charges, and administrative costs.

This section of the book presents a summary of the most common methodologies utilised by independent regulators to establish transmission pricing. While any application of a pricing model will require careful study, economic modelling, and significant consultation with all market stakeholders, this section should provide a helpful overview of the diversity of pricing strategies available to regulators.

This section is especially relevant for the whole-of-grid concession funding structure as the pricing of the transmission charge by the regulator will be critical for the successful implementation of the business model. Note, however, that the level of technicality of this subject matter is high and goes slightly beyond the original intent of this book.

Tariff Setting Process

The basis for determining the transmission utility’s allowed revenues depends on the tariff model adopted by the regulator. As detailed in this chapter, there is a range of tariff models that may be deployed by the regulator. However, before investigating each model, it is important to note that any uncertainty in the process adopted for tariff making is itself considered a risk for private investors.

A key feature of the revenue models for private transmission projects is the periodic regulatory review of the tariffs. At the outset of a project, the tariff will be established, based upon the allocation of existing assets to the private operator (in a privatisation or concession model). However, over the life of the project, as the need for additional investments in the transmission network/segment are identified, the regulated tariff will need to be reviewed. Additionally, between reviews, the existing regulated tariff may be allowed to increase by an escalation factor that reflects inflation or other changes in economic growth. The investment agreement may also include key performance targets for the private transmission project, which may also be adjusted over time as the assumptions underlying those performance targets evolve with appropriate rewards or penalties attached to the performance targets.

Given the significant need to treat tariff setting as an ongoing exercise rather than a one-time event, it is critically important for the regulator to communicate to the market how it plans to engage in this process and invite feedback to build trust in that process. Some areas of concern include: the model applied in the valuation of the transmission assets, the establishment of a reasonable return on invested capital, and the characterisation of the nature of new assets that are included in the regulated asset base.

Tariff Methodologies

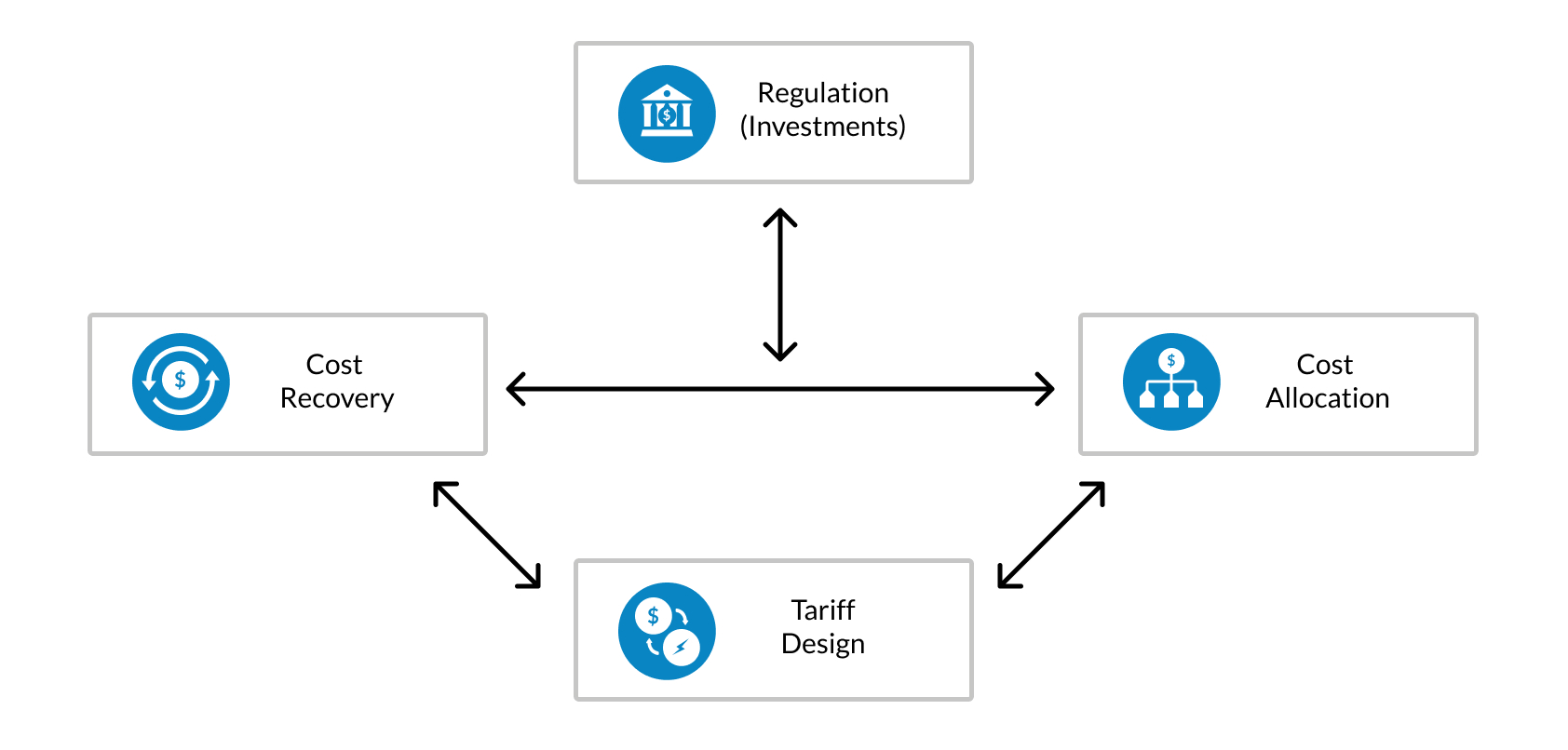

In general, the process for transmission tariff design is divided into three phases:

- Establishing the allowed costs (annual revenue requirement) of the transmission utility through any of the revenue regulation models for network monopolies.

- Deciding how the transmission utility’s revenue requirement will be allocated among network users in the form of connection and use-of-system charges.

- Designing the format of the charges.

The methods for establishing the allowed costs have been briefly described in the main chapter ‘Regulatory Framework’. These include the cost of service model and the performance-based regulation model. However, the various considerations and calculations in these models are not discussed in detail in this book.

After determining the transmission utility’s costs or revenue requirement, the regulator allocates these costs among network users through transmission charges. Transmission charges can be broadly divided into two categories:

- the connection charge; and

- the transmission-use-of-system (TUOS) charge.

Connection charges

Connection charges are designed to recover the transmission utility’s costs for constructing and maintaining the connections and associated transformers required by individual generators and wholesale buyers. Regulators typically take various approaches to recover the connection costs. These approaches depend on whether new facilities are needed to connect the network user and the extent to which the new connection facilities will benefit other users of the transmission network.

If new facilities are not needed, then there is typically no network charge. However, if new facilities are needed, whether the connection charge will be separated from the TUOS charge depends on whether the connection costs are shallow or deep.

Shallow connection costs cover the cost of new facilities dedicated to connecting a network user to the grid. The connection charge allowed by the regulator will cover the cost of the meter, any transmission substation, and the cost of the usually short line between the network users and the transmission utility’s network. The regulator may decide to levy those charges to be paid upfront or to spread the payments as monthly costs over time. Such costs may also be shared among all users connected to that specific node in the transmission network.

Deep connection costs cover facilities that benefit existing network users or future network users. For instance, system upgrades or reinforcements may be necessary because the network is congested at a certain connection point. New lines and associated transformers may also be needed when there is a long distance between the new IPP, distribution company, or industrial consumer and the preferable network connection point. In this case, the new facilities may be deemed part of the transmission network instead of a connection. Regulators typically include deep connection costs as part of the TUOS charge.

TUOS charge

Since the TUOS charge covers the cost of network investments other than shallow connection costs, operation and maintenance of the network, and the corporate and administrative costs of running the transmission business, the TUOS is the main transmission charge which the regulator must determine how to allocate among network users.

In allocating the cost of the network, the regulator aims to ensure that the method used is simple and transparent, non-discriminatory, fair, enables recovery of the cost from both present and future users of the network, and sends proper location signals to users in the network. There are various approaches used globally by regulators or suggested by academics for transmission cost allocation, and no approach is foolproof. Some of the common approaches used are postage stamp, wheeling, and distance-based methods.

- Postage stamp method: this is the simplest and most common method of transmission cost allocation. Using this method, the regulator allocates the TUOS costs among all network users through a uniform charge that applies regardless of the location of the user or the transactions involved. Thus, every generator and/or distributor receives the same charge per MW or MWh injected into the system, or per hour of the availability of the transmission network. In some countries, the regulator divides the charge into proportions between generators and distributors/bulk purchasers. Hence, generators may be responsible for a certain percentage (say 60%) of the TUOS charge divided among all generators uniformly, while the remaining percentage is shared uniformly among distributors/bulk purchasers. In Nigeria, the postage stamp method is used to apply uniform TUOS charges only to distributors/retailers.

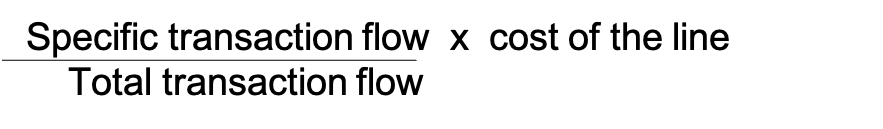

-

Wheeling charge method: this method is based mainly on

the transactions between two users and is commonly used in bilateral

electricity trade between two countries. It involves

the determination of a fictional transmission path, by parties

to a power sale transaction, in which the electric flow will

pass from the point of injection by the seller to the point

of delivery by the buyer. The charge is computed as

a fraction of the cost of the network path (lines and associated

infrastructure) where the transaction “flows”. In a very

simplified form of applying this method, the regulator computes

the cost of respective lines in the network and

the estimated total annual flow on these lines. The wheeling

charge is then simply expressed as:

-

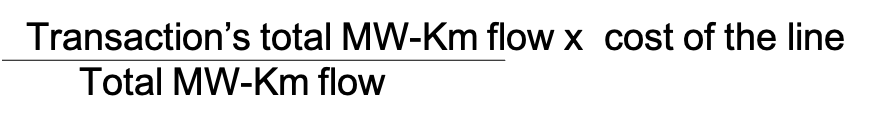

Distance-based method: this transaction-based method considers not

only the amount of energy transmitted through the line but

the length of each line used for any transaction. In a very

simplified form of applying this method, the regulator develops

a base case scenario in which it:

- Identifies all transactions using the network;

- Determines the fictional transmission path for each transaction;

- Determines the transmission flow in MW per transaction per line;

- Multiplies the transmission flow per transaction per line by the length of the line to get an MW-km product;

- Sums all the MW-km products for all transactions using the line to arrive at a total MW-km base case amount.

Then, removing any particular transaction, the regulator repeats the above process and calculates the resulting total MW-km amount. The difference between the second sum and the first sum is the amount of MW-km flow on the line allocated to the transaction removed. The transmission charge is then calculated as:

Nodal pricing

In some liberalised or wholesale electricity markets, the cost allocation methods described above are used to determine fixed charges that supplement other charges known as variable network charges. The variable network charges are implicit charges derived from the differences in marginal prices among different nodes in the electricity network. Such differences exist in a market system as a result of losses in the transmission system. Nodal prices are used to send signals to network users on more efficient locations to site new generation or load.

When electricity is transmitted from one point (node) to another, some of the electrical power is lost as heat. The amount of power lost depends on the distance of the generator to the load (the farther the distance the more power is lost), the resistance of the transmission lines, the environmental conditions, and the amount of power flowing through a line at any particular point among other factors.

Using a model that calculates the impact of each user on the transmission losses, each generator’s marginal costs, the demand level at each node, and active transmission constraints, the regulator assigns loss factors or node factors to various nodes in the system. These factors are used to determine the electricity prices at each node. The loss factor estimates the losses associated with injecting or receiving an additional unit of electricity at any particular node. It is also used to calculate the marginal cost of meeting electricity demand at any node. For instance, if the loss factor at a particular bulk supply node is 5% and a generator has a contract to deliver 100 MW to that node within an hour, the generator must supply 105 MW to meet its delivery contract to the node and the associated losses. Thus, if there is a bulk supply connected to the generator’s node, the marginal cost of meeting demand at the generator’s node will be less than the marginal cost of meeting demand at the other bulk supply node — there will be fewer or insignificant losses at the generator’s node.

The differences between the prices of electricity between nodes are allocated to the transmission utility as variable network charges. Because these charges are variable and depend on a lot of contingencies, they may be insufficient to recover the investment and operation costs of the transmission utility. Hence, the regulator uses the cost allocation methods previously described to determine supplementary charges for the transmission utility.

In countries that do not use wholesale electricity prices, and electricity generation prices are not determined by market forces, the regulator may use transmission loss or congestion factors as an alternative to achieve the same locational signal objective associated with the use of nodal prices. With this practice, the generator bears the cost of the extra units of electricity needed to cover the transmission losses related to its generation. This practice is used with the fixed cost allocation methods (supplementary charges) discussed previously.

Designing the transmission tariff structure

After determining the method for allocating the costs among network users as fixed or supplementary charges, the regulator finally determines the format of the tariff. The regulator’s decision on tariff structure may affect the private investment decisions and deserves careful consideration. The regulator may decide to design the transmission tariff as a lump sum, a volumetric energy charge ($/MWh), a volumetric capacity charge ($/MW), or an hourly availability charge ($/hour of t-line availability). As a lump sum charge, the regulator designs the TUOS cost allocated to a user as a one-off charge to be paid by the user annually. The regulator may also divide this lump sum into fixed monthly charges.

As an energy charge, the recovery of cost by the transmission utility depends on the actual energy generated or consumed by the network user. This may expose the transmission utility to losses since it has no control over the behaviour of other network users. For instance, with the increase in behind-the-meter installations, an energy charge for transmission means that network users whose demand may have justified transmission investments will avoid payments for such transmission infrastructure in their end-use tariffs. This may affect the transmission utility’s ability to pay costs associated with private investments in the transmission network. There may also be fairness issues associated with the other tariff formats which are structured as capacity charges or availability charges. Some network users may feel that they are paying more than other users if their electricity production or consumption rates are considered.

Some regulators balance these considerations by using a mix of energy charges and capacity or availability charges. The suitable tariff format or a mix of formats adopted by the regulator depends on the nature of the market, the business models for private investment in transmission allowed in the market, and the regulatory goals. Nonetheless, the tariff format should ensure that the transmission utility recovers its cost without compromising on principles of fairness, non-discrimination, and transparency.